Sohrab Rahmaty was four years old when his family arrived in Canada after fleeing Afghanistan during the Soviet invasion begun in 1979. Although he doesn’t remember much of the event, his parents have described how they packed everything up and travelled through Afghanistan’s mountains on horseback.

That earlier 10-year war was largely eclipsed by the conflict that has devastated the country since 2001. But it was the prospect of peace and democracy that took Rahmaty back to Afghanistan last summer to conduct field research for his thesis.

The U of G master’s student in political science returned to Afghanistan – the first Guelph student to conduct research in that country for at least eight years and likely much longer — to learn how a nation establishes democracy after civil war.

Rahmaty is interested in post-conflict democracies, including the role of non-state actors. Earlier he looked at cocoa and its relationship to conflict in the two most recent civil wars in Ivory Coast in western Africa.

For his master’s project, he spent almost two months interviewing politicians, citizens, non-state actors and members of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Germany and Afghanistan.

In what might surprise many western observers, he learned that some so-called warlords might be more of a help than a hindrance in establishing democracy and stability in the country, one of the poorest in the world.

“This study argues that warlords or regional figures have played an important role in Afghanistan’s transition from conflict to nation-building because of the stability which they offer both politically and militarily,” he says.

A presidential election will take place April 5. Incumbent president Hamid Karzai is ineligible to run.

Referring to those “warlords,” Rahmaty says, “I found them to be rational thinkers equal to any western politician. They have to be as politically competent and sophisticated — if not more so – since they are dealing with an environment and political system much more challenging than anything found in western liberal democracies.”

Other key ingredients for establishing democracy after civil conflict include a true end to combat, an agreement on how to share power, and focusing on political parties rather than personalities.

He adds: “Afghanistan has a dynamic political system. People are trying to build the country from the ground up.”

Despite decades of conflict, he says, the country holds other signs of hope, including a youthful population looking for better prospects. “To have had relative peace in many areas of the country is quite an achievement, especially when the majority of the country has known nothing but war. Anyone under 35 has lived through war.”

Calling Afghanistan a “gigantic puzzle,” Prof. Ian Spears, Department of Political Science, says it’s important for democracy to unfold properly in a country where many nations have sunk huge amounts of money and material – not to mention numerous lives. “You really want to make sure it’s the best possible outcome,” he says.

Referring to his student, he says, “What’s interesting about his work is that it’s counterintuitive. He’s exploring why so-called warlords would bury the hatchets. That’s an interesting puzzle, because lots of them probably aren’t prepared to bury hatchets or are wanting to profit in some way.”

Counterintuitive or not, says Spears, “It doesn’t surprise me that they’re interested in a prosperous, coherent, united and, hopefully, in some way democratic Afghanistan. One of his tasks in this paper is to make a persuasive case that these guys are what they say they are.”

The youngest of four siblings, Rahmaty began reading about current events at a young age. “I have always enjoyed reading about international issues to try to better understand what’s going on in the world.”

He completed a BA in political science at Guelph in 2012.

For his grad studies, he thought about looking at civil conflicts in several places but realized he needed to focus on a single case study. That became Afghanistan – not least because of his historical ties.

It was those connections – and his facility with the Afghani language and a number of Canadian friends working for NGOs in Afghanistan – that helped in arranging his trip last summer.

Those factors also meant that Rahmaty met U of G’s Safe International Travel Policy for Students, adopted in 2006. Under special circumstances, U of G may give academic credit to grad students working in extreme or high-risk locations, according to Lynne Mitchell, director and international liaison officer in the Centre for International Programs.

Rahmaty says he was inspired to make the trip partly by his supervisor’s stated convictions about boots-on-the-ground experience. “Political scientists ask questions about states and institutions, but also questions concerning human nature and behaviour. To really understand politics and democracy involving a region, country or people, you have to experience what they experience. You have to be able to identify with the context as they do.”

He felt some uncertainty at first. “You hear about bombings. It’s an insecure place.” But “after two days, I felt relaxed. I came back to myself.”

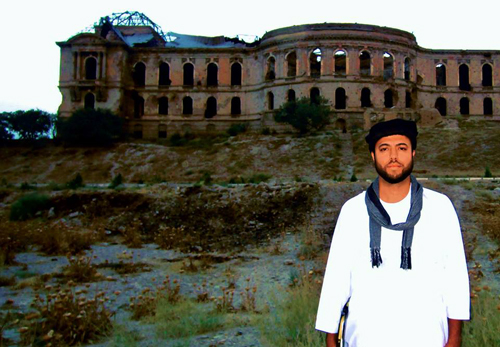

Last August and September, he travelled between Kabul and Mazari Sharif, the latter near the country’s northern border with Uzbekistan.

“I found the people politically, socially and culturally attuned,” he says. “They may not have had the opportunity to gain formal education, but they are a remarkably bright and dynamic people, as all people must be to be able to endure conflict yet remain hopeful.”

Now writing his thesis, he hopes to work for a peace and conflict studies institute.