Recent outbreaks of Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) in hospitals across southwestern Ontario have spurred concern about how to stop the spread of this deadly superbug.

University of Guelph PhD student Meredith Faires hopes her research will help stem C. difficile by identifying environmental factors that may be associated with C. difficile contamination in hospitals.

Evidence is increasing that the environment may play a role in the transmission of pathogens. The numerous spores formed by C. difficile resist most routine cleaning methods, making them difficult to eradicate. If contracted, the superbug can cause flu-like symptoms, severe diarrhea and, in some cases, severe colon infection. Seniors are the most vulnerable, but any hospital patient on broad-spectrum antibiotics is susceptible, as the drugs suppress good bacteria in the gut.

Faires studies C. difficile and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in smaller community health-care facilities in Ontario. Although these bacterial infections commonly occur in large urban hospitals and long-term care facilities, little is known about the frequency and severity of infections or the strains found in rural settings.

Right now, no one knows whether results from large studies conducted in large metropolitan hospitals apply equally to local hospitals across southwestern Ontario, said Faires, who earlier studied veterinary medicine.

“We still don’t know what difference, if any, demographics make, seasonality, or the frequency of occurrence outside the time frame of a so-called outbreak, or what strains of C. difficile, for example, typically develop in more rural communities compared with big cities. This information is important to properly assess and address the problem.”

Working with population medicine professor David Pearl and pathobiology professor Scott Weese, Faires is studying MRSA and C. difficile at the molecular, patient, environment and hospital levels. She began her study 18 months ago, visiting four regional hospitals once a week for four hours at a time.

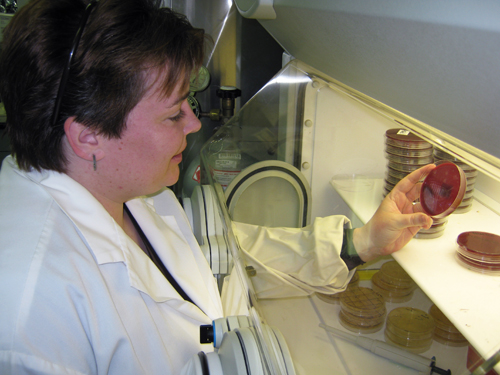

She used sterile cloths to wipe a variety of surfaces — countertops, patient charts, handrails, sofas and cork boards — in surgical and medical wards, nursing stations, visiting rooms, patient rooms and hallways. She then examined the samples in the lab and will compare them with samples from infected patients to determine which strains are popping up in community hospitals.

Faires, who recently won a Canadian College of Microbiologists award for a poster presentation on her research, hopes her study can identify specific risk factors, such as when and where these bacteria will most likely be found. She also hopes to help further define more practical protocols and procedures for infection prevention and control in community health-care facilities.

“The patients, nurses and cleaning staff I’ve been working with have been extremely positive and co-operative,” she said. “They want to find out the results just as much as I do, so they can figure out how to apply them and control any incidents of C. difficile and MRSA better.”

In a second study, Faires is examining health records from eight community hospitals in Ontario to determine whether certain areas in the facilities are more prone to harbouring the superbug and whether occurrences of C. difficile and MRSA are linked.

“I’ll compare my patient specimens and data with known outbreak records. The outcome of this study should help hospitals analyze their own data and potentially redefine their outbreaks. Hopefully, we’ll soon be able to identify them faster and more accurately.”