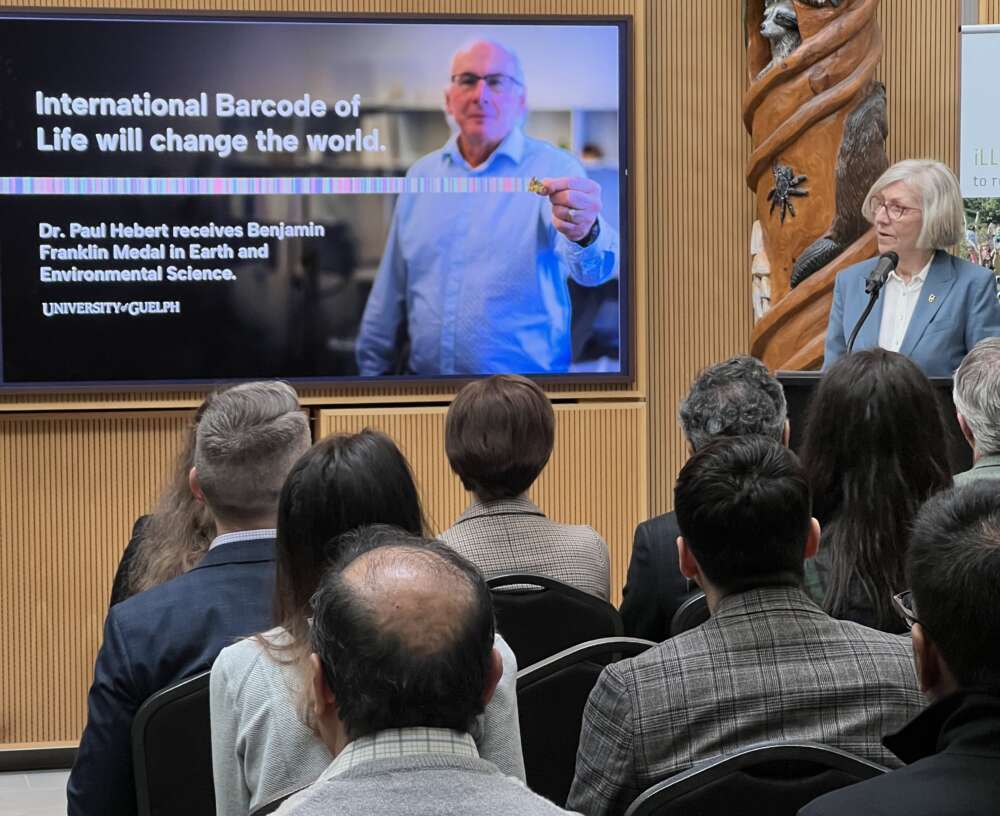

On March 14, about 150 members of the University of Guelph and the community gathered at the Centre for Biodiversity Genomics (CBG) to celebrate the remarkable global contribution of Dr. Paul Hebert and the Centre. Hebert developed DNA barcoding, which can identify millions of animals on the planet using a short segment of DNA.

Known as “the father of DNA barcoding,” Hebert was recently awarded the Benjamin Franklin Medal for Earth and Environmental Science. As a recipient of the medal, Hebert joins the ranks of past laureates who include Nikola Tesla, Albert Einstein, and both Marie and Pierre Curie.

Building on Hebert’s foundation of DNA barcoding, the CBG now houses the world’s largest DNA bank for biodiversity with DNA extracts from 10 million specimens. It also has developed BOLD, the informatics platform that currently holds sequences from 16 million specimens with three million new records added annually.

The largest DNA bank for biodiversity has global impact

At the event, Dr. Charlotte Yates, U of G president and vice-chancellor; Lloyd Longfield, MP for Guelph; Dr. Rene Van Acker, interim vice-president research; and Dr. Mazyar Fallah, dean of the College of Biological Science, reflected on the significance of the work and the impact it has on the world.

“The work of Dr. Paul Hebert and other incredible researchers at the College of Biological Sciences is certainly a shining example of the global impact of our esteemed faculty members and of our global partnerships,” said Yates. “Dr. Hebert’s work in DNA barcoding is truly ground-breaking and enables scientists around the world, including community scientists, not just those who are within the halls of the university, to catalogue new species more quickly and effectively.”

“The impacts of DNA barcoding have had ripple effects far beyond the goal of cataloguing life of course,” said Dr. Mazyar Fallah, professor and dean of the College of Biological Science. “One if its biggest uses is in environmental and conservation science. Environmental DNA can give biologists a sense of the species living in an environment using only a small sample of water, soil, or even air.”

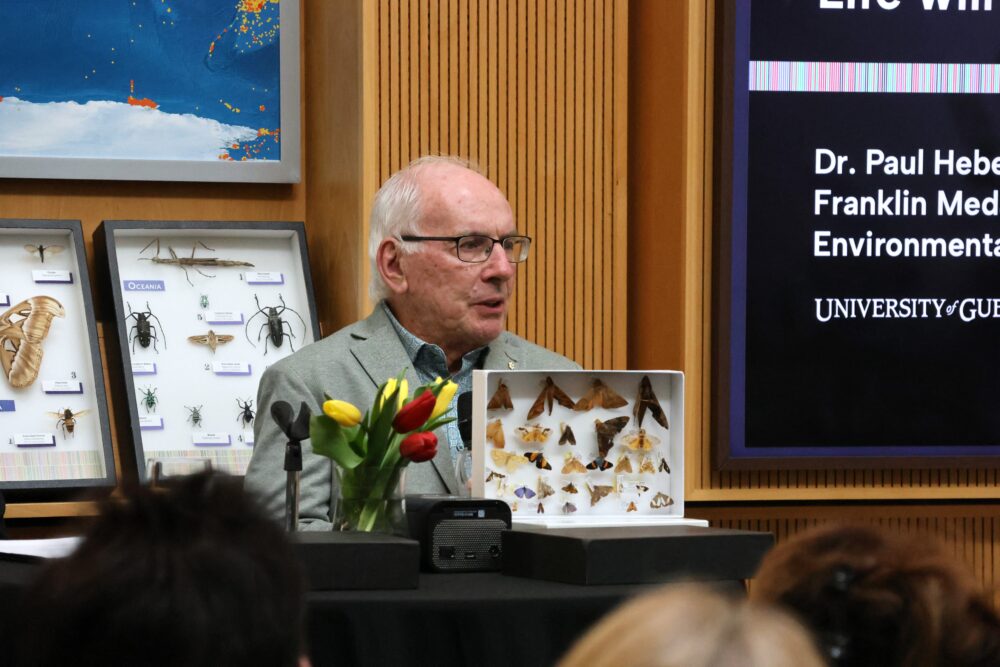

Addressing the attendees that included Hebert’s family, peers, current and former students, researchers, local politicians, and university staff, Hebert was quick to acknowledge the team behind him. “People win these awards for a variety of reasons,” said Hebert. “Some people, like Einstein are clearly ‘the Picassos of science’ I think other individuals, and I certainly place myself in this category, are being recognized not for individual accomplishment but for group accomplishment… That’s the power of science, [it’s] not the individual effort that accomplishes the really big things, it’s almost always group effort.”

From the past to the future of DNA barcoding

After initial remarks, Hebert captivated with the story of how he came up with DNA barcoding, showing preserved specimens of the moths that had originally inspired his interest in evolutionary biology as a boy. He also brought out a handheld DNA sequencer, PromethION, that can gather 250 million barcode records a year at a cost of just a tenth of a cent per specimen.

Looking to the future, Hebert shared his hopes to catalogue all life on Earth powered by the capabilities of new technology through the not-for-profit International Barcode of Life consortium, headquartered in Guelph. The applications of building this comprehensive catalogue of life are immense, from analyzing the impact of human activity on biodiversity to tracking shifts into the genetic makeup of entire ecosystems.

For Hebert, gathering biodiversity data is just the start. “Having data is not the same as driving societal change,” said Hebert. “We’ve recently expanded our DNA work by using sensors to listen to organisms and to watch them, delivering a comprehensive view of our impacts on biodiversity, but how do we translate this information into public policy? I think we have to broaden that tent, engage more people to move from biomonitoring to societal change.”

Hebert’s students carry on spirit of curiosity and collaboration

Two of Hebert’s former students, Dr. Beth Clare and Dr. Kara Layton, joined the event to share how working with Hebert influenced their approach to research and leadership.

“I think what I’ve learned most is just a genuine interest in natural history, an appreciation for the biology and ecology of the organisms I was interested in,” said Layton, assistant professor at U of G Mississauga. “I found myself in Antarctica, Columbia, these places where I’ve been able to work with incredible communities of researchers trying to use DNA barcoding to understand more about the diversity of life.”

“The thing I learned from my five years here was there was a lot of creativity that you could do in science,” said Clare, associate professor at York University. “Let graduate students try stuff, because sometimes it’ll work. You’ve got to be a little bit risky to do something that’s important.”

Congratulations to everyone at CBG and those who have had a hand in this amazing achievement and testament to U of G’s commitment to sustainability and global impact.