The tuberculosis (TB) vaccine hasn’t changed much since it was first used on humans almost a century ago, yet the disease is still prevalent in Canada’s aboriginal communities and in developing countries.

In Canada, the TB vaccine is only recommended for those who live or work in high-risk areas for TB transmission. The vaccine is only 51 per cent effective against preventing any type of TB infection, according to the Government of Canada’s Immunization Guide.

“It’s not effective anymore, especially in adults,” says University of Guelph chemistry professor Mario Monteiro. “It’s not even used now in North America.”

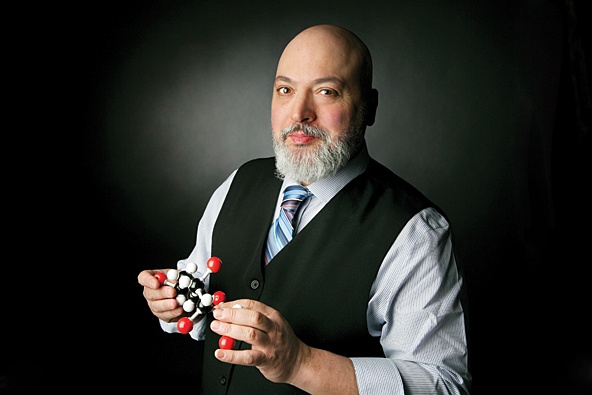

Monteiro is working on a new — and hopefully more effective — type of TB vaccine that uses a plant-based ingredient to trigger an immune response in the body.

Monteiro’s lab is best known for developing vaccines against gastrointestinal bugs such as Clostridium difficile and Campylobacter jejuni, both of which cause diarrhea. The Clostridium difficile vaccine was named “Innovation of the Year” for 2016 by U of G’s Catalyst Centre, which licenced the vaccine to a private company. The Campylobacter jejuni vaccine was funded by the U.S. Navy and is currently in phase one of human trials.

Both vaccines use polysaccharides (long sugar molecules found on bacterial cell surfaces) to fire up the body’s immune system. Monteiro decided to use a similar approach with TB.

“With those two vaccines under our belt, we thought, why not tackle probably the biggest challenge there is, which is TB,” he says. “TB is still the biggest scourge around the world.”

The infectious lung disease is particularly dangerous for young children and people living with HIV/AIDS. Cases of multi-drug resistant TB are on the rise, making the need for a new vaccine even more pressing.

In collaboration with Prof. Praveen Saxena, Department of Plant Agriculture, Monteiro’s lab also studies medicinal plants such as St. John’s Wort and their effects on the immune system. Monteiro noticed the plant produces a polysaccharide region similar to an area in the cell wall of the TB mycobacterium.

Plants with these types of polysaccharide structures have properties that stimulate the immune system, as do the polysaccharides found in the cell wall of the TB mycobacterium, he explains. “There has to be something inherent about these polysaccharide structures that provoke the rise of immune system markers in the host.”

Instead of growing TB mycobacteria for the vaccine, which must be done safely in a biohazard lab, Monteiro is isolating and characterizing parts of the St. John’s Wort polysaccharide. This process yields 1,000-fold more polysaccharide material from St. John’s Wort than from TB mycobacteria.

The polysaccharides from the TB mycobacteria are being used as targets for the vaccine. When the body is exposed to TB mycobacteria, the immune system will be equipped with the specific antibodies to recognize the cell surface of the microorganism and respond immediately, says Monteiro.

Pharmaceutical companies developing TB vaccines today are using proteins or viral vectors (viruses that carry DNA from pathogenic bacteria). The polysaccharide-based TB vaccine complements these approaches, says Monteiro, adding that the polysaccharides from St. John’s Wort can be combined with TB proteins to make a dual-antigen conjugate vaccine.

He says the vaccine is in the early stages of development.

“It’s clever that we’re using a plant polysaccharide to fight a microorganism,” he says. “I’ve never seen this before. You can actually say vaccines can grow on trees.”