America will only become a fairer nation once its warring political factions gain a deeper understanding of each other’s concept of justice, says University of Guelph psychology professor Dan Meegan.

Meegan discussed his new book with TVO’s The Agenda. He also contributed a commentary to The Atlantic.

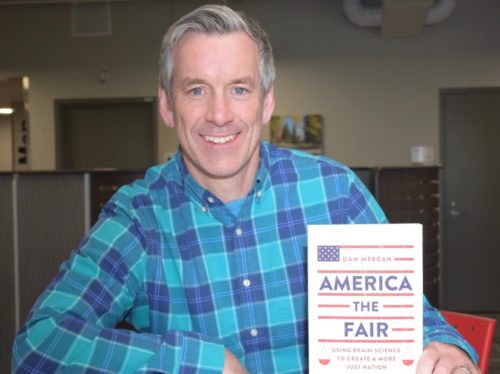

Human beings are hardwired to recognize and react to injustice, but not everyone reacts to it for the same reasons, he said. An expert in the psychology of fairness, Meegan is the author of the new book, America the Fair: Using Brain Science to Create a More Just Nation (Cornell University Press). It is scheduled for release on April 15.

“The main theme of the book is that different people have different conceptions of what’s fair and what’s not fair,” said Meegan.

When our “That’s not fair!” button is pushed, we can turn our ire on our fellow citizens, seeing them as competitors. But Meegan’s book suggests it is often in our best interest to see others as potential cooperative partners.

In the book, Meegan — originally from Rochester, New York, and a self-described liberal — explores ways in which liberals and conservatives see the world through a different justice lens. Liberals would be more successful at getting their policies enacted if they considered the conservative perspective, he writes.

In American politics, liberals and conservatives see the suffering of others through opposing values, Meegan said. Liberals tend to view social justice, and therefore social policy, as a matter of what is best for those who are less fortunate. Conservatives consider first the impact on “what is good for me.”

A liberal will more readily see suffering as an outcome of societal conditions, while a conservative will see it as a matter of poor choices.

The clash of differing opinion and lack of mutual understanding throw up roadblocks to progressive policies and can lead to political stalemate, Meegan said. He believes there is a solution that involves acquiring a basic understanding of and appreciation for the values of others.

While concern for the well-being of the less fortunate may be more altruistic than self-interest, both are relevant, he said. It is reasonable to be concerned about whether a new social program or taxation measure will benefit you and your immediate family.

“What’s striking to me is that both sides are kind of remarkably unaware of how the other side feels about this particular issue of fairness,” he said.

Whether we think policies should protect the have-nots or the rights of individuals, Meegan believes there is a middle ground – a way of blending the two perspectives so that progressive policies that protect everyone in areas like public health care or social security can more easily be accomplished. In turn, society would become fairer.

“The aim is to try to teach both sides what the other side thinks of this issue, and knowing there is this difference between them, trying to find policies that satisfy both definitions,” he said.

The fairness instincts of human beings were formed ages ago, when our ancestors lived in small, tight-knit groups and when the fair distribution of resources was essential for personal survival, Meegan said.

“Humans have visceral reactions to unfair treatment, but generally we are much more sensitive to injustices that occur to us personally than we are to those that happen to others.”

Contact:

Prof. Dan Meegan

dmeegan@uoguelph.ca