This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

By S. Ashleigh Weeden, PhD candidate, School of Environmental Design & Rural Development

One year into the COVID-19 pandemic, communities across Canada have cycled through two waves of infections and control measures. As more virulent new variants enter the arena in our battle against the virus, many are preparing for a third wave that stands to be the most serious and significant yet.

On Feb. 17 — just one day after Ontario’s formal stay-at-home order lifted — Dr. Eileen de Villa, Toronto’s medical officer, stated that she had never been more worried about the threat of COVID-19.

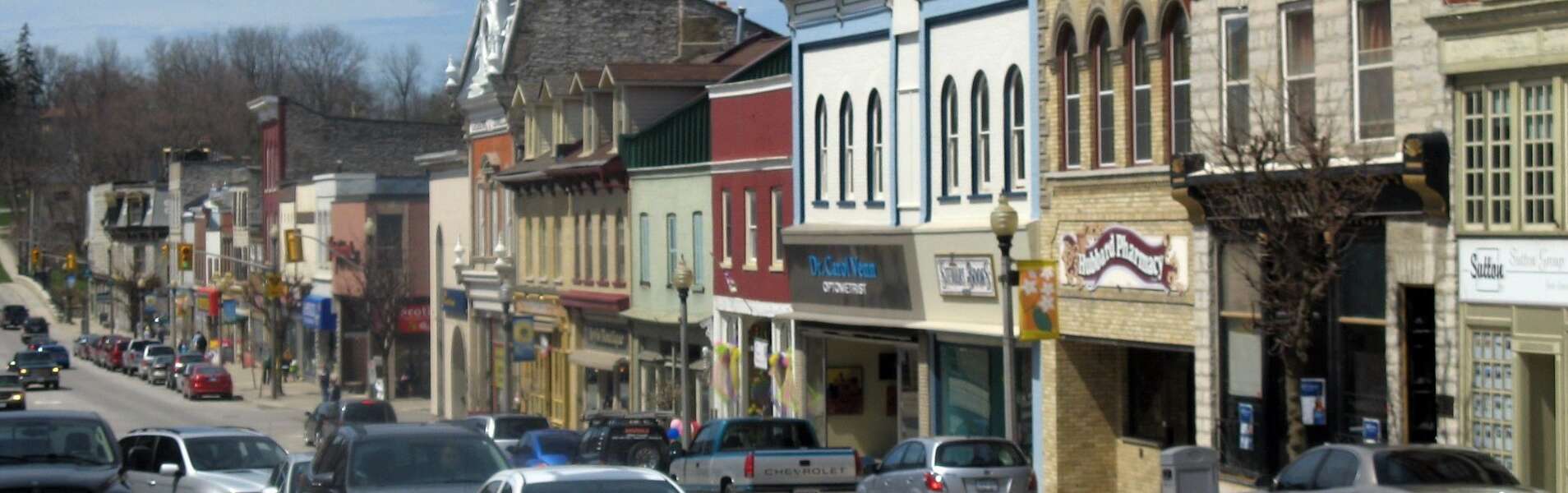

De Villa’s concerns are echoed by many outside the Greater Toronto Area and across Canada. Outbreaks have started to emerge outside the previous hotpots, with places like Barrie and North Bay in Ontario seeing large spikes in the coronavirus variants that originated in the United Kingdom (B117) and South Africa (N501Y).

Regional reopenings without any strict barriers to intra-provincial travel have lead to the strange contrast between areas still in lockdown and crowded scenes like the one at a HomeSense in Vaughn, Ont. Ski hills, restaurants and other businesses have reopened in some areas, however leaders in those communities continue to ask people not to travel to them.

Some of the worst outbreaks in Canada have happened in rural communities, such as the April 2020 outbreak at the Cargill meat-packing plant in Alberta; the province’s highest rates of the virus continue to be associated with rural areas. Nunavut, which had previously managed to keep COVID-19 out, experienced some of the fastest rising case numbers in late 2020.

Small communities, outsized impacts

Almost a year ago, I wrote about the tensions involved in conversations about “the right to be rural” and the implications of “region hopping” during the pandemic. While these tensions appeared to ease somewhat when case numbers declined in late summer, they’ve started to escalate again as we navigate the second (and potentially third) wave.

The fears expressed early in the pandemic about overwhelmed health-care systems and strained local supply chains. Challenges to service delivery continue to simmer. Many rural, remote and small communities were able to weather these challenges fairly well early in the pandemic — to the extent that patients from overwhelmed hospitals in urban hotspots were being redirected to smaller centres.

In other communities, patients in need of critical care faced the prospect of being triaged in their cars in Manitoba and nurses worked 16-hour days in rural Québec communities like Saguenay Lac-Saint-Jean, which produces one-third of Canada’s aluminum.

On Feb. 17, the Grey-Bruce Health Unit recorded its first case of a COVID-19 variant. Critically, the case is associated with someone whose primary residence is outside the region and who was isolating at their secondary residence. While inter-regional travel in the province is no longer strictly limited to only essential reasons, it remains heavily discouraged due to concerns about spread in exactly this manner.

However, even when the stay-at-home order was in place, there was confusion about what was considered essential and how the restrictions would be enforced.

Beyond trying to manage the impatience of people who are looking to escape or work around pandemic protections, many regions must also contend with inter-provincial travel of essential workers and those who bring critical goods like food, medicine and other necessities.

Restricting travel

Restrictions on travel across provincial borders have been easier to manage, but they have not been perfect solutions. The Atlantic Bubble was largely regarded as a successful case study in controlling the spread of the virus — until it wasn’t.

No one expected an outbreak in Newfoundland and Labrador, where the explosion of cases connected to the variant identified in the U.K. disrupted a provincial election, led to calls for inter-regional restrictions to protect vulnerable communities and emphasized just vulnerable we are, no matter where we live.

In light of these trends and challenges, some leaders, like the mayor of Sudbury, Ont., called for checkpoints and controls on inter-regional travel, much like the measures instituted in other jurisdictions such as Australia.

As continued public health measures produce pandemic fatigue and front-line worker burn-out, restrictions on our daily lives chafe against our right to freedom of movement. While policy-makers wrestle with the political hornet’s nest of restricting travel between regions, individual businesses are taking matters into their own hands and limiting service to locals only.

We can’t police our way out of the pandemic

As the world’s second largest country, developing effective movement controls that can be equally and equitably enforced across Canada’s 9.9 million square kilometres (approximately 40 times the size of the United Kingdom) is nearly impossible on both the individual and policy levels. In most provinces, public health units cover multiple municipalities in arrangements that don’t always reflect other local governance arrangements.

In Ontario, 34 health units are responsible for 444 municipalities. Where would we install barriers for inter-regional travel? Who would monitor those barriers? And is it an effective use of finite resources to monitor every access point, whether by gravel road, lake access or highway?

To curb region-hopping at the local level would require an extraordinary level of co-ordination among all policy players, as well as enforcement capacity based on clear, consistent directives that adapt to regional contexts. This is something we have not exactly succeeded at to date.

Practicalities aside, experts have cautioned that we can’t “police our way out of the pandemic.” And many marginalized people are rightfully concerned that such approaches put them at greater risk.

Fail to plan, plan to fail

In Ontario, the responsibility for the vaccine rollout been passed on to local public health units, potentially producing 34 different vaccination strategies. In both Alberta and Ontario, a digital-first strategy of online booking portals ignores the reality of many rural, remote and marginalized communities.

A chronic lack of both transparency and accuracy in data collection and pandemic planning across all orders of governments has produced what epidemiologist Raywat Deonandan calls a “failure of imagination.” This lack of responsive planning could leave those most vulnerable to the virus in rural and remote regions waiting longer than their urban counterparts for vaccines.

The pandemic has not created these jurisdictional challenges, it’s just revealed how easily important and urgent work can fall through the bureaucratic cracks. The lessons we are learning during this pandemic continue to remind us that our individual actions have community impacts. Our way forward will have to depend on a mix of policies and practices that remind us that we live in a society where our personal well-being is inextricable from the well-being of those around us.