When a deadly assault on young women unfolded 29 years ago at École Polytechnique in Montreal, Karina McInnis was an engineering student in a lecture hall at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont. She was terrified.

“I remember thinking that if someone came in behind us with a machine gun, we would all be stuck in there, defenceless,” said McInnis, a professional engineer who joined the University of Guelph as associate vice-president (research services) this year. “There was no way out. It was a terrible feeling.”

Prof. Mary Wells was in the early stages of her career in engineering, living in Hamilton, Ont., when the massacre happened on Dec. 6, 1989.

“I remember that day very distinctly,” said Wells, now dean of the College of Engineering and Physical Sciences. “It’s one of those moments in time when your emotions are so strong that the details are embedded in your memory forever.”

Prof. Soha Moussa heard early reports of the Montreal massacre while preparing to return home to Canada from Egypt as a recent engineering graduate of the American University in Cairo.

“Before we travelled, this was all over the news, all around the world,” Moussa said. “And my husband said, ‘Tell me why I would want to take you back there?’ I was a female engineer, about to start a master’s degree in a francophone university in Canada. It was frightening.”

The day that saw the murder of 14 young women – 12 of them engineering students – changed countless lives forever. It is commemorated each year as the National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women.

“These were my sisters,” said Moussa, now a professor of mechanical engineering at the University. “They were my age group. They were in the same stage of life I was. They were the trailblazers who were going against society to be what they wanted to be.”

Ten other women and four men were wounded in an assault that lasted 20 minutes. Others – collectively thought of as the “15th victim” – were unable to live with the nightmarish memories and emotional trauma of the event and took their own lives.

“Being a female in engineering at that time wasn’t easy,” said Moussa, who began her studies in New Brunswick. “When I started in first year, we were a class of 114, among whom were four girls. By second year, there were only two of us. We were few and far between. To lose so many like that, for doing what we loved, was just very hard for everyone.”

Listen to CBC Radio interviews with Prof. Moussa and Prof. Wells on Dec. 6

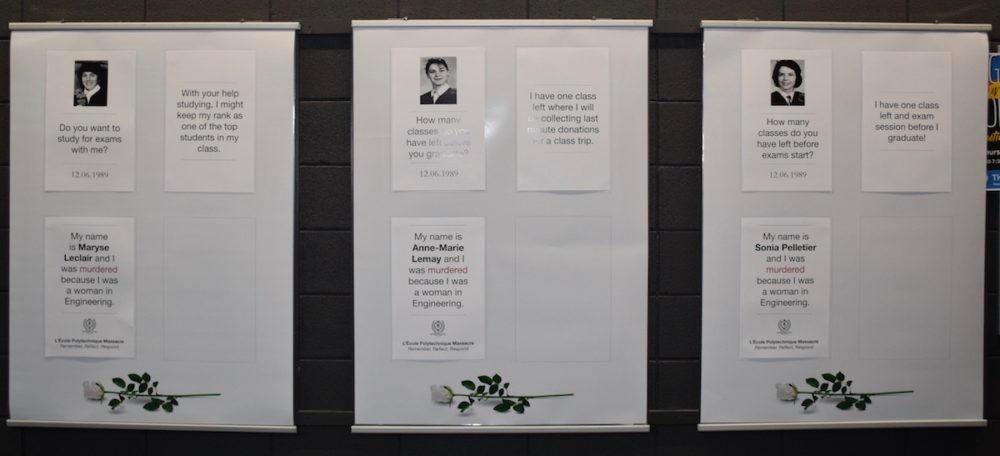

To commemorate those killed in the Montreal massacre – the worst mass killing in Canadian history – black and white images of the women line a hallway in the University of Guelph’s School of Engineering. Each picture is accompanied by a detail about the woman’s life, a simple question of the kind they may have asked as a student and, in most cases, the statement: “I was murdered because I was a woman in Engineering.”

Dec. 6 will be marked in the Adams Atrium of the Thornbrough Building at 2 p.m.

Wells studied engineering at McGill University, on the other side of Mount Royal from École Polytechnique. She completed her degree in metallurgical engineering in 1987 and was working as an engineer at Stelco in Hamilton in ’89.

“I remember moments in time related to December 6, 1989, much more clearly than even my own wedding day,” she said. “It touched me in very, very personal ways.”

The event was especially shocking, she said, because the gunman, a disgruntled 25-year-old describing himself as a hater of feminists, targeted only women. Wells and others prefer that the killer’s name not be used. It is already well-known.

“These were people just like me,” Wells said. “They would be my age now had they lived. The impact of the loss of those women was devastating on the engineering profession. Their creativity, their voices, the diversity of thought – all that they would have brought to the profession. That was a huge loss of talent.”

The annual Dec. 6 National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women is a day to remember the young women who lost their lives, to reflect on the societal conditions that perpetuate violence against and the oppression of women, and to commit to taking action that will improve women’s lives, she said.

“We still have a long way to go in terms of diversifying our profession,” Wells said. “I do thoroughly believe that the more diversity of thought you have, the better the outcome.”

Engineers have a large burden of responsibility in society, and it is vital to have the best minds working on problems to come up with the best solutions, she added.

The number of women entering the engineering profession has increased from about 12,700 in 2006 to just over 26,000 in 2016, according to Engineers Canada statistics. But women make up only about 13 per cent of professional engineers in Canada.

Moussa said U of G’s School of Engineering is dedicated to diversity and inclusion and committed to removing stereotypes that can deter women from entering the field. The school has a strong contingent of female faculty and students, she added.

“If a girl wants to be an engineer, a doctor or a mechanic, she should have the ability to do what it is she wants to do,” she said. “There should never be the idea that girls shouldn’t go into these fields.”

U of G’s biological, biomedical and environmental engineering programs attract large numbers of women, and there are ongoing efforts to bring more women into other programs such as computer and mechanical engineering, Wells said. “I feel we can make a big difference in those programs, which have not been so attractive to women.”

It is important to remember that some people believe women shouldn’t be in science, technology, engineering and math, McInnis said. She said the massacre was a shocking reminder that some see women in those fields as a threat.

And there are those, said Moussa, who harbour extreme misogynistic attitudes. Under certain circumstances, she said, invalid and incorrect feelings of hatred may fester.

“If you allow something to continue to be fed with negative information and feelings, and there is nothing to counterbalance that, like a reality check, then this can happen,” she said, speaking of the 1989 massacre. “This individual happened to hate women. He had convinced himself that his lack of success was a direct result of them being successful. That is dangerous thinking. It is important to understand that many people hate.”

Wells, McInnis and Moussa have worked throughout their professional lives to encourage women to pursue engineering and to improve conditions for women in the profession.

“I made a personal commitment after École Polytechnique that, for every woman murdered, I would work to get another thousand into engineering, so that what the killer wanted to happen didn’t happen,” Wells said. “I devoted the past decade of my life to doing a lot of work in this area.”

The young women who died in Montreal had a clear picture of where they wanted to go in their lives, McInnis said. She called them strong and brave women who were determined to be engineers, a field that they were not necessarily encouraged to go into.

“When I think of them, it is with such sadness,” she said. “There were some really amazing women whose lives were cut short. I would like to think that young women feel that they still have all options open to them and that they don’t have to be fearful. That would be our ideal world.”