High intensity workouts are a great way to get in exercise quickly, even if they can leave your muscles exhausted. But can those workouts also tire out or damage the heart?

A growing number of studies in recent years has suggested that some forms of intense or prolonged exercise can temporarily fatigue the heart – an organ long known to never need a rest.

The phenomenon, dubbed “exercise-induced cardiac fatigue,” was thought to affect only the most extreme athletes in ultramarathons or other strenuous sports. But recent research suggests cardiac fatigue can occur even during shorter bouts of strenuous exercise.

Now, new University of Guelph research published in the Journal of Applied Physiology questions whether the heart “fatigue” others have observed is really fatigue at all or just a normal part of the heart adjusting to the demands of exercise.

“Exercise is well known to benefit health and longevity, but we needed to consider if there can be too much of a good thing that might cause the heart to fatigue or change function, even transiently,” said Dr. Jamie Burr, an exercise physiologist in the College of Biological Science.

Burr and PhD student Dr. Alexandra Coates, conducted experiments to see how much intensity would be needed to create signs of cardiac fatigue. To their surprise, they found that those performing even the most strenuous exercise saw no worse changes to their hearts than those who performed moderate exercise.

“It’s good news for those who engage in intense exercise, as it shows us that the heart is pretty resilient, but it also leaves researchers like me with questions,” said Coates, the study’s lead author and now a postdoctoral fellow.

Cardiac changes were the same after every workout

“In our earlier research, we found that long duration didn’t lead to cardiac fatigue, and that even athletes running 160 kilometres showed no significant differences in cardiac alterations compared to those running 25 kilometres. So, we thought, ‘Well, maybe it’s intensity and not the duration that brings this on.’”

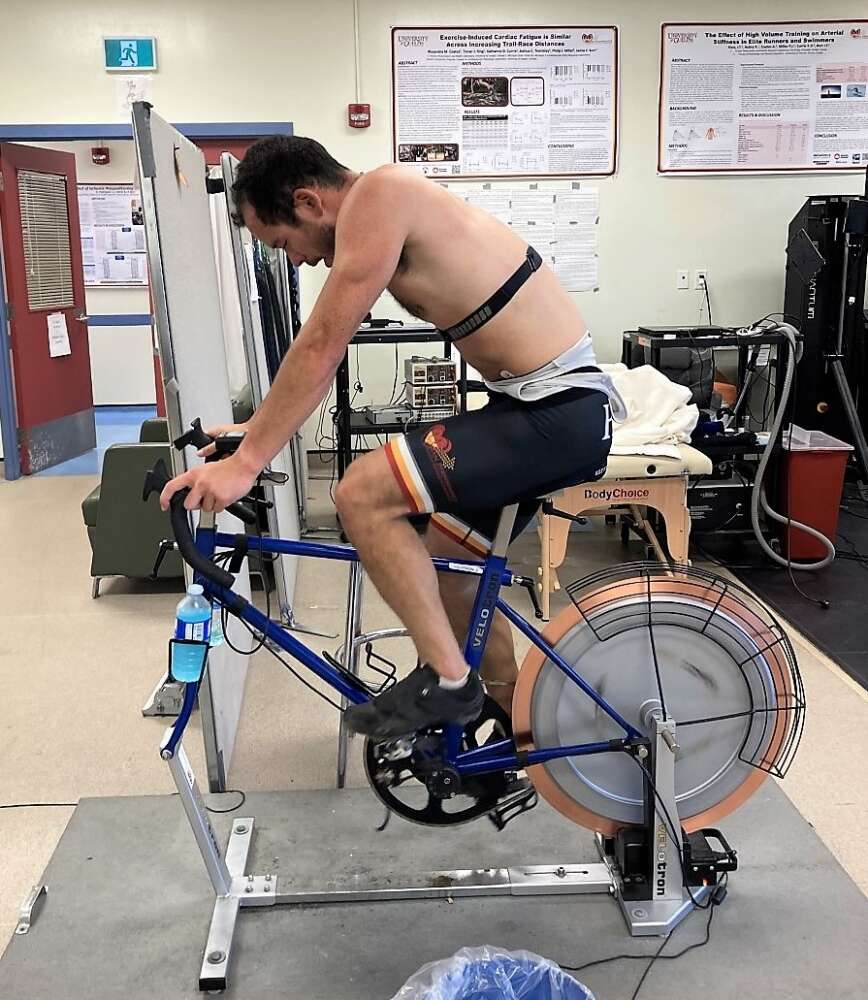

To find out, Coates, Burr and Department of Human Health and Nutritional Sciences (HHNS) colleague Dr. Phil Millar recruited 17 men and women athletes for four gruelling cycling tests, In the first, they performed several intense intervals called a Wingate test over a 30-minute bike ride; another of Wingate tests over a 90-minute ride; a 90-minute ride at a moderate pace and a 3-hour ride at a moderate pace.

Stress echocardiography during the experiments helped measure various changes in the left and right cardiac ventricles.

“This was the first study to compare vastly different exercise conditions in the same individuals,” said Coates. “We expected to see greater cardiac fatigue after the tough intervals but while we noted temporary changes in cardiac function afterwards, the changes were the same after every kind of workout. So that raises the question: are we even seeing cardiac fatigue at all?”

Cardiac changes previously reported may represent normal function

Coates said it’s possible researchers are missing what’s happening to the heart because exercise itself induces hemodynamic (blood volume and pressure-related) loading conditions that alter how hard the heart has to work to pump blood to the body. The altered cardiac function seen after the cycling tests was likely due to these altered loading conditions rather than cardiac fatigue, the researchers say.

“This recent line of work suggests that at least some of the changes previously reported to be concerning may represent normal function, rather than something we really need to worry about,” said Burr.

The team also found that the male athletes experienced greater cardiac changes in some measures than the women, and their heart rates remained elevated for longer after exercise. This may suggest men experience greater cardiovascular stress during and following exercise, but they cautioned that their sample size was small and it’s possible the women had greater relative fitness to begin with.

The researchers note their studies were conducted on athletes under the age of 40 who had high levels of fitness, so their findings may not be applicable to everyone, particularly those with heart disease.

They also note it is possible some forms of cardiac fatigue do occur under certain circumstances, particularly concerning the right side of the heart, which is less robust than the left, but it remains unclear who may be affected and after what durations or intensities of exercise.

The research was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, and the Ontario Ministry of Research, Innovation, and Science.

Contact:

Dr. Jamie Burr

burrj@uoguelph.ca