Story by Marisa Catapang, a U of G student writer with SPARK (Students Promoting Awareness of Research Knowledge)

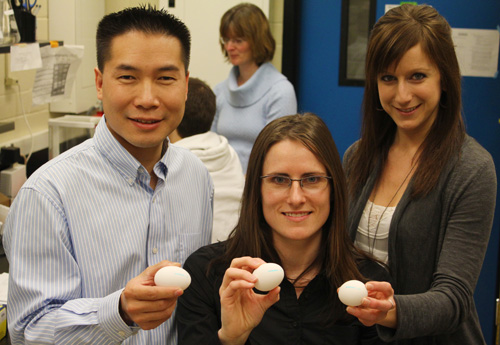

Starting early in life with a steady diet of omega-3 fatty acids could be key to reducing breast cancer, say Prof. David Ma, and graduate students Mira MacLennan and Breanne Anderson, Human Health and Nutritional Sciences.

Their early research results show that exposing mice to omega-3 fatty acids ─ even before they’re born ─ decreases the size and number of breast cancer tumors by about 20 per cent in adult mice. This research supports a growing body of data indicating that exposing embryos, babies and toddlers to certain nutrients can influence chronic disease later in life.

“What you eat as a child, or actually even earlier, what your mother ate, can have a profound impact on your risk of developing certain chronic diseases,” says Ma.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in Canadian women and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths. It is different from most cancers because breast tissue development, unlike other tissues, is incomplete at birth.

Previous breast cancer studies have not accounted for what happens during early life and early breast development. Therefore, they’re “missing a big part of the puzzle,” says Ma.

Typically, breast tissue undergoes continuous development from birth to first pregnancy, when full maturation of the breast finally occurs in preparation for lactation.

During development, breast tissue undergoes several critical growth periods when it is particularly vulnerable to mutations. Each of these growth periods represents a window of opportunity for various environmental factors, including diet, to influence the risk of breast cancer.

The Guelph study was jointly funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Breast Cancer Research Alliance, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, and the Ontario Research Fund. Anderson received additional support through a graduate fellowship from the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation ─ Ontario Region, MacLennan from a Canadian Institutes of Health Research M.Sc. award.

The exact mechanism by which omega-3 fatty acids inhibit breast cancer growth is unclear, but preliminary results from their study suggest ensuring a continuous supply during each critical growth period may be important for prevention. Ma says the best strategy may be to consider omega-3 fatty acids as a long-term investment. “By contributing a little bit over time, you have that added compounded benefit.”

Unfortunately, given Canadians’ inadequate omega-3 intake, the first priority should be to increase omega-3 fatty acids in the diet, he adds. This can be achieved by consuming a variety of foods and supplements rich in omega-3, including flaxseeds, walnuts, certain vegetable oils, fish and fish oils.

Milk and eggs fortified with DHA, a type of omega-3 fatty acid, are also available, thanks to previous U of G research.

As promising as these early results may sound, Ma cautions about over-interpreting the effects of food, particularly after the onset of breast cancer. “There will be a point in time when diet may have no beneficial impact in terms of disease treatment, and that’s where drugs come into play,” he says. But until that point, he adds, diet can make meaningful contributions toward disease prevention.

These findings were presented at the 2010 International Symposium on Breast Cancer Prevention, hosted by Purdue University. They will also be presented at the upcoming 2011 Canadian Nutrition Society annual general meeting, co-chaired by Ma and hosted by the University of Guelph June 2 to 4.