Larissa Lai was in Hong Kong with fellow poet Rita Wong for the Hong Kong International Literary Festival when two global crises hit: the United States invaded Iraq, and the SARS investigation determined that Hong Kong was ground zero for the disease.

“Hong Kong is usually bustling with people and energy, but the streets were almost empty,” Lai says. “More than half of the writers expected to present at the festival cancelled. After festival sessions, we’d go out and walk around the deserted streets. When we came in, we’d watch the U.S. invasion of Iraq on TV. We both felt very depressed.”

How do poets cope with a depressing and surreal situation? They write poetry, of course. “Rita had a notebook, and we each wrote in it and passed it back and forth,” recalls Lai. “It helped.”

That poetry never became public, but after they returned to Canada, Lai and Wong heard a poetry reading where Aaron Vidaver and David Fujino read a poem they had written together. “It reminded us of the poetry we’d written in Hong Kong, so we decided to try it again, and it turned out to be fun. We used the poem to play with language, to talk about our lives, and to talk about what was going on in the world.” That collaborative work became the book Sybil Unrest.

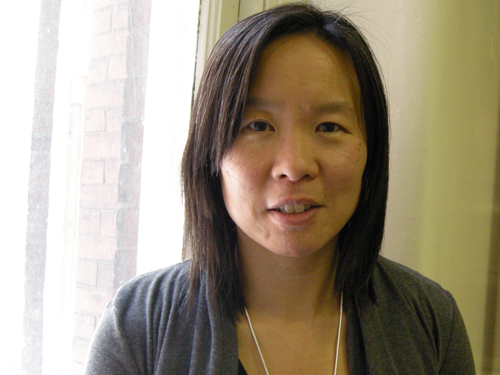

Lai is this term’s writer-in-residence at U of G, and she’s enthusiastic about sharing the lessons she has learned in writing poetry and novels with members of the Guelph community. Those interested in working with her should make an appointment to leave up to ten pages of their writing with her; she’ll provide “straight-forward feedback.”

That means you’ll get the truth. “Don’t expect to be patted on the head and told that you’re a genius,” Lai adds. “I’ll give honest, critical feedback that you can use and make your work better. I expect people to be serious about their writing.”

Lai was born in California but grew up in Newfoundland until her last year of high school, when she moved to Victoria, B.C. She attended the University of British Columbia as an undergrad and then found work as the assistant curator for “Yellow Peril: Reconsidered,” a travelling exhibition of film, video and photo-based work by Asian Canadian artists. “Working on that introduced me to a broad arts community and opened doors for me to do a lot of cultural organizing and arts reviewing,” she says. Lai also began writing, producing a novel called When Fox is a Thousand that was shortlisted for the Books in Canada First Novel Award. Later she wrote a second successful novel, Salt Fish Girl, and two books of poetry, Automaton Biographies and Sybil Unrest with Rita Wong.

Lai says she was greatly encouraged by writer Shani Mootoo, who was the U of G’s previous writer-in-residence. “Three of us (Mootoo, Lai and Monika Kin Gagnon) used to meet in Shani’s apartment above a beauty salon. Shani would feed us, and we’d show one another bits of writing. We talked about politics as much as we talked about writing, I think, but there was so much support and engagement around that table.”

In 1999, Lai returned to university and did her MA at the University of East Anglia, followed by her PhD at the University of Calgary. She’s now a professor at the University of British Columbia and says she finds the work enjoyable but demanding. She is looking forward to having time to write.

“My experience is that when I’m writing well, I write quickly,” says Lai. “But I have to drink a lot of tea and think and walk around to get to that point.”

Not just thinking. Lai does a considerable amount of preparation for novels.

“There is a lot of preliminary work to lay out the plot, and while I’m doing that I am also working out character and setting. For instance, when I am thinking about plot, I invariably have to think about conflict, which means I am already thinking about character. But I also make notes as ideas or fragments of larger pictures occur to me. Sometimes that means bits of back story or over-arching structure; sometimes it means a character quirk or a snippet of setting. I make files for characters, files for the back story, files for the plotting,” she says.

“Because I do speculative fiction, I also have to have files about how various technologies, real and made up, work. I’m inventing technology, so if I’m not careful I’ll end up having it work in different ways in different parts of the novel. That can require a lot of revision, because often something that seems small and not too important in the beginning ends up having big repercussions later. Then of course, I also have a file where the actual novel is unfolding. Invariably, the first draft is no good. I draft and redraft. When it gets closer to done, sometimes I still need to make changes in one area that then necessitate adjustments elsewhere so it will all hold together.”

Because her novels take a speculative fiction bent, she will also “do a lot of world-building stuff, both before I start and as I go along. I’m always going back and forth between the files that define and describe the world of the book, and the actual text of the novel. I also have material on the relationship between the imagined world and the real world ─ a fake history about how the imagined world came to be. The preliminary stuff exceeds the word count of the novel by a ratio of at least five to one.”

While working with writers at U of G, Lai is also writing a new novel. “When I was working on my PhD, I also wrote about 300 pages of a novel, but it’s very rough. I realized the novel had a back story, and I started writing that, and it turned out to be a prequel. Last year I got about a third of it done. I’m excited about having this chunk of time to continue work on it.”

She hopes that while she’s been teaching, her subconscious will have been working away on the novel. “In some ways, writers are helpless, at the mercy of the muse or the gods or whatever you want to call the collective, impersonal source from which creative work comes. It definitely feels as though the work comes from somewhere else.” But Lai doesn’t let that sense of helplessness keep her from putting words on paper. “A big part of writing for me is showing up. I get up in the morning, show up at my desk and see what’s there. I may have no idea at all what I’m going to write when I sit down. Sometimes I’m just bashing away at the narrative, trying to push the story forward.”