She was looking for feminism, but what she found was fashion – fashion with a substantial dose of Canadian nationalism mixed in.

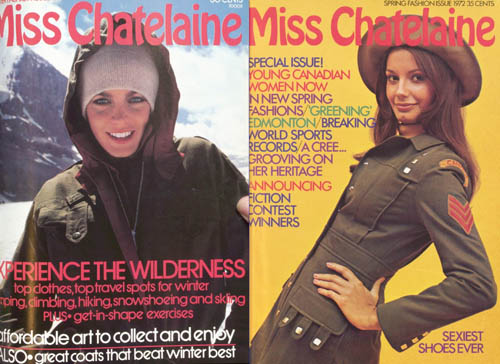

Recent U of G history grad Elizabeth Gagnon chose to study fashion in Miss Chatelaine magazine for her master’s research project “Looking Good, Looking Canadian.” It’s a short history compared to the publication’s influential parent: Chatelaine magazine, which has been published since 1928, was the inspiration for launching Miss Chatelaine in 1965.

“Miss Chatelaine was initially aimed at teens,” says Gagnon, who is currently working on a master’s degree in library and information science at Western University, “but by 1970 the target audience had shifted to young women in their 20s. In September 1979, the young Miss was rebranded as Flare: Canada’s Fashion Magazine.”

Chatelaine has been widely studied by historians, particularly for the way it influenced the growth of feminism in Canada. Gagnon expected to find much of the same in Miss Chatelaine. Instead, what she found was an emphasis on “being Canadian” that provides insights into Canadian national identity in the 1970s.

“I was asking myself, ‘Why are so many of the fashion shoots set in the outdoors? Why does the magazine have an annual ski fashion issue? Why are they making a point that these photos were taken in distinctly regional settings, like Newfoundland or Alberta?” Gagnon says the magazine was clearly interested in setting itself apart from American fashion magazines with bigger budgets that were its competition on the newsstands.

She adds: “They honed in on a number of prominent Canadian myths and stereotypes, suggesting that Canadians are unique because of our connection with nature and the wilderness and our cold weather.” In her paper, she writes: “In the fall 1977 issue, Miss Chatelaine’s fashion editor declared that the magazine was taking ‘a stand for the sort of dressing that best suits Canadians and their lifestyles.’ But what constituted a Canadian fashion look in the 1970s? The fashion editorial stressed that looking great the Canadian way meant looking warm yet ‘spectacular,’ since Canada’s fashion needs were dictated by ‘weather, weather and more weather.’”

One of the fashion articles declared “In Canada, we’ve got the weather, the wilds and the woollies to wear.”

Readers picked up and responded to the “we are Canadian” tone, writing letters to the editor with messages like these: “I enjoy Miss Chatelaine because it is Canadian, and I am proud to be one,” and, “Before I came to live in Kingston, I was pro-Quebec; now I am pro-Canadian. It is a great feeling, and Miss Chatelaine has a lot to do with it.”

The magazine also went beyond recognizable Canadian myths to emphasize new visions of Canada that included multiculturalism. Miss Chatelaine frequently featured models from various ethnic backgrounds at a time when most American magazines used predominantly white models in their fashion spreads.

“That was particularly true in the fall and campus fashion issues,” says Gagnon, “because often the models were actual university students from across Canada.”

The editors of the magazine also publicly stated that their goal was to have 70 per cent domestically-produced fashions in the publication’s glossy pages. “As a result,” explains Gagnon, “they focused on promoting a lot of Canadian designers, both more established ones and the up-and-comers. I think it had a significant impact on the Canadian fashion industry — one that hasn’t been adequately considered by historians.”

Well-known fashion designer Alfred Sung was regularly featured in Miss Chatelaine during the 1970s; he actually worked for the magazine as an illustrator and occasional feature writer.

Gagnon hopes other historians will take a look at this publication and what it can tell us about young Canadian women in the ’60s and ’70s. “I think there is so much more that can be learned from studying this magazine,” says Gagnon. “I was surprised that so little has been written about it. Miss Chatelaine was the first magazine to focus specifically on Canadian fashion, and it offers a lens through which to examine the rise of Canadian nationalism in the 1970s.”