A new digital resource co-hosted by the University of Guelph will celebrate and develop the growing movement of Indigenous conservation and to inspire further conservation initiatives.

The IPCA Knowledge Basket launched last month provides information and guidance to support Indigenous governments and conservation groups as they implement their visions of conservation on the lands and waters in their traditional territories.

The online platform was created by the Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership (CRP), an Indigenous-led network that brings together Indigenous community leaders, environmental organizations and academia to advance Indigenous-led conservation.

The University of Guelph is one of three organizations co-hosting the CRP, along with the IISAAK OLAM Foundation and the Indigenous Leadership Initiative. The University of Guelph oversees the research undertaken by the partnership and provides administrative support. Dr. Robin Roth, a professor in the College of Social and Applied Human Sciences, is the CRP’s principal investigator.

The interactive site brings together the largest collection of information on the creation of Indigenous-led Protected and Conserved Areas, or IPCAs, which are lands and waters where Indigenous Peoples have made a long-term commitment to conservation for future generations.

It offers a searchable database of resources and illustrated guide for creating IPCAs, a growing collection of stories from Indigenous-led conservation initiatives, and links to more than 1,000 academic and non-academic resources.

Visitors to the site are encouraged to browse and gather resources based on their interests and needs and place them in their own “basket,” while contributing resources of their own.

‘Science doesn’t have all the solutions; Indigenous Peoples have valuable knowledge to share’

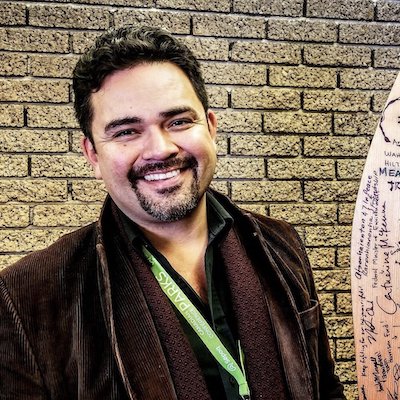

Eli Enns says the IPCA Knowledge Basket was designed “through a two-eyed seeing lens,” to bring together the best of Indigenous knowledge systems and Western science.

Enns is a Nuu-chah-nulth expert in biocultural heritage, one of the Indigenous leads for the CRP and the co-founder of the Indigenous educational not-for-profit IISAAK OLAM Foundation.

Over the last 20 years, Enns says he has witnessed the slow recognition among settler populations that Indigenous Peoples have valuable knowledge about ecosystem stewardship, as well as legal authority to create protected areas through their own legal systems.

“Part of what has driven that recognition and the embracing of Indigenous knowledge by the scientific community is climate change, and the recognition that science doesn’t have all the solutions and that Indigenous Peoples have valuable knowledge to share,” Enns said. “That’s been a major paradigm shift.”

With the federal government vowing to protect 30 per cent of its land by 2030, Enns says governments have finally accepted they will need to work with Indigenous Peoples in Canada to meet these goals.

IPCAs are key to doing that, providing a promising future for conservation and reconciliation.

Indigenous governments determining IPCA management

In an IPCA, Indigenous governments lead in determining their management and boundaries, although many also form partnerships with Crown governments, environmental NGOs and others to support their goals.

Enns says one aspect that distinguishes IPCAs from national or provincial parks is the focus on creating sustainable livelihoods and economies within the lands and waters.

“Most national parks were created solely for visitor recreation. Ecological integrity was not even introduced as a management priority until much more recently,” said Enns.

These parks were mostly created without the consent of Indigenous Peoples, who were often ordered to leave and abandon their cultural practices on the territory.

An IPCA looks at human social systems as a part of the environment that forms a relationship with the land, in that whatever is taken from the land is also given back in the spirit of reciprocity, he said.

Numerous studies have shown Indigenous-managed lands are as or more effective in preserving biodiversity than state-led conservation areas. What’s more, they represent vital pathways to Indigenous self-determination and cultural revitalization.

While dozens more IPCAS are currently in development within Canada, they form a part of a relatively new landscape. The IPCA Knowledge Basket is a much-needed resource to help navigate this landscape, said Enns.

“The knowledge basket will continue to grow over time. It’s designed to be a living resource, a place to bring the best of Indigenous knowledge and Western science and modern technology together to solve problems through a two-eyed seeing approach.”

Other financial contributors to the project include the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the David Suzuki Foundation, Ducks Unlimited Canada and World Wildlife Fund Canada.

The IPCA Knowledge Basket is one of three legacy initiatives of the CRP. The next initiative has already begun: a network of IPCA Innovation Centres across Canada, the first of which has just launched in British Columbia called the Clayoquot Campus. A third initiative, called the IPCA Alliance or Network, is in the works to continue to support Indigenous-led conservation beyond the CRP.

Contact:

Kristy Tomkinson, Communications and Knowledge Mobilization Specialist

Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership

tomkinso@uoguelph.ca