Most of us know Anne, from Anne of Green Gables, as a plucky, red-headed orphan with a love for big words and a flair for the dramatic.

The 1908 novel by Canadian novelist Lucy Maud Montgomery was an immediate bestseller. It continues to be taught around the world, and tourists flock to Prince Edward Island to see Montgomery’s childhood home and learn more about Anne.

While Anne of Green Gables is the best known, Montgomery went on to publish eight books about Anne. Anne ultimately marries Gilbert Blythe, the classmate who once called her “carrots” and had a slate broken over his head for his impertinence.

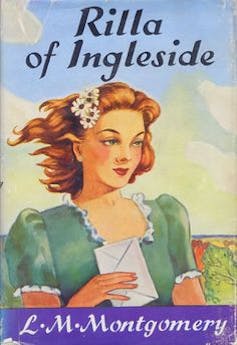

They settle in Glen St. Mary, where Gilbert practises medicine, and they have six children: Jem, Walter, the twins Nan and Di, Shirley and Rilla. In the last of the series, Rilla of Ingleside, the Blythe clan is confronted with the horrors of the First World War.

By this point, Anne is in her 40s and her children are nearly grown. Montgomery is approximately the same age as her heroine, but she got married late in life and her eldest was only a toddler when the war raged. Devastated by the loss of so many young men, Montgomery was grateful that her own sons were too young to fight.

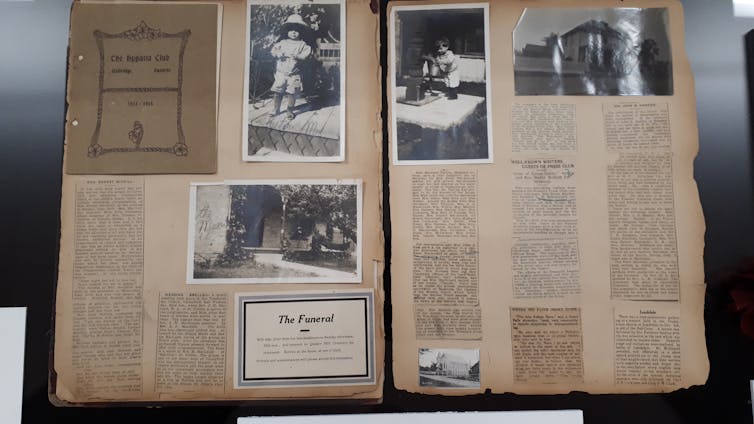

She wrote in her diary: “I thank God Chester is not old enough to go.” In her scrapbooks, she pasted photos of her own young sons alongside newspaper clippings about the war, suggesting both her gratitude and her guilt that other women’s sacrifices were much greater than her own.

And yet, with Rilla of Ingleside, Montgomery would become of one of the architects of our memories of the First World War. As one of the few women to write about the war in Canada, she wrote a novel that glorified the sacrifices made by men and women alike, while acknowledging the pain and horrors of the conflict.

Anne’s children and the war

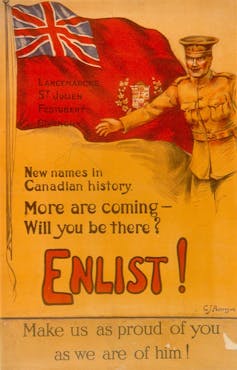

In Rilla, the lives of Anne’s children are transformed by the war. During the First World War, more than 400,000 Canadian men fought overseas and more than 60,000 lost their lives. Most went bravely in search of adventure and out of loyalty to Canada and to the British Empire.

Like Anne’s children, they left behind mothers, wives, sisters and girlfriends, who were usually proud to see them go, but feared for their safety and their comfort in the trenches of Europe. Jem, Anne and Gilbert’s eldest son, enlists the day after war is declared, dreaming of bravery, adventure and honour. Anne is devastated but comes to realize that they must let him go.

Her second son, Walter, was still recovering from typhoid and was not strong enough to enlist right away. Walter is a poet, a sensitive young man, and from the very beginning of the war, he knew war “was a hellish, horrible, hideous thing.”

When he is sent a white feather in the mail to remind him of his cowardice, he wrote to Rilla to say it nearly made him enlist, but then: “I see myself thrusting a bayonet through another man, some woman’s husband” or “I see myself lying alone torn and mangled, burning with thirst on a cold, wet field, surrounded by dead and dying men — and I know I never can.”

But enlist he does. Before he is killed in the Battle of Somme, he pens “The Piper” – a figure he had dreamed of since he was a child. Like John McCrae’s still-famous poem, “In Flanders Fields,” “The Piper” became a fictional global success.

Indeed, as Jonathan Vance has written about in his book Death So Noble: Memory, Meaning and the First World War, the war led to an explosion of poetry, expressing the horrors, the sorrow and the pride that many Canadians felt.

Maternalism, romance and war

The heroine, Rilla, is just 14 when the war breaks out. She’s a silly young girl, excited about going to her first dance. But the war forces her to assume adult responsibilities.

On a journey to collect supplies for the Red Cross, she discovers a child whose mother has just passed away. The father has already enlisted. Unwilling to leave the baby in the care of a drunken caregiver who wanted nothing to do with the child, she takes him home in a soup tureen. Her parents consent to taking him in, but put Rilla in full charge of the infant, now named Jims.

Up until this time, Rilla had little interest in babies, but she throws herself into caring for Jims, studying the best practices for infant feeding and sleeping. Slowly, her maternal instincts blossom. She soon takes a leadership role in her local Junior Red Cross, and she falls in love with Ken, a young man from Toronto, whose family summers in P.E.I.

Ken’s love for Rilla deepens when he comes to wish her goodbye before going to the front. The war baby, Jims, cries terribly and she needs bring him down to the porch, where Ken is touched by tenderness.

The novel concludes with Ken coming to Ingleside for Rilla, who is now grown, “the woman of his dreams.” In contrast to Anne, who had fought against traditional gender roles by seeking an education and a career, Rilla finds her happiness in home and caretaking.

Historians and the First World War

Historians have long claimed that Canada, as a nation, was forged at the battle of Vimy Ridge. As the argument goes, it was not until the First World War, 50 years after Confederation, that Canadians discovered that what bonded them together as a nation was found in the courage of their young solders.

Rilla of Ingleside is part of this mythology. Jem returns home weakened and chastened, but he continues to believe that he has fought to make children safe and for a democratic “new world.” Likewise, Walter’s poem will continue to inspire Canadians and others in the decades to come.

This ignores, of course, the conscription crisis that would deeply divide Canadians later that year. It also glosses over the many losses of the war.

What’s more, as historians Ian McKay and Jamie Swift have argued in The Vimy Trap, Vimyism ignores the many injustices of the war: the concentration camps created for enemy aliens here in Canada, the unjust treatment of pacifists, the shameful treatment of Indigenous soldiers and the fact that Canada was fighting for a British Empire that had many cruelties of its own.

It seems strange to think of our beloved red-headed heroine implicated in the celebration of militarism, but Rilla of Ingleside is a tribute to the sacrifices of war, even while it acknowledges the suffering.

“From Glen Notes to War Notes: A Canadian Perspective on the First World War in Rilla of Ingleside” is currently on view in the Archival and Special Collections’ exhibit gallery on the second floor of the McLaughlin Library at the University of Guelph.

![]() It remains there until October 2018. It features the original Rilla manuscript, as well as Montgomery’s journals, scrapbooks, recipe books, war poetry and other items from the library’s renowned Lucy Maud Montgomery collection.

It remains there until October 2018. It features the original Rilla manuscript, as well as Montgomery’s journals, scrapbooks, recipe books, war poetry and other items from the library’s renowned Lucy Maud Montgomery collection.