This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Extreme water events affecting water for drinking, cooking, washing and agriculture drive migration all over the world. Earlier this year, cyclone Eloise battered Mozambique, displacing 100,000 to 400,000 people and weakening the country’s infrastructure. People displaced by the storm were in need of food, hygiene kits and personal protective equipment (PPE).

Cyclones are just one form of extreme water events that will play out more frequently and adversely as water crises worsen with climate change. Water extremes and climate change will cause more than one billion people to migrate by 2050.

Migration will be spurred by drought, as in the Sahel in Africa, shortsighted water management, as in the Aral Sea region of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, flooding, as in Bangladesh and small island developing states, and other extremes like cyclones.

Addressing water-driven migration will require research that crosses borders and research boundaries. As climate change continues to cause serious displacement and socio-political upheaval, governments must take action to minimize the effects on people vulnerable to migration.

The stakes of water-driven migration

Water-driven migration is a crucial challenge for people living in vulnerable and unstable regions. Water stress acts as a direct or indirect driver of conflict and migration. As water and climate extremes become worse, more people will face water crises and be forced to migrate.

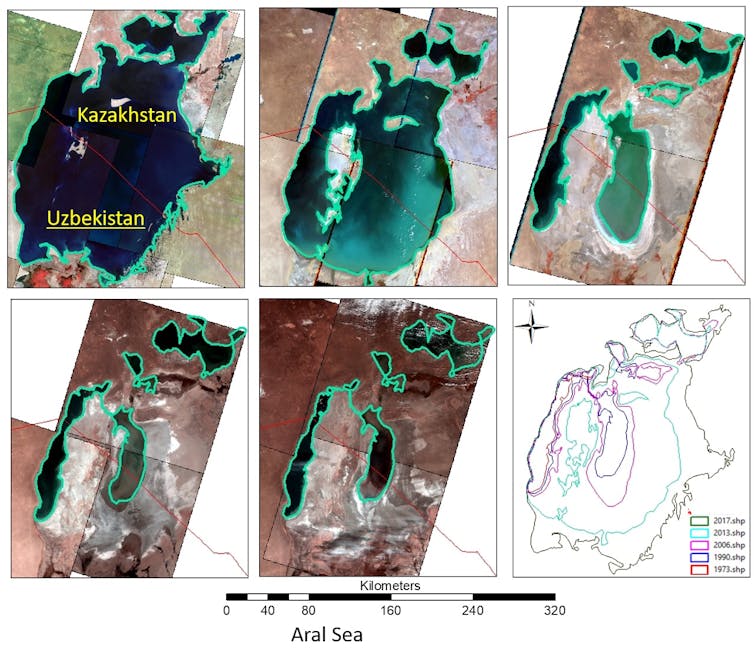

For instance, take the famous case of the Aral Sea that shrank to 9,830 square kilometres in 2017 from 55,700 square kilometres in the 1970s. More than 100,000 people migrated due to collapse of agriculture, fisheries, tourism and increased illnesses such as tuberculosis and diarrhea.

(Landsat data mapped by UNU-INWEH), Author provided

Vulnerable populations bear the brunt of impacts on water availability, food production, livelihoods and income. As water and care providers, women and girls carry the burden of fulfilling water needs for their households and families. Women and girls also bear disproportionate health impacts of water crises as more hours are spent organizing household water needs.

A recent report explains that political instability, chronic poverty and inequality and climate change worsen water-driven migration. With at least 33 nations set to face “extremely high (water) stress” by 2040, it is more pressing than ever to face this problem with a strategic approach.

A seven-point strategy

Countries that have committed to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals could address water-driven migration through SDG 16 (peace, justice and strong institutions). Policy can be aligned with SDG 16 along a seven-point strategy:

- Address the connection between water ownership, distribution and migration: Water ownership and distribution likely influence migration at local, regional and global levels. To capture the scope of water issues, future research must strike a balance between scientific and social aspects of water.

- Understand how water crises influence migration: Causality is important in addressing migration. Land, water and human security issues could serve as a base for outlining a preventative outlook for new and emerging migration pathways.

- Integrate diverse perspectives in water migration assessments: Water co-operation treaties must integrate under-represented, marginalized and racialized migrant voices. The United Nations University’s Institute for Water, Environment and Health has developed an approach to aggregate the causes and consequences of water-driven migration. This framework can help policy-makers interpret migration in diverse socio-ecological, socio-economic, and socio-political settings.

- Assess water, migration and development practices through participatory, bottom-up and interdisciplinary approaches: Research should be participatory, applicable between disciplines and socially inclusive to complement scientific, descriptive methods. Nuanced facts of the diverse influences that shape migration can provide understanding to build resilience among vulnerable populations.

- Manage data, information and knowledge: Researchers need updated data to examine how water crises are linked with human migration. To close the gaps, the UN has pointed to the need to improve capacity for data analysis within and between countries. Also, there must be stronger co-ordination at the state, regional and international levels to share best practices.

- Apply a gender-sensitive lens: The economic, health and societal effects of water-driven migration affect men, women and children differently. Filling these knowledge gaps will require a gender-sensitive approach to assess causes and effects. Namrata Chindarkar, a water and public policy researcher, has argued that comprehensive and holistic investigations of the states people come from, end up in and transit through must be gender-sensitive if they are to be inclusive.

- Understand water, migration and peace: There is potential for using water security to promote peace. Broader approaches could help examine key links between water, migration and peace.

Policy-makers must prepare for the consequences of water crises by adopting improvements that address the concerns of those vulnerable to migration. The seven-point strategy calls for policy-makers to use strategic and integrated approaches between disciplines. Research that maps causes, risks and impacts at the local, regional and global levels can strengthen water migration policies.![]()

Cameron Fioret, PhD candidate, Department of Philosophy and Prof. Nidhi Nagabhatla, School of Geography & Earth Sciences and Research Fellow (UNU-CRIS), McMaster University