This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence.

Why do Canadians, especially younger Canadians, have such straight, white teeth? Why are so many parents and so many adults willing to invest in expensive orthodontic treatment?

We recently published an article in the Canadian Bulletin of Medical History that explores the history of orthodontic treatment and the various justifications that have been advanced for undergoing a medical procedure that is often painful, prolonged and expensive.

In the early decades of the 20th century, most adult Canadians were lucky if they had any teeth at all. Among the elderly, dentures were the norm.

In the 1920s, toothpaste manufacturers began to promise that regular use of their product would lead to romantic and financial success. Their advertisements often featured young women with gleaming smiles of straight, white teeth.

After the Second World War, advertisers and governments urged parents to look after their children’s teeth. Water fluoridation proponents stressed that teeth could last a lifetime. Gradually, straight, white smiles — based on natural teeth rather than dentures — became the desired norm.

It was one thing to keep the teeth but it was another to make them straight. Orthodontics emerged as a field in the early part of the 20th century. In Canada, at the start of the Second World War, there were only 40 orthodontists practising in Canada, mostly in Montréal and Toronto. By 1975, there were nearly 500.

Did straight teeth improve self-esteem?

In the 1950s and 1960s, orthodontists tried to convince parents to straighten their children’s teeth by claiming that straight teeth could have a remarkable impact on a child’s self-esteem. American orthodontist John January counselled his fellow orthodontists to tell parents that “the mouth is the psychological key to happiness” and to promise that straight teeth could led to business and romantic success.

Magazine articles argued that bullied children could become popular as their teeth straightened and their “inferiority complexes” disappeared. In wealthy neighbourhoods such as Toronto’s Forest Hill, parents invested in orthodontics to improve their children’s looks, especially their daughters.

As gender scholars have noted, beauty expectations have long been much higher for women than for men and suburban parents believed that investing in their girls’ teeth was part of preparing them for a successful adulthood.

But did straight teeth really contribute to improved self-esteem? The scientific literature on the topic was slim.

A 1966 study suggested that Americans believed that dental appearance was important for finding a job, making friends and even running for office. Most agreed that dental appearance was important for romance.

A few years later, another study claimed that crooked teeth were one of the most difficult “handicaps” a person could have. The author stressed that the degree of psychological distress caused by crooked teeth was not related to the severity of the problem. In their textbooks, orthodontists cited these studies with alacrity.

But the claims were hard to support.

A sociological study of people who had undergone orthodontic treatment found that although they believed that they looked better, the impact on their psychological health was small.

Another study comparing a group who planned to undertake orthodontic treatment with a control group found very few differences between them in terms of self-esteem.

Orthodontics are about looking your best

Orthodontists were also becoming more skeptical about the physical benefits of orthodontic treatment. Studies in the 1980s showed that for most people, orthodontic treatment did not prevent periodontal disease or excessive cavities. In the meantime, the number of studies mounted that suggested orthodontic treatment did not have a significant impact on psychological health.

Surprisingly, this did not lead to decline in orthodontic treatment. Indeed, the number of patients undergoing orthodontic treatment began to increase. There were a variety of reasons for this.

During the 1970s, the number of Canadians covered by private and union dental plans exploded. When these plans included orthodontic treatment, it made it much less expensive.

New devices such as plastic braces, braces worn on the back of the teeth, and new products for affixing braces made treatment times shorter and the braces less noticeable.

Bulky and disfiguring headgear was used less often. The introduction of coloured elastics and wires meant that some children were actually attracted to wearing braces. More adults than ever, especially women, began seeking out orthodontic treatment.

By the 1980s, dentists were far less busy than they had been in previous eras where there was a real shortage of dentists in Canada. To drum up customers, many dentists added orthodontics to their practice and promoted it heavily.

Source

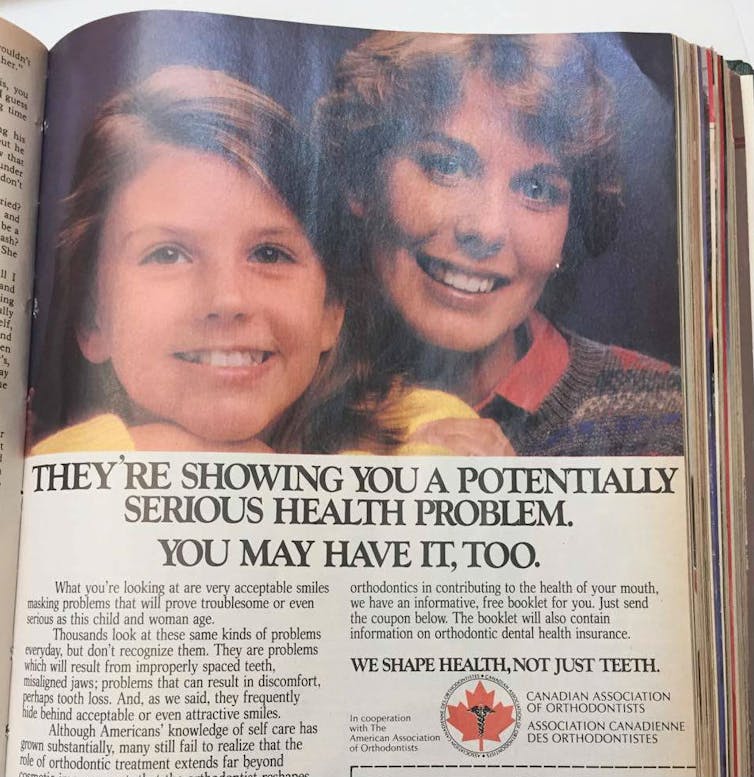

Before-and-after photographs showed prospective patients what they could look like after orthodontic treatment. The Canadian Association of Orthodontists ran advertisements warning that crooked teeth could lead to a “serious health problem.” One parent complained in The Toronto Star in a 1995 article “Reality bites,” that orthodontists threatened parents that their children would never smile if their teeth remained crooked.

The explosion in orthodontics took place alongside a growing demand for cosmetic treatments of all kinds as celebrity culture promoted perfect bodies, perfect faces and perfect smiles.

Today, straight, white teeth have become a social norm and people shell out huge sums for orthodontic treatment for themselves and their children. Orthodontics is no longer sold as a way of overcoming “inferiority complexes.” Instead, it is part of a larger culture of self-improvement that urges all of us to look as good as we can.![]()