The mental health of farmers is worse than it was five years ago and worse than that of the general population in almost every way, finds a new survey from University of Guelph researchers.

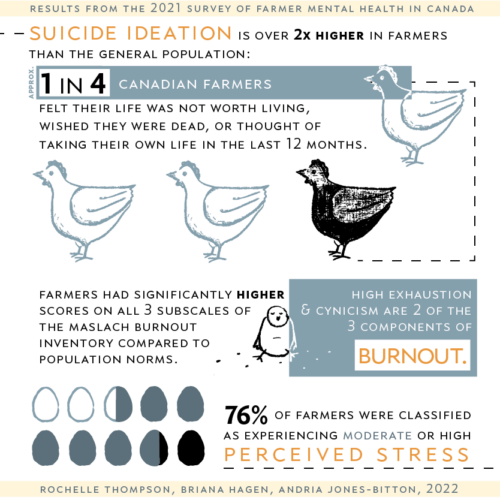

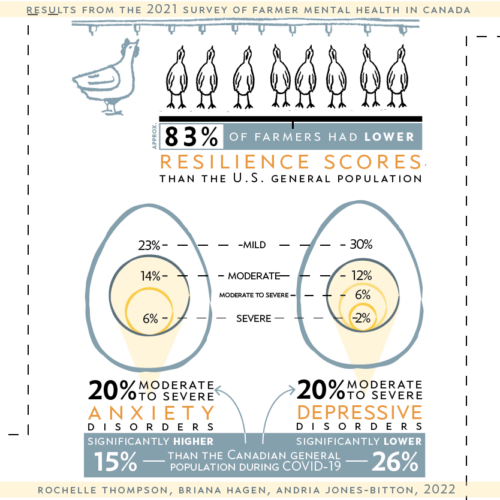

Stress, anxiety, depression, emotional exhaustion and cynicism (two components of burnout), suicide ideation and lowered resilience were all higher among farmers than the national average, found the team. The research was led by Dr. Andria Jones-Bitton, a professor in the Department of Population Medicine at the Ontario Veterinary College who has long studied the mental health of farmers.

Jones-Bitton, along with post-doctoral researcher Dr. Briana Hagen and master of science student Rochelle Thompson, analyzed the responses of nearly 1,200 Canadian farmers who completed an online version of the Survey of Farmer Mental Health in Canada between February and May 2021.

The research team found that 76 per cent of farmers said they were currently experiencing moderate or high perceived stress.

Many respondents also reported they had been thinking about suicide. Suicide ideation was twice as high in farmers compared to the general population. Additionally, one of four farmers surveyed reported their life was not worth living, wished they were dead or had thought of taking their own life during the past 12 months.

“Some participants left comments to illustrate the stress they were feeling,” said Jones-Bitton.

“One said, ‘There is no sick note for farmers. You don’t get paid if you can’t work,’ while another said, ‘The lack of control is very frustrating – lack of control with respect to the weather, input costs and commodity prices are all very stressful.’”

Others mentioned rising fertilizer and fuel prices as well as supply chain shortages of equipment and parts as added stressors.

Pandemic added further stressors

“It’s a troubling situation,” said Jones-Bitton. “Farmers have long faced occupational stressors due to the weather, their workload and finances. The pandemic, however, added new stresses such as increased costs, reduced seasonal agricultural farm workers due to travel bans in 2020, and farm processing backlogs due to workers and trucker drivers being ill with COVID-19.”

The survey was conducted just as the second wave of COVID-19 was under way. This was a time when stress, burnout, anxiety and depression were high across all of society.

“Where participants had moderate to high stress, depression, anxiety and burnout scores, they reported the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated their symptoms,” said Thompson.

This is the second time Jones-Bitton and her team have surveyed the mental health of Canadian farmers. The first survey, in 2015-16, also noted higher than national average levels of stress and other mental health issues in farmers.

Women reported worse mental health than men

The 2021 survey found that stress and other mental health problems were higher among women in every aspect except alcohol use. Women also reported worse mental health in the 2015-16 survey, but the differences seem more pronounced in the latest survey, said the research team.

Much of the stress among women is connected to what Jones-Britton calls “role conflict,” whereby women often have on-farm and potentially off-farm responsibilities as well as other roles like household operations and being the “default parent” and go-to person for support.

Among those farmers who reported moderate to severe or hazardous alcohol use, the majority said their consumption had increased significantly since the start of the pandemic.

“This, in addition to the pressures of farming and the pandemic, places a large burden on women farmers,” said Jones-Britton.

While many farmers used active coping techniques to manage their stress, Hagen said many reported other problematic behaviours, including social withdrawal, sleeping more, changed eating patterns, using alcohol and self-blame.

“These avoidant coping behaviours can set farmers up for other issues down the road,” added Hagen.

‘Farming can be an isolating occupation’

Researchers say their study, which will be published soon, highlights the need for stress-management training and mental health programming to better support Canadian farmers’ resilience. They also say it confirms the need for evidence-based, coordinated research on mental health among Canadian farmers.

“The more we learn from research, the more we can understand the problems and possible ways to address them,” said Jones-Bitton.

The research team calls for better support of women in farming, who often have their identities as farmers challenged and have traditionally not enjoyed some of the leadership positions in agriculture. “We encourage men in farming to ask themselves, and discuss with each other, what they can do to better support and promote women in agriculture,” said Hagen.

Recent research by Jones-Bitton and Hagen found that a lack of accessibility to mental health supports and services, mental health stigma in the agricultural community and a lack of anonymity were among the main reasons that farmers do not seek the support they need.

Thompson, herself a co-operator of her family’s century-old chicken farm, said she hopes this research will help bring attention and much-needed resources to address mental health in Canadian agriculture.

“Farming can be an isolating occupation and farmers with poor mental health need to know they are not alone,” she said.

Jones-Bitton and her team are currently analyzing the data for risk factors and are preparing to publish the full findings of their survey, which was funded by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. They plan to update the survey findings every five years.

Contact:

Dr. Andria Jones-Bitton

aqjones@uoguelph.ca