What would you pay to spend a couple of weeks trawling through European museum collections of flies dating back to the Victorian era? For this past summer’s round of German and Danish institutions, it cost Morgan Jackson — zero.

The Guelph grad student received full funding for his research trip from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. — with one stipulation. Jackson needed to post regular tweets and blog articles and generally provide social media commentary that would take viewers and readers along as virtual companions on his trip abroad.

That support of new tools by an institution with its own roots in Victorian times demonstrates the growing influence of social media as a way of communicating science to the masses, says Jackson. And that resonates with a PhD candidate who is almost as passionate about sharing “cool science” with the world as he is about studying stilt-legged flies for his thesis.

It’s about more than blogging and tweeting. Now working in the U of G Insect Collection with Prof. Steve Marshall, School of Environmental Sciences, Jackson has become a kind of one-man science outreach effort.

He’s co-host and co-producer of a weekly science podcast called Breaking Bio. Co-producers are all researchers or grad students at various universities. Besides Jackson, the current lineup includes researchers in the United States and the United Kingdom.

In this virtual round table, the group members log in together to interview selected guests about biology, science and the academic life. “It’s like four or five scientists around a table at the pub,” he says. Or, he adds, “It’s like CBC’s Quirks and Quarks but with more quirks and fewer quarks.”

Each 30-minute podcast airs live and is stored online for future viewing (http://breakingbio.com/). Since last year, the group has made almost 70 episodes.

In late September, they talked to University of Hawaii biologist Hope Jahren about plants and climate change. Other recent guests have included David Gorski, an American surgical oncologist and alternative medicine critic; Janna Eaves, co-founder of Miss Possible, a startup company intended to promote science among girls; and Natalie Bray, a Columbia University grad student looking at soil microbes and ecology.

Guelph computer scientist Prof. Dan Gillis has appeared on the podcast to discuss the Farm To Fork website connecting food donors with food banks and pantries.

Each episode attracts 200 to 300 listeners, says Jackson. Overall, he adds, they have about 1,500 followers.

Besides producing the podcast, Jackson maintains a blog called www.biodiversityinfocus.com/blog. There he posted updates of his European travels this past summer. He also wrote recently about the centenary of the passenger pigeon’s extinction – and the reappearance of a mite species thought to have vanished with its lost bird host.

He also posts photos from the field and museum at http://instagram.com/morgandjackson.

If he’s keen to use social media to share science, he’s also interested in promoting new tools so that anyone armed with a smartphone or camera can “do” science as well. “Everyone with a cellphone in their pocket can contribute to natural history research by snapping photos.”

Millions of nature photos and videos end up on sites ranging from Flickr and Instagram to YouTube. That trove might hold previously undiscovered species or previously unseen animal behaviours just waiting for a sharp-eyed naturalist to spot them.

Take the entomologist who saw a photo of an insect called a lacewing while visiting Flickr. The bug turned out to be a new lacewing species; the scientist and the photographer teamed up to write a paper describing the insect.

That anecdote was part of a recent Atlantic magazine story that quoted Jackson discussing the growth of citizen science. He says he’s seen blog postings about the first-ever record of a species in a particular geographic location and tweets that are the first published records of new species of creatures.

“There’s potential to take advantage of thousands of people with data recorders in their pockets.” In the dog-chasing-its-tail fashion of social media, he had tweeted about an earlier story by the magazine writer, who then contacted him for comment for the new piece.

He says social media is not universally accepted among scientists. “It’s hard to get academic credit for this,” says Jackson, adding that there’s a common perception that “if you’re tweeting and blogging, then you’re not doing science.”

In November, he will run a workshop session about taxonomy and social media called “The New Natural Historians” during the annual meeting of the Entomological Society of America. “We hope to get people to open their eyes to the potential of social media.”

Back in the insect collection, he is technical editor of the Canadian Journal of Arthropod Identification. That peer-reviewed, web-based journal was launched by Marshall in 2006.

Referring to social media, Marshall says, “This is one facet of the general phenomenon of ‘democratization’ of our science.”

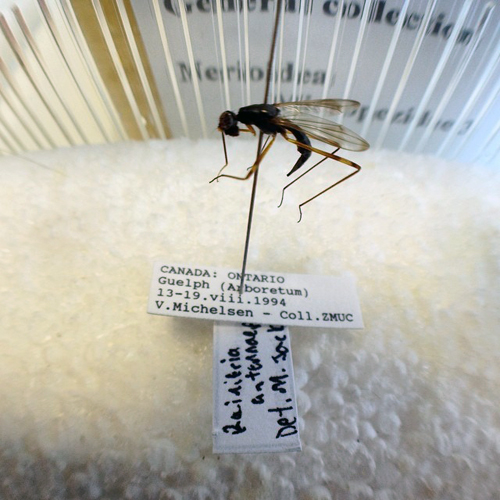

In the Bovey Building lab housing Guelph’s insect collection, Jackson spends a good portion of his days peering through the microscope at pinned specimens of stilt-legged flies.

Named for their long slender legs, this family of flies contains 700 to 800 species. Found worldwide, most live in the Neotropics; Jackson has visited Central and South America on collecting trips. Only a few species of stilt-legged flies live in southern Ontario.

Jackson hopes to help sort out which species is which. “Taxonomically, they’re kind of a mess. It’s hard to tell where a genus ends and begins.”

As an undergrad student at Guelph, Jackson was captivated by the creatures on photos shown in lectures by Marshall. That fascination endures, he says.

There are some 600,000 species of flies worldwide, including 150,000 named species. Only beetles are more diverse with some 250,000 known species.

He says he loves “the crazy diversity, the sheer number of insects, and the fact that you can go out and find new stuff all the time. It’s easy to make new discoveries. There are a lot of new species to be discovered and described.”