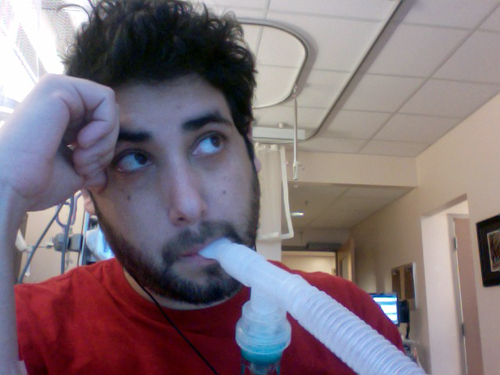

Jehangir Saleh was recently released from the hospital, but he knows it’s only a matter of time before he’ll be back. He was born with cystic fibrosis (CF), a condition that causes his lungs to fill with thick mucus, making it difficult for him to breathe.

The master’s student in philosophy isn’t just studying the philosophy of illness – he’s living it. Over the past four years, he has been admitted to St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto for several months at a time; his longest stay was five and a half months.

He was 20 when his condition worsened, shifting his perspective on life. He decided to switch his major from economics and human resources to philosophy. “Those things just don’t matter,” he says of his former major. “They’re pointless, to be honest. I was living in a hospital around people who were struggling to continue to live.”

The more time he spent in the hospital, the more he got to know his “neighbours.” Most of his hospital roommates were much older, he says, and they looked at him with pity. “They would sort of say to themselves, ‘Thank God I’m not him. It must be super ridiculously hard to be that age and to have a severe chronic illness that has a short life expectancy.’ But that’s now how I experienced it.”

Saleh decided to take a philosophical approach to his illness. “If God made the trees and the water and everything, then he also made cancer. If that’s true, then there must be something to learn from this. There must be some lessons, some aspect of human life that having an illness speaks to. I became interested in trying to figure those things out, mostly because I needed to figure out how to live with my own condition. I needed some sort of framework to understand what I was going through.”

Saleh compares living with cystic fibrosis to mopping a floor that keeps getting dirty. He goes through five hours of medical treatment and physiotherapy every day to help clear his lungs of “cement-like mucus” that harbours bacteria, causing chronic pneumonia. “It’s like a Holiday Inn for bacteria,” he says. His lungs produce about one cup of mucus daily, but his treatment loosens only about half that much for him to cough up.

The disease makes people more susceptible to pneumonia. Saleh has received constant intravenous antibiotics for the past three years. “In usual cases of CF,” he says, “someone gets an infection and goes to the hospital. They get some IVs for two weeks, they feel better and they’re stable for a while. In my case, once I’m off my IVs, I decline quite quickly.”

Cystic fibrosis also takes a toll on his friends and family. During his first few weeks in hospital, visitors brought flowers, chocolates and get-well cards to help him feel better. But when the weeks turned into months and it became apparent that he wasn’t going to get better, they ran out of gift ideas for the patient who has everything. But their support made “mopping the floor” more bearable, he says, and he learned how to live with his chronic illness instead of trying to fight it.

Spending long periods of time in the hospital also affects his studies. He is currently taking one course per semester. “I need accommodations,” he says. “I’m able to do the coursework, but at a different pace. I often need extra time to finish the course depending on what has happened to me health-wise during a particular semester.”

The degenerative nature of his disease will determine how long it takes him to complete his degree. “There’s only a finite number of antibiotics,” says Saleh. “What’s difficult now is not that my lungs are doing worse but that we’ve used all the possible treatment options, so now we’re just recycling them over again. That makes it more difficult to contain a flare-up when it occurs.” His lung function is about 60 per cent; it would need to be below 30 per cent for him to become eligible for a lung transplant.

One of the most difficult things about having cystic fibrosis, he says, is that it robs him of a normal student experience. “The real suffering occurs when people feel cut off from themselves.” When his health began to decline, he says, “I had spent the past three years working really hard finishing my undergraduate degree. My identity was really wrapped up in that project. I really wanted to write my exams. I really wanted to finish. Everyone else I knew was doing the same. I felt cut off from a part of the world that felt like home to me.”