Aaron Bowlby calls it his Sleep Class. That’s not the official name of the first-year seminar, but it gets people’s attention. “Everyone asks if we get to sleep in the course,” says the first-year music student at U of G.

So do they? No, says instructor Justine Tishinsky. “We ask that all students remain awake during classes.”

There’s plenty of reasons to stay awake in her new course, called “One-Third of Your Life Is Spent With Your Eyes Closed.” The seminar students are exploring why and how we sleep, modern stresses interfering with our rest, sleep disorders and dreams.

They’re also looking at ways to sleep better – no small thing for first-years getting used to a new lifestyle that might play havoc with normal diurnal patterns.

Whatever its exact purpose, sleep is necessary for us to stay healthy in physical, intellectual and emotional ways. Tishinsky says lack of sleep is associated with lowered academic performance, increased cardiovascular disease, auto accidents, stress, anxiety and depression.

“There’s convincing evidence that sleep is critical for learning. If you don’t get enough, your ability to process and remember is impaired.”

We’re generally getting less of it – or less of the good stuff. Most adults need seven to nine hours in a night. Besides quantity, quality of sleep matters. Normally we cycle through sleep stages each night, called rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM — or deep — sleep. Scientists believe the latter is especially important for regeneration of tissues and the immune system.

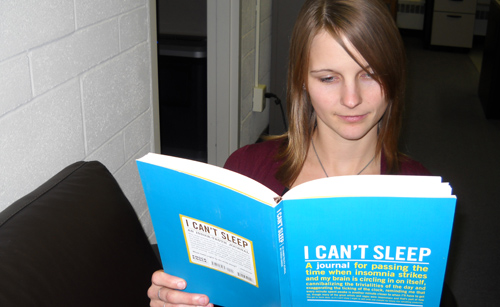

Insomnia rates are increasing, says Tishinsky. For culprits, look to modern-day stresses, notably imbalances among work, family and social pressures.

Technology is another problem. She blames electronic devices from e-readers to smartphones to TV. All emit light that interferes with normal circadian rhythms when they’re used just before bedtime.

Ideally, you should limit your light exposure before sleeping. But that’s not customary among the students in her class. It’s routine for them to lie in bed and scan Facebook. “Every single person in the class sleeps with their smartphone beside the bed. Most don’t turn it off at night.”

Her students are at an ideal age to learn about good and bad sleep habits, she says. As emerging adults, they’re developing their lifestyle, including choices that affect health.

Tishinsky can vouch for lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise.

She has suffered from insomnia all her life. “I’ve had trouble falling and staying asleep for as long as I can remember.”

The problem never affected her academic performance, including her PhD at Guelph spent studying fatty acids, metabolism and health. She learned to adapt to impaired concentration and other symptoms.

Today she follows a strict regimen of exercise, yoga and diet, including avoiding sugary foods and caffeine past mid-day. She does aerobic exercise early in the day, including visiting a fitness club five days a week.

Says Bowlby, “This course has actually provided some applicable means to improve my sleeping habits, and done so with surprising ease and limited lifestyle changes. Nearly every ailment or bodily function can be linked to sleep habits.”

The class has also discussed possible reasons for dreaming, including aiding in learning, Freudian messaging, processing daily events, purging useless information – or no purpose at all.

Or how about predicting events?

This past summer, arts and sciences student Dana Main was in Norway when she dreamt that her grandmother had died. The next day she learned from her mother that Grandma had died that very night. “I never had a dream of that intensity. I woke up and I knew she was gone,” says Main, who is pursuing minors in French and neuroscience.

They’ve looked at other sleep oddities, including the sleepless elite, or “short sleepers,” who function on only a few hours of sleep a night.

“The class opens up your eyes to things you would have never thought twice about,” says Amanda Manderson, criminal justice and public policy. She enjoys learning about the science of sleep as well as more unusual aspects of our nighttime regimen. “People don’t just sleepwalk, but it expands further to the most bizarre of emailing, eating and having sex (while sleeping).”

Tishinsky hopes students better appreciate the importance of shut-eye. “It’s amazing that we spend one-third of our lives sleeping and yet know so little about it.”

By day, she’s co-ordinator of “Biological Concepts of Health,” a first-year course offered by the Department of Human Health and Nutritional Sciences.