The underlying causes of the semiconductor chip shortage that began with the pandemic lockdowns are not going away anytime soon, warns a University of Guelph computer engineer.

Dr. Stefano Gregori is a professor in the College of Engineering and Physical Sciences and the founder and director of the Microelectronics Research Laboratory. In the School of Engineering, he combines theory and experiment and uses real-world applications to study integrated microsystems like microsensors and circuits for the Internet of Things and wearables.

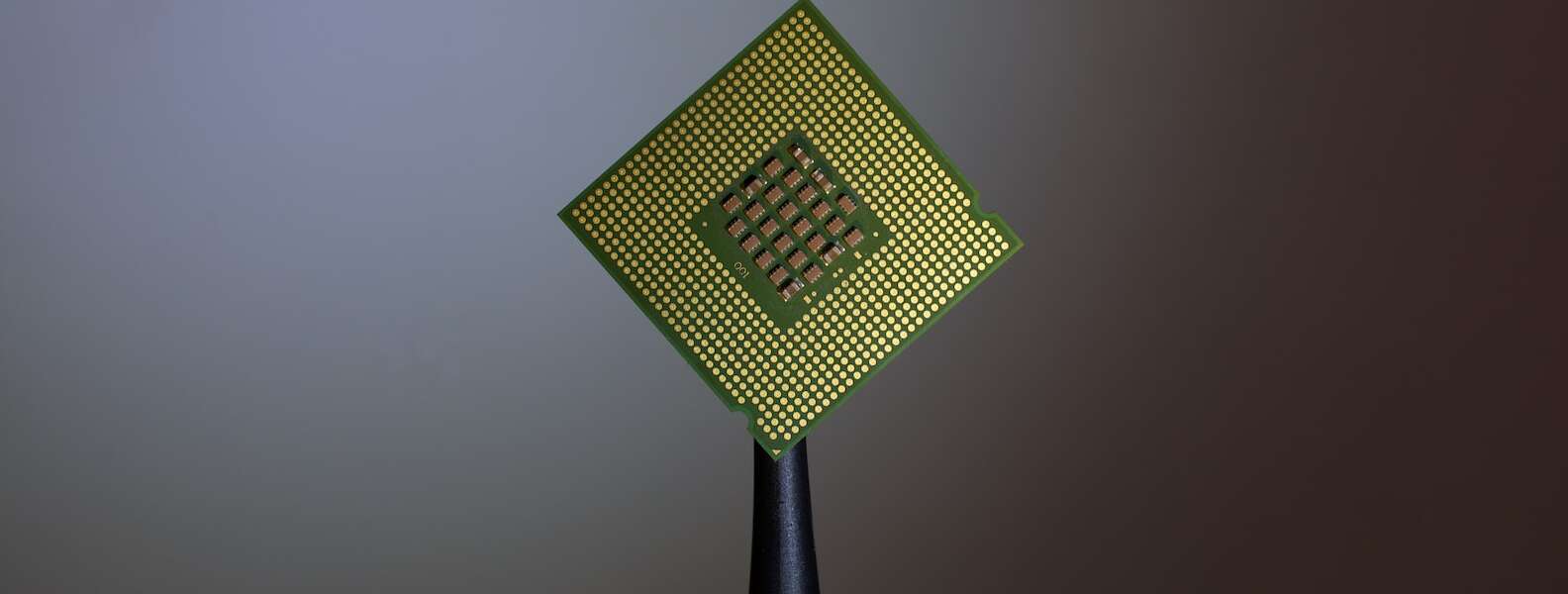

The current semiconductor chip shortage started because of a rapidly changing demand for a product that typically takes six months and millions of dollars in capital investment to make and is used in everything from electronics to cars to medical equipment, says Gregori.

“Although the shortage crisis was amplified by the pandemic, the underlying causes are going to last until chip production is increased and critical vulnerabilities are addressed,” he adds. “The extremely fragile and complex supply chain and the shortages are problems that highlight how much the world is connected.”

One way to mitigate the shortage, which recently eased for some companies, is to invest in a resilient supply chain with improved domestic capability, says Gregori.

Canada should step up with semiconductor investments

Several countries and regions, including Taiwan, China, Singapore, South Korea, the European Union and the United States, have already invested billions into their semiconductor industries, although Canada has committed only $150 million this year, notes Gregori.

“Maintaining technological independence from global supply chains is a defining interest for Canada, and it will be that way in the decades to come,” he says, adding he’d like to see further government support directed to the industry.

Because semiconductor chips are used in almost everything, they will underpin new technologies such as agricultural technology, clean energy, e-health and AI, Gregori explains. For example, electric cars will be more difficult to produce in Canada than conventional gas-powered cars because electric vehicles have more than twice as many chips.

“Not only is establishing a domestic semiconductor industry critical to Canada’s national security, economy and technological interests, it will also yield significant long-term economic benefits and highly skilled employment opportunities,” says Gregori.

He is available for interviews.

Contact:

Stefano Gregori

sgregori@uoguelph.ca