This article originally appeared in The Conversation and was republished by the National Post.

By Sabrina Rondeau , PhD researcher in the School of Environmental Sciences.

Finding new and environmentally friendly ways to control pests is both challenging and exciting. This is even more true when it involves developing a tool to address one of the greatest threats to honeybee colonies.

Honeybees are extremely important insects because they pollinate much of the food we eat and other crops we rely upon. But the essential services they provide are in danger since massive honeybee losses are continually reported in many countries.

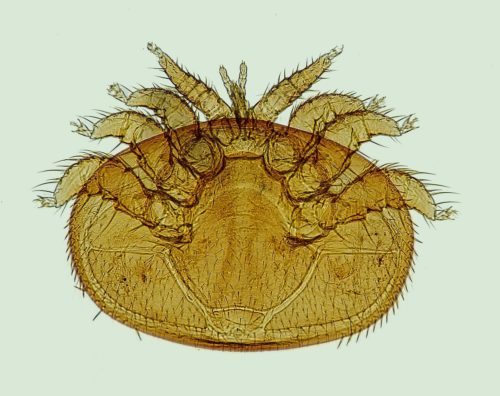

The main cause of these colony losses is the Varroa mite. Also called Varroa destructor, Varroa mites are tiny red-brown external parasites that feed and live on honeybees. Like tiny vampires, they weaken the bees by sucking up their hemolymph — the blood of insects — and their fat bodies. The parasitic mites also transmit bee diseases that can ultimately wipe out entire bee colonies.

As part of my master’s degree research led by Drs. Valérie Fournier and Pierre Giovenazzo at the Université Laval, we showed that a promising biological candidate to control the deadly parasite is unfortunately ineffective. Our new research underlines why it’s so difficult to sustainably control the pest.

Beekeepers’ greatest challenge

Native to Asia, the Varroa mite was introduced to North America about 30 years ago. Since then, it has caused major bee deaths and economic losses for beekeepers.

The Western honeybee has no defence against Varroa mites, which is why infestations with Varroa require human intervention. If left untreated, an infested colony is doomed to certain death.

Currently, the use of chemicals is the only option to effectively control Varroa infestations. These chemicals, known as acaricides, are applied directly into the beehives — most often in the form of chemical-impregnated strips — and aim to kill the pest.

Although these products may be helpful in controlling the infestation, they are also variably toxic to bees and can contaminate wax and honey. The rapid development of mite resistance toward chemicals is another issue that now limits the use of what were once the most effective compounds.

Ultimately, beekeepers often feel forced to use chemicals at the expense of the health of their bees.

Attacking the invaders

As an alternative to chemicals, fighting Varroa mites with natural enemies would represent a safer avenue for colony health and the environment. This approach is known as biocontrol and can be done by using predators, fungi and other pathogens that target Varroa mites and reduce their population.

So far, very little research has been done on the use of biocontrol organisms to fight Varroa mites. In fact, it is very difficult to find a living organism that would control Varroa infestations without killing the bees themselves.

Besides killing Varroa mites, a good biocontrol agent must also be able to survive and thrive in the hot and humid conditions of the beehive and must be safe for honeybee eggs and young and adult bees.

Bringing in the troops

In recent years, a predatory mite has been flagged as being particularly promising to control the Varroa, bringing hope to beekeepers. This beneficial mite, called Stratiolaelaps scimitus, has been shown to attack and feed upon the Varroa in the laboratory.

Stratiolaelaps scimitus occurs naturally in North American soils. The mite is a predator, feeding on various soil organisms including worms, insect larvae and other small invertebrates. The mite is already commercially available because it is useful in controlling several pests in agriculture.

The use of this new potential ally has been promoted by some biocontrol suppliers in North America and Europe. But to date, its effectiveness in the hive has never been confirmed.

To prevent potential harmful effects from the use of this predatory mite in bee colonies, assessing both the risks associated with its use for bees and its effectiveness in the hive was essential. That’s what our research team at the Université Laval did.

The first part of our study showed that the predator does not feed on the bees’ offspring within the hive, which makes it fairly safe for use in honeybee colonies.

Unfortunately, the research also showed that the predatory mite is unable to control Varroa populations when introduced in bee colonies during the fall season — the most critical period for Varroa treatments.

Risk/benefit analysis

Many reasons explain this unfortunate lack of effectiveness. For instance, even if the predator kills Varroa mites in the laboratory, it does so only when the parasites are not attached to the adult bees and when there is no other food available. Obviously, the conditions of a honeybee colony are much more complex than that.

Free Varroa mites are almost nonexistent in the hive. Rather, most of the Varroa are either parasitizing young developing bees in capped cells or strongly attached to the body of the adult bees.

This makes Varroa mites hard to access for any potential biocontrol agent, which must attack those Varroa attached to adult bees to be useful. Stratiolaelaps scimitus is unable to do that.

The predatory mite also has a generalist diet, meaning that it can feed on a wide range of prey. This is a problem since a variety of other “food” is available within the beehive, including pollen-feeding mites and small insects. These other prey are smaller and softer than Varroa mites, which makes them easier to prey on.

Essentially, the ecology and behaviour of both the pest and the predator, as well as some characteristics of the hive environment itself, prevent Varroa mites from being attacked and killed.

Bee aware

Varroa mite biocontrol is obviously appealing for various reasons but has its share of challenges — especially when it involves both host-parasite and prey-predator interactions. Based on the most recent knowledge on the subject, the use of predatory mites to replace other Varroa treatments of known effectiveness is strongly discouraged.

Despite the many challenges it entails, more research on alternative methods of Varroa mite control is badly needed. In the meantime, beekeepers can continue to use soft varroacides that contain naturally-occuring chemicals, as opposed to hard varroacides containing synthetic chemicals, as an acceptable option for Varroa mite control.

And as for Stratiolaelaps scimitus, it sounds like it will remain a kind of fantasy about what could have been a very neat tool to tackle the bee killer parasite.![]()