After feeling ill for about a year, Prof. Gary Grewal decided to visit his doctor. That decision turned out to be a lifesaver. “I feel like I’m going to die,” he told his doctor, referring to symptoms such as chronic fatigue and abdominal pain and swelling.

He was diagnosed in 2010 with hemochromatosis, a condition that causes the body to store too much iron. “I was feeling extremely ill,” says Grewal, a computer science professor. Blood tests revealed a high level of ferritin, a protein that stores unused iron. He was referred to a liver specialist, who diagnosed him with hemochromatosis, a genetic disorder.

Patients with the condition typically have more than one genetic mutation, but in Grewal’s case, one was enough to cause symptoms. Women usually begin to show symptoms at menopause, when their bodies stop losing blood through menstruation.

He began to monitor his condition using an Excel spreadsheet but later decided to develop an app that could help others with the condition. “I felt it would be useful to have a mobile app to keep track of my progress,” he says. “I had a sense of my own wellness.”

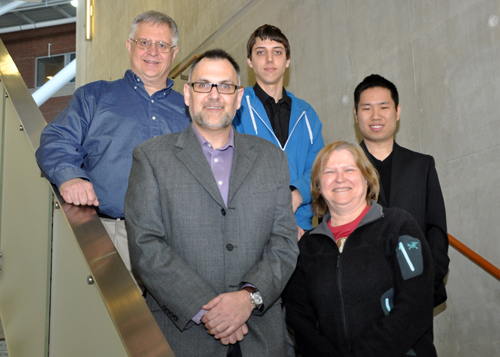

Grewal enlisted the help of two undergraduate students, Jiexin (Frank) Liu and Ryan Pattison, both in computer science. They partnered with the Canadian Hemochromatosis Society to create an app that helps patients monitor their treatment and helps raise awareness of a condition that affects one in 300 Canadians.

Without treatment, the body continues to store iron in organs such as the liver, pancreas and heart, eventually causing organ failure and death. Although Grewal is currently undergoing treatment, he says he has already sustained liver damage. Since the symptoms of hemochromatosis mimic other conditions, it often goes undiagnosed. “It’s one of the biggest failures of modern medicine,” he says.

Although there is no cure, the condition can be managed through a procedure called a phlebotomy, in which 500 millilitres of blood is drawn up to twice weekly to bring ferritin levels down. At that point, patients are considered to be in the maintenance phase and must undergo a blood test every two weeks to keep their ferritin in check. When ferritin levels begin to rise above the target of 50 nanograms per millilitre, another phlebotomy is required. Dietary changes can also help by reducing consumption of iron, found in red meat and fortified foods such as cereal.

“There’s nothing out there like this,” says Grewal of the app, which would help patients monitor their ferritin levels using a graph and predict when their target level will be reached. The app also helps patients keep track of their appointments and which arm was drawn from during their last phlebotomy.

Grewal plans to recruit 50 volunteers to test a prototype of the app before making it available to the public later this year.

Before Liu got involved in the project, he says he had never heard of hemochromatosis. “I might even have it,” he says, adding that a recent doctor’s visit revealed elevated ferritin levels.

Working on the app has given Liu experience that he says will be valuable when applying for jobs in the medical field. The students consulted with nurses and Canadian Blood Services staff to find out which features to include in the app.

Having reviewed other health apps, the students wanted to design an app that was user-friendly. “There’s no other help,” says Pattison, referring to its uniqueness among health apps. “It’s a need we’re trying to fill.”

Bob Rogers, CEO and executive director of the Canadian Hemochromatosis Society, visited U of G in March as part of a cross-Canada tour to raise awareness of the condition. “There are so many people suffering from this disorder who aren’t being diagnosed,” he says. “This app is one of the tools we’ll use to propagate awareness but also help people who have it. What you’re doing is great for us.”