By Samantha Beattie, Students Promoting Awareness of Research Knowledge (SPARK)

Icewine — refreshing and sweet tasting — is a luxury drink and a status symbol, particularly among China’s emerging middle and upper classes. And the best icewine in the world, according to Chinese consumers, is meticulously produced by wineries nestled throughout Niagara’s verdant escarpment.

China is the world’s largest and fastest growing importer of Canadian icewine. The country bought more than $7 million worth of icewine in 2011 – twice as much as was purchased in 2008.

But icewine’s increasing popularity has led to the emergence of fake products.

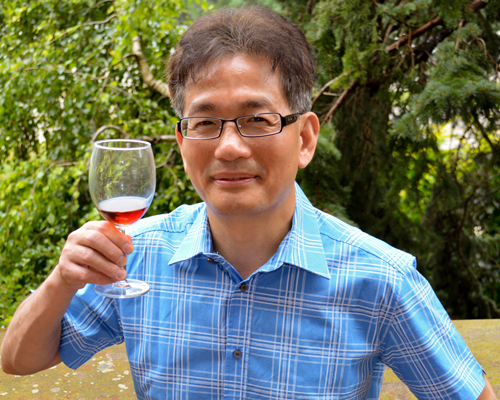

Prof. Lefa Teng, Department of Marketing and Consumer Studies, wants to help put an end to these imitations. He’s teaching Chinese buyers, retailers and consumers how to identify counterfeit companies and products. He’s also collaborating with the wine sector to raise awareness about icewine fraud and how it can be avoided.

“Counterfeit wines are harmful to the industry because they undercut market prices and lower consumers’ standards,” says Teng. “I’m trying to clarify consumer confusion, as well as create a stronger icewine industry that Ontario producers can benefit from.”

Counterfeit wines are made from grapes picked during the regular season in September and October. These wines are then mixed with sugars and some flavours. They still taste sweet, but they don’t meet the stringent standards of real icewine.

Teng urges Ontario wineries to be cautious in using buyers and importers, some of whom will buy real icewine for product tasting but later replace it with counterfeit icewine, claiming it’s Ontario icewine.

A winery’s best defence against fraud is to conduct background checks on importing companies and choose buyers who have complete control over their distribution system.

“For wineries, it’s worth the extra effort in the long run to make sure their reputation is protected as a reliable icewine brand,” says Teng. “There is a taste and quality difference between icewine and counterfeit icewine that many consumers notice.”

Teng found this to be true when he conducted a blind taste test about icewine and late-harvest wine (made with grapes picked earlier in the season around November before they fully freeze) with more than 300 Chinese and Ontario consumers. Although those who were less familiar with icewine couldn’t initially detect a difference, people who were experienced icewine drinkers – having consumed more than five bottles in their lifetime – could tell the two types apart.

Besides taste, there are other indications that a bottle of icewine is counterfeit.

For example, if a 375 mL bottle is priced at less than $60 in China, it is definitely late-harvest wine, Teng says.

The label is also revealing. The product is counterfeit if icewine is spelled as two words; if the Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) regulatory symbol guaranteeing the wine originates in Canada is not on the label; or if there are errors on the back label such as incorrect postal codes.

Last summer, Teng led a conference in Beijing that educated retailers, buyers and consumers about icewine and how to tell it apart from late-harvest imitations.

Teng is also working with Pillitteri Estates Winery and other Ontario wineries to develop champagne-style icewine to match Chinese taste preferences, which he describes as fizzy and sweet.

“China-Canada relations are very good right now, and Ontario icewine already has a strong reputation in China,” says Teng. “I’m helping local wineries benefit from these opportunities by developing the right products and building credible distribution channels.”

Collaborators include Prof. Jie Chen, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, and Prof. Yingyuan Wang, University of Science and Technology Beijing

This research was funded by the OMAFRA – U of G Partnership. Additional funding was provided by Canbest Group and Pillitteri Estates Winery.