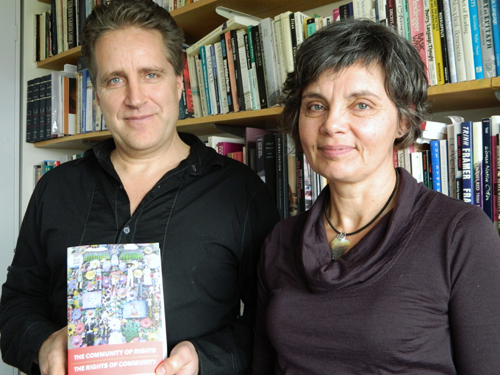

Occupy Toronto and related movements might learn something about creative yet practical forms of protest from protesters in other countries, say Guelph profs Daniel Fischlin and Martha Nandorfy. Faculty members in the School of English and Theatre Studies, they are co-authors of the newly published book The Community of Rights – The Rights of Community.

“We’ve seen in France and Mexico, for example, how quickly people took to the street to protest,” say the authors. “In Mexico, people set up community structures for blocks and blocks, and they had chess clubs and performance art going on in sync with the actual political protest. They were determined, but the protest didn’t limit itself to politics. It was a manifestation of real street community.”

And while the Occupy movement has been criticized for not having a clear agenda, Fischlin has no trouble figuring out the message. “What they are saying is ‘This is outrageous! We don’t know what has to happen to fix it, but we need to say that we’re not happy and this is not okay.’” The protest, he explains, is a response to events that began in 2008 when governments made massive transfers of public money to a very narrow group of elites. “Those people then gave themselves huge bonuses.”

The response from government, according to Nandorfy, is part of a strategy to disempower people. “They are trying to shut it down, challenging the right to public assembly.” But she says the right to public assembly is essential because it is an important assertion of community rights.

This same strategy was also visible at the G20 summit in Toronto where huge numbers of police were brought in to quickly end any attempt at legitimate assembly. “This happened even though the government leaders were never at risk,” points out Fischlin.

This spirited defence of rights by Fischlin and Nandorfy, and their insights into the links between rights and community, have grown out of a literary journey. The Community of Rights – The Rights of Community is the third book in a trilogy published by both Black Rose Books and Oxford University Press. The first was about Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano.

“It was neither a literary biography nor a book of criticism,” explains Fischlin. “We were looking at the full range of issues he deals with in his writing, including social justice and equity issues. Learning more about those led us to our second book, The Concise Guide to Global Human Rights. It’s a book that looks empirically at the big picture, using a wide range of social and scientific studies, as well as literary texts.”

Today, though, the term “human rights” sounds too linked to Western thinking that is anthropocentric and individualistic, says Nandorfy. “The focus in the past has been on the individual in terms of rights, rather than on the community. Yet we are all part of communities and are defined by our relations to others.”

Her definition of community is not based on people who are similar: “When people talk about something like the artistic community, that’s really a ghetto. A viable community is made up of people from all walks of life. You need to have tensions between people and ways to resolve the tension. Strong communities encounter diversity and learn from it.”

It is through these true communities, the authors contend, that the needs of individuals are best understood and met. Fischlin mentions that after New Orleans was hit hard by Hurricane Katrina, “the locals in some of the worst hit and poorest areas were often the first to respond directly to the crisis and make life-saving interventions to help people trapped by the flooding caused by the hurricane.” Communities tend to run below the surface until a crisis galvanizes the people to respond, he adds.

When rights are assigned to the individual, they ignore the idea that we are all interconnected, that we are all in relationships with each other as well as with the land and all living beings. “This is not dismissing the individual, but recognizing that we are all part of a bigger codependent and co-generative world,” says Fischlin.

In another example, the authors say missing that connection meant the UN Universal Declaration of Rights has some significant gaps, including environmental rights and cultural rights. “By leaving these out, it puts the responsibility on individuals to try to defend the environment and sustainability,” says Nandorfy. “It may well have been done deliberately because governments didn’t want to take on these responsibilities. But environmental rights are a fundamental precondition to all other rights.”

She and Fischlin say cultural rights are also important because we are all born into a web of connections, which is what culture is, so we cannot define ourselves purely as individuals.

Nandorfy points out that the First Nations communities with the healthiest populations are often those whose stories were maintained and/or recuperated from their attempted eradication by programs like the residential school system. This is because those stories tell people who they are as a community and connect them to the land in a spiritual and ethical relationship, which in turn fosters knowledge about how people should relate to each other and to all life. “Sometimes it’s about non-interference with culture,” she says, acknowledging that in some situations outside intervention, even if its aim is to help and develop, can be an extension of the “civilizing mission” driven by Eurocentric assumptions about the superiority of Western knowledge and technology.

“The true measure of rights is how we treat the poorest and most marginalized people. It’s not a matter of how we talk about their rights, but how those people actually live,” says Fischlin. Nandorfy adds that in international discussions, the wealthiest countries are the most resistant to having the right to food, water and other basic needs included in any charters.

The Community of Rights – The Rights of Community uses stories from many different cultures and data and research from around the world, analyzed by the authors to provide a new perspective on rights.

Early in the book, for example, they share the Parable of the Flute. Clara has made the flute, Anne is the only one who can play it, and Bob is a child who has no toys at all. They cite Indian economist and Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen, who says that the answer to the question of who should get the flute depends on political perspectives. Fischlin and Nandorfy, however, say that the question itself is wrong: “Why do we say one person should own the flute? Couldn’t it be shared? Why is Bob so poor he has no toys? Could Clara make more flutes? There are many possible resolutions when looked at from a community perspective.”

Adds Fischlin: Bringing community more fully into the rights discussion gives us vital new ways to interpret the world in a way consistent with American environmentalist Aldo Leopold’s view that “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”