For PhD student Melanie Wills, science is woven into her DNA. Take the time she helped her dad and uncle — both among a long line of engineers and scientists on her paternal side — to free a car stuck at the bottom of a hill. While the men prepared to push, she slipped behind the wheel.

“As I was gearing up for the run, my dad said: ‘Remember, the coefficient of static friction is higher than the coefficient of dynamic friction.’”

Smiling years later at the recollection, Wills translates. “That meant: ‘Don’t spin the tires.’” Did it work? Another smile: “On the first try.”

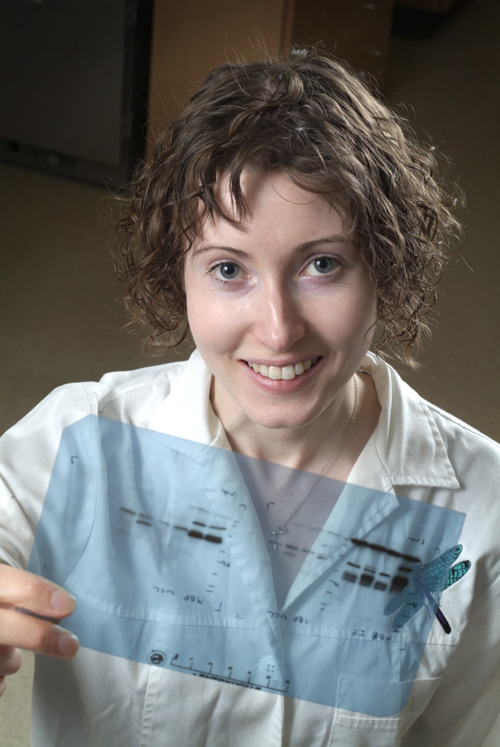

If her doctorate is a new hill to climb, she’s just gotten some extra traction. Wills has received U of G’s most prestigious graduate award to pursue research in cell signalling and cancer, interests she developed during undergraduate lab studies with Prof. Nina Jones, Molecular and Cellular Biology, now her PhD supervisor.

The Brock Doctoral Scholarship — worth up to $120,000 over four years — is awarded to an entering doctoral student considered outstanding in his or her field and able to lead other students in their own PhD programs.

The award is funded from a $10-million endowment donated to U of G by Bill and Anne Brock. Bill Brock is a 1958 graduate of the Ontario Agricultural College and a former chair of Board of Governors and the Board of Trustees.

“The Brock scholarship recognizes the potential of this research,” says Wills. “It lights a fire under you and keeps you going.”

Jones says her student brings both research and communication strengths to her lab.

“She is an absolutely outstanding individual, committed to her academic and extracurricular pursuits, and directing a cutting-edge research project with her own ideas, curiosity and integrity.”

They study how cells communicate through so-called Shc proteins. Within that family, Wills is looking at the ShcD protein that enables communication between brain cells and between skeletal muscle cells.

That molecule was found by Jones, then a post-doc, and other scientists at Toronto’s Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute. It’s involved in relaying signals allowing the brain and skeletal muscles to function.

“Not much is known about it,” says Wills, who hopes to learn more about how and why the protein works and what happens when it malfunctions.

Shc proteins are involved in cell development and maturation, including determining when cells continue or stop dividing. “It’s part of the decision process,” she says.

When that decision-making process goes awry, cancer can occur, allowing cells to basically run amok or even migrate in the body to start tumours in other tissues.

Last year, Wills and Jones co-authored a grant application that yielded new funding from the Brain Tumour Foundation of Canada.

Wills hopes studying signal pathways will ultimately help clinicians design trials for human patients.

“We’re trying to provide information that, down the road, would help people in clinical settings to develop diagnostic markers.”

Signal transduction allows a cell to collect information, analyze that data and respond. To grasp the idea, she says, think of how you might respond to learning about a burger sale at your favourite restaurant.

“You integrate that information with your hunger level, your desire for a burger and the change in your pocket, and decide whether you’re going to buy a Whopper.”

Now imagine a single cell having to make sense of the “advertisements” in its own world. “We’re not talking about huge organisms. It’s one simple unit that has to receive information and act on that. How does a single cell act as an entire organism would?”

Wills grew up in Lindsay and arrived at U of G as a 2003 President’s Scholar. Now living in Guelph, she is a co-organizer of the SharpCuts independent film and music festival, which runs May 5 to 9.

Past festivals have screened her documentaries blending art and science. Five Degrees looked at undergraduate students striving to become scientists in Guelph labs. Wills has also filmed two documentaries about retired integrative biology professor Doug Larson.

In addition, she produced Not Quite Famous, a show that focused on her mother’s career as a self-published author of historical novels.

Wills began exploring multimedia at age 14 as a producer and co-host of a community TV program for teens. Today she runs a production company called Double Helix Creations, a nod to the structure of DNA.

Merging film and science in another way, she completed a 10-minute short about an experimental procedure in Jones’s lab submitted last month to the online Journal of Visualized Experiments.

“The blending of art and science brings the concept of research communications into an exciting new place,” says Jones.