Outside, it’s a grey fall day, but indoors, it’s still green, thanks to a bit of U of G technology transplanted to the new University of Guelph-Humber Building in Toronto.

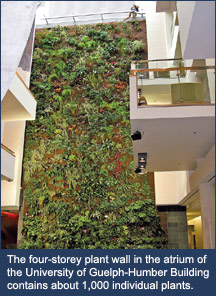

That eye-catching “plant wall” extending from top to bottom at one end of the four-storey building’s atrium will provide lush relief year-round. Beyond esthetics, the biofilter will help clean and freshen the air in the building, and is expected to help reduce the school’s air-conditioning bill.

So says Alan Darlington, a multiple degree-holder from U of G and president of Air Quality Solutions Ltd. based in Guelph. Using seed technology developed at the University, his four-year-old company designed and now maintains the 150-square-metre wall with its roughly 1,000 individual plants installed early this year.

So says Alan Darlington, a multiple degree-holder from U of G and president of Air Quality Solutions Ltd. based in Guelph. Using seed technology developed at the University, his four-year-old company designed and now maintains the 150-square-metre wall with its roughly 1,000 individual plants installed early this year.

Standing atop the spiral staircase at the south end of the atrium, Darlington looks directly across at the building’s signature plant wall and says, “It’s basically vertical hydroponics.”

If you asked a landscape gardener to design an indoor wall mural, you might get something resembling the new “green machine” at Guelph-Humber. Plants have been rooted artfully from top to bottom, tucked into blocks of a synthetic rooting medium mounted on a metal support frame designed along with the building’s architects, Diamond and Schmitt Architects Inc. of Toronto. From a pool at the base of the wall filled with lava rock, water is pumped upward to percolate back down through the material and carry nutrients to the plant roots.

Even on a recent overcast and rainy day, the south-facing wall receives plenty of natural light through overhead skylights. In addition, a pair of lights is suspended from balcony seating areas within view of the wall; identical balconies overlook the wall on every floor of the building.

Closer to the skylights are such species as geraniums, hibiscus, fuchsia and ivies. Nearer the floor grow more shade-tolerant plants such as spider plants and philodendrons.

Using plants’ natural respiratory properties, the living wall is intended to cool the building air in summer and work like a humidifier in winter.

Equally important, the closed system is designed to remove compounds that have been shown to contribute to poor indoor air quality. Natural processes carried out by the microbes living on and in the plant roots break down these volatile organic compounds as air is drawn through the system.

Research at U of G has shown that the system can remove half of the benzene and toluene in the air during a single pass and up to 90 per cent of the formaldehyde.

These substances are known to contribute to “sick building syndrome,” a problem that contributes to employee absenteeism in office buildings around the world. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says about one-third of absenteeism due to illness stems from poor air quality. One European study showed that greening indoor space can reduce worker absenteeism by 15 per cent.

Darlington expects to begin demonstrating and recording those effects when he turns on the system’s air intake fans later this fall. Working with researchers in the Department of Environmental Biology and the College of Social and Applied Human Sciences, he plans to test the plant wall’s impact on occupants’ well-being.

He will also work with the Humber Arboretum on a project to compare operation of the “living wall” with more traditional systems planned for a proposed Centre for Urban Ecology to be built at Humber.

The plant wall grew out of a decade’s worth of research at Guelph led by Darlington’s graduate supervisor, Prof. Mike Dixon, now chair of the Department of Environmental Biology. Using variable-pressure chambers in the Bovey Building, Dixon studies the use of plants for closed systems on Earth and in space.

“The methods he uses for life on Mars are largely the same ones I use for life in downtown Toronto,” says Darlington.

He and Dixon started studying biofiltration systems in 1993 on a plant wall installed at the Canada Life Assurance Building in downtown Toronto. Recalling his after-hours experiments on the wall, Darlington says: “As far as I was concerned, it was a research facility, and as far as the company was concerned, it was a boardroom.”

The Guelph-Humber plant wall is the fourth installation — and by far the largest — that Darlington’s company has completed in the past year. Biofilter walls are also operating at Queen’s University, at the headquarters of the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority and in the Richardson Building, a private office in downtown Toronto.

Back at Guelph, Dixon is now applying his expertise in biofiltration in a $1-million three-year project to improve air quality in animal holding facilities. Working with U of G faculty in the School of Engineering and the Department of Animal and Poultry Science, he is developing air- handling systems to remove ammonia and use microbes to make nitrate for growing plants. Those plants might then be fed back to pigs or collected for use in fertilizer.