Each year Canada honours the legacy of black Canadians during Black History Month in February, and Canadians can gain insight into the experiences of black Canadians and their vital role in the country’s history. But what many people might not know is these contributions extended beyond the border.

In the years before the American Civil War, many African-Americans moved to Canada – or, more accurately, the territories that would become Canada in 1867 – seeking a better life without slavery or restrictive laws. Racism was still a reality in Canada, but it was not institutionalized as it was in the U.S.

Yet after the war began in 1861 and Abraham Lincoln changed the law to allow black men to serve in the army, nearly 2,500 African-Canadians and African Americans volunteered to leave Canada and fight in the Union army and navy. In some parts of Canada, these volunteers accounted for as much as 14 per cent of the black population.

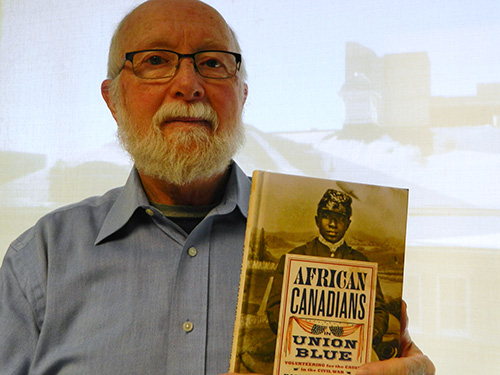

This is a part of Canadian black history that many of us don’t know, says Richard Reid, U of G history professor emeritus. His book, African Canadians in Union Blue, shares these stories. “We know very little of most of these men,” he says. “I can just open small windows into complex lives through my research and writing.”

War is always dangerous, but it was even worse for these black soldiers, who, if captured, could be killed or enslaved, and the white officers leading them faced punishment for “inciting servile insurrection.” In fact, there were a number of battles that resulted in the alleged massacre of black soldiers, as described in Reid’s book.

Why were these Canadians prepared to take such a risk? “I can only speculate, but I think my speculation is good,” says Reid. “It was an altruistic war, and I think the call to fight against slavery touched not only the black volunteers, but also the much larger numbers of white Canadian volunteers.”

Money was also a factor. As the war dragged on and fewer people volunteered for service, the government began offering significant sums to encourage people to sign up. Initially, black soldiers were paid about half the amount received by their white colleagues, but only when that differential was resolved, did most African- Canadians volunteer.

In one chapter Reid focuses on the lives of black doctors working in the Union army. “It was hard to decide whether I should emphasize the advances that had made it possible for these men to become doctors, or the racism and intolerance that inhibited their careers.”

Consider Alexander Augusta, who was refused entrance by U.S. medical schools, so he enrolled at the University of Toronto. After graduation in 1856, he stayed in Toronto to practice, and did not head back to the U.S. until Lincoln authorized the use of black troops.

Reid says that when Augusta arrived to write the required medical exam for entrance into the army, the reaction was, “There must be some mistake; this man is black.” Augusta did so well on the exam that he was given the rank of major and was made the senior surgeon, assigned to care for both black enlisted men and the white officers, in one regiment. He endured protests and insults from others in the army, including the white physicians, yet in 1864 he was invited to a soiree given by Lincoln. After the war, he became the first African-American to teach at a U.S. medical school.

Until recently, most historians had assumed the number of black Canadians in the American Civil War was small. Reid’s painstaking review of the documents has revealed a different story: “This was a fight that very much mattered to the African-Canadians of the time.”