By , School of English and Theatre Studies, University of Guelph

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence.

Now that the U.S. government is threatening to define gender as only male or female, we need to fight more than ever for transgender rights. But the idea there should be no gender categories and we should live in a label-free world, as some have argued, is a utopian dream.

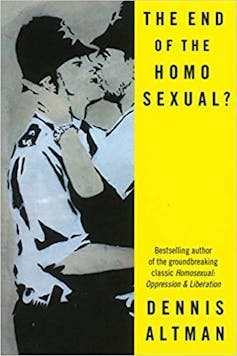

Pioneering scholar Dennis Altman spoke for many gay and lesbian activists at the beginning of the modern queer rights movement in 1971 when he suggested the battle for acceptance of human and legal rights for gay and lesbian people had only one goal: the eradication of the need for any such rights at all.

According to Altman, categories of sexuality were a necessary evil, but in an ideal world they would be replaced by “a new human who is no longer imprisoned by limitations of sexuality and compassion….”

Cultural theorists Daniel Harris and Bert Archer continue to embrace Altman’s original utopian vision. Harris gleefully announced the death of both gay culture and straight oppression in his 1997 book, The Rise and Fall of Gay Culture:

“Is the demise of gay culture such a great tragedy after all? Certainly, it is an inevitable tragedy and only a nostalgic fool would want to prevent it from happening in the light of the fact that the flourishing of gay culture depends on the persistence of the oppression we have struggled so hard to eliminate.”

By 2002 Bert Archer intoned that “sexual identity … is in the end, a house built on sand, the living in which makes us … more anxious, less happy people than we might be otherwise.” And Altman’s 2013 book The End of the Homosexual? reaffirmed his earlier idealism: “Why should we assume that the current emphasis on ‘LGBTI’ identities will remain as the defining ways of thinking?”

It’s hard to disagree with a vision of the future in which everyone feels completely free to love as they wish. The problem is that we have seen no sign of this happening in reality.

A transgender utopia?

While there have been many solid civil rights gains for queer people, there are no signs of an emerging queer utopia yet. For example, a baker in Colorado took his objection to baking a gay wedding cake to the United States Supreme Court and won.

For those who still harbour fantasies of a world without categories, the transgender movement may be one answer.

Many transgender theorists offer imaginings of a utopia in which the gender binary disappears. For example, Stephen Wittle describes a transgender utopia where one can “become queer by refusing gender ascription”; activist Riki Ann Wilchins compares gender binary to a fascist dictatorship: “the purpose of a gender regime is to regulate these meanings and to punish those who transgress them”; and Kate Bornstein — perhaps the most ardent supporter of a “no gender” future — sees it within reach: “In this struggle for our freedom of expression there comes a point where the gender system reveals itself to be not only oppressive but silly.”

What about sex?

Some scholars object to the idea of a “non-gendered utopia.” For example, philosopher Jean Baudrillard thinks that gender is sexy and he fears we will become less sexual without it. Literary critic Rita Felski characterizes Baudrillard’s objections as the whining of a frustrated male chauvinist: “In Baudrillard’s relentless heterosexual and sexist universe, this loss of desire is attributed to the disappearance of sexual difference.”

But it is not only sexually frustrated, heterosexist, biological males who are deeply attached to gender. Patrick Califia was a well-known lesbian theorist (Pat Califia) before transitioning in 1997. He now sees himself as a transgender person.

Califia has romanticized the gender binary in a way that some might see as more sexist than Baudrillard: “when I crave a seamless male image, what I’m mostly longing for is a consistency and invisibility, the social convenience of passing without being questioned or challenged.” Though Califia acknowledges that men must learn how to “express their maleness in an honourable and respectful way,” he also describes what it feels like under the influence of male hormones: “I can absolutely understand why men can (and must!) pay $40 for a blowjob on the way home from work, or get caught jacking off in public toilets.”

Though gay and lesbian people often disagree about the nature or importance of “gay culture,” they have historically categorized themselves according to their sexual attractions. In contrast, the transgender movement often explicitly define their philosophy as being about feelings, not the body.

The Accord Alliance, which provides information on differences of sex development, tells us that “‘Sex’ is the term we use to refer to a person’s sexual anatomy…. ‘Gender’ is the term we use to refer to how a person feels about himself.”

Abandoning utopias

Although it may seem far-fetched, we can compare the transgender movement to another very significant, sexless, North American utopian movement. Ann Lee founded the Shakers in 1776. Shakers were “radical” for their time in many ways; 75 years before emancipation and 150 years before suffrage, Shakers were already practising social, sexual, economic and spiritual equality. Being a part of Shaker culture meant “non-Christians and all races were welcome.”

It’s easy to make fun of Shakers, who are so-called because they abjured sex. They were famous for their emotionally charged church services in which they danced wildly without making physical contact with others. Whatever you think of the Shaker commitment to celibacy, it may have contributed to their remarkable productiveness; they were responsible for many cherished modern inventions — among them, the clothespin and the circular saw. Like transgender theorists, their utopia was not a sexual one. But it offered acceptance of all — however they self-identified.

Shakers were ahead of their time in advancing the noble ideal of “social, economic and spiritual equality.” The problem is that they were utopians — hoping and imagining that everyone would share their craving for universal celibacy.

Perhaps we can learn a lesson from the Shakers: it might finally be time to abandon utopias? From the start, gays and lesbians harboured utopian visions, but there is no sign these visions will come to fruition any day soon.

Universal acceptance

Many may wish for universal acceptance of all genders; some want to give up gender altogether. But for many of us, gender can be sexy. One thing that is not likely to change is the fact that people are different, and those differences can be what attracts us to each other. So most people — for better or worse — cling to their identities, needs and desires.

U.S. President Donald Trump and his administration have recently considered launching an attack on people who self-identify outside the gender binary by imposing a new definition of gender that would define sex as either male or female; any dispute about one’s sex would have to be clarified through genetic testing. A move like this would deny federal recognition and civil rights protections to transgender Americans.

People should be able to self-identify as gay or straight, and as male, female or genderqueer, non-binary, trans, intersexed — or any category they desire. We need to oppose Trump’s ideas and fight for these rights.

But it makes no sense to argue for a utopia without gender categories. Is there a way to destabilize gender identity categories without wiping out gender forever?

It’s important to remember, though, that abandoning utopias does not mean abandoning our ideals — or our hopes of achieving them. Utopias are romantic and seductive, but it might make more sense to try and gently alter our day-to-day reality, one day at a time.![]()