Long before the University of Guelph’s Arboretum came into being, Attawandaron, Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee and other Indigenous peoples lived on the land it occupies.

Now, numerous initiatives are under way to ensure that Indigenous knowledge systems are integral to the life of this significant green space in teaching, research and outreach.

“We are walking step by step on a variety of efforts across the arboretum, braiding Western and Indigenous ways of knowing and understanding,” said arboretum director Justine Richardson. “We are working with different Indigenous researchers, teachers, students and community members on a number of exciting initiatives.”

In its land acknowledgement, the arboretum recognizes that it sits on the Between the Lakes treaty territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit. It embraces the fundamental teaching of the Dish with One Spoon covenant — that there is one earth we all must equitably share and protect, said Richardson.

As Indigenous science increasingly contributes to the understanding of the animals, gardens, trails, meadows and woodlands of the 162-hectare (400-acre) arboretum, Richardson said, steps toward reconciliation are taking place.

Several current initiatives bring Indigenous perspectives to the space and aid in that process, she added.

“As a land-based hub that is a core part of the University of Guelph’s identity, the arboretum is in so many ways an appropriate spot for reconciliation efforts to happen.”

With guidance from Cara Wehkamp, U of G special adviser to the president on Indigenous initiatives, the arboretum began a process to understand better how scientific ways of knowing intersect with Indigenous ways of knowing, Richardson said.

“We are grateful to the Indigenous researchers, students and community members and organizations who are partnering with us in this learning journey.”

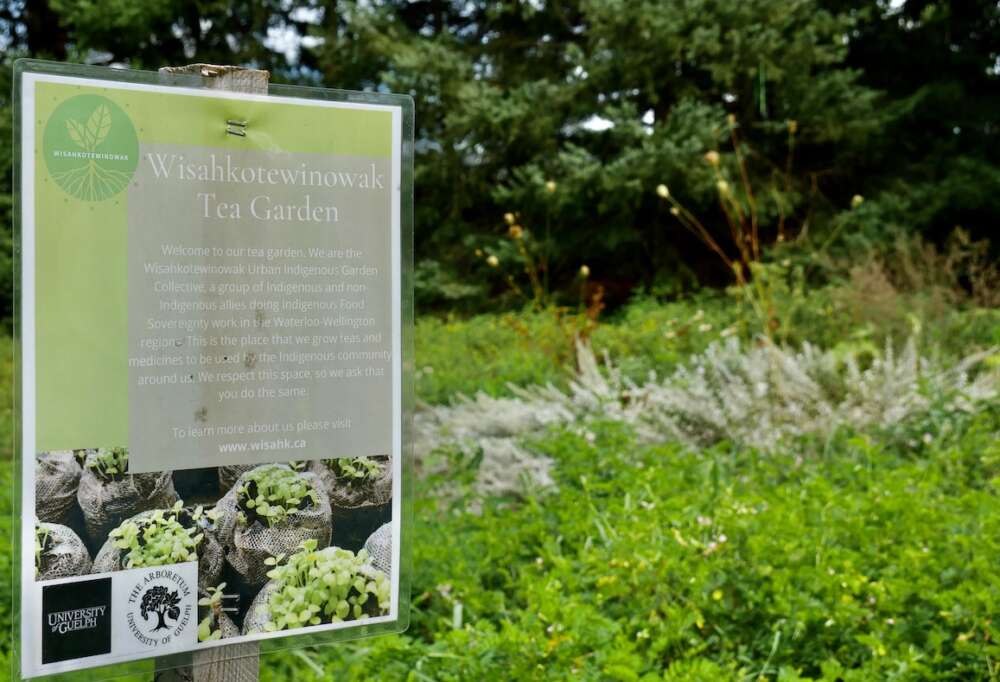

One recent addition to the arboretum is the Wisahkotewinowak Tea Garden. Located near the Gosling Wildlife Gardens by the Nature Centre, it is sown and maintained by the Indigenous-led organization Wisahkotewinowak, an urban Indigenous garden collective that fosters land-based relationships across the Grand River Territory.

The garden is planted with a variety of medicinal and herbal perennials used in Indigenous medicine, including sage, mountain mint, pearly everlasting, motherwort and bee balm. Workshops and community-engaged learning projects for Indigenous and non-Indigenous students on campus and beyond help to share knowledge of the plants and their properties.

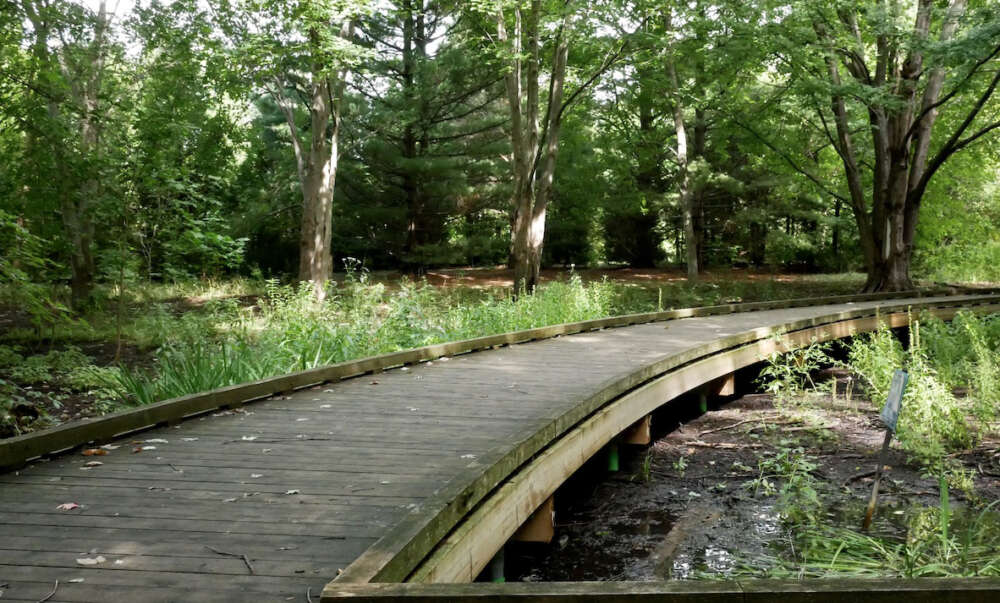

An area along the Memorial Forest boardwalk is now the site of one of the arboretum’s native plant restoration projects. Richardson said the site represents one step toward bringing back plants that once flourished here and reflects Indigenous ways of caring for and conserving the land and local plants, such as the deep red cardinal flower.

“Our work is exploring the question of how Western science and Indigenous science come together,” she said. “How do they connect to support biodiversity and address the urgent need for conservation in the face of climate change? And where do we need to adapt approaches, to attain a healthy environment and shared future?”

Another initiative is a project led by U of G environmental science graduate student Brad Howie, a member of Nipissing First Nation, who is helping to weave Anishinaabe knowledge, science, culture and language in the arboretum’s Victoria Woods.

His project, Mtigwaaki ‘Among the Trees’: A Journey in Anishinaabe Learning in the Arboretum, involves a series of signs about Anishnaabe understanding of the forest environment. Howie recently led an interpretive walk to introduce the sign project and he plans to do others.

The signs ask questions from an Anishinaabe perspective that understands humans to be one among many beings within the forest – a part of the forest, not a visitor to it.

The signs to be erected this fall will encourage reflection, asking questions about our place in the forest. How does one enter the forest environment? How are we related to creation? What does the forest give and what can we give to it? And how can we take action to treat Mother Earth better?

“The signs are meant to be universal,” Howie said. “It doesn’t matter where you come from in the world or what your religion is. The signs speak to everyone. What I really tried to do was develop a story. In Anishinaabe culture, storytelling is a cornerstone of the culture.”

Howie is also designing a new biodiversity identification sheet about insects from an Anishinaabe science perspective. It’s part of an arboretum series that helps visitors identify local animals and plants.

“It will include Anishinaabemowin, as well as English and Latin names,” he said. “On the back, there will be information about the Anishinaabemowin word for insect, which means ‘little spirit.’ The meaning of the word represents quite a culture shift in how we think about insects from the typical Western perspective.”

Most people, he said, don’t care much for insects, but in the Annishinaabe view they have spirits.

Howie said the relationship between the academic world and Indigenous people has not always been as strong as it could be but added: “These are steps on the path to reconciliation.”

For more information on the ways the University is moving towards truth and reconciliation visit Indigenous Initiatives.

Contact:

Justine Richardson

justine.richardson@uoguelph.ca