What if instead of pulling weeds from your lawn, you picked them and ate them for dinner?

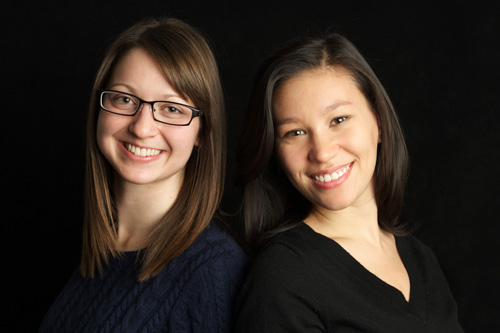

That’s the hope of Michelle (Lamarre) Carkner and Michelle Arseneault, new U of G graduates who have created an edible-weed cookbook with recipes that show you how to turn these unwanted plants into delicacies.

Titled The Good Season, the pair’s cookbook not only includes a variety of tasty weed dishes, but it also provides tips on how to properly identify various edible weeds, how to harvest them, what parts of the plant to eat and how to cook them.

“It’s a way of managing your pests by eating them,” says Arseneault, who along with Carkner completed the bachelor of science in agriculture degree. “The plants are there and they are edible, so why not make use of them?”

Carkner and Arseneault selected five weeds and developed three recipes for each. They chose plants that are abundant in urban areas, such as gardens, lawns and fields, can be easily identified and most importantly, taste good.

The weeds include dandelion, which has a bitter taste; lamb’s-quarters and nettles, which are both similar to spinach; common chickweed, which tastes like peas; purslane, which has a lemon pepper flavour; and common mallow, which has edible flowers that can be used as dessert decorations.

Carkner, who attended culinary school and worked in the industry for three years before starting her degree at U of G, developed all 15 recipes in the book.

“I wanted to create recipes that are familiar to the average person,” she says. “We have to get people to want to go out onto their lawn and pick the weed and try something new. By creating recipes that are familiar, people are more likely to have the confidence to actually try it.”

She began by researching recipes and determining which ones would work best with each weed based on the plant’s flavour. Then she experimented with the ingredients to ensure they complimented the weed. The recipes range from beef burgers to quiche to salsa to dips; there is only one salad recipe in the book.

“We didn’t want to do a lot of salads because we wanted people to think outside of the box.”

Carkner says the most challenging recipe was cream of dandelion soup.

“Dandelion is a bitter-tasting plant, especially if the plant is older, and our culture is not big on bitter taste. I had to play around with adding maple syrup and other ingredients to dull the bitterness.”

Her favourite recipe is the chickweed and ricotta tart with fava beans and mint.

“The chickweed tastes like peas, so having the mint really complements that flavour.”

Although the recipes are all common ones, Carkner says they involve a broad range of cooking difficulty.

“The dandelion soup is very easy because you just put everything in a pot and then blend it, but the tarts are a bit more difficult in that you are working with pastry.”

While Carkner was busy in the kitchen, Arseneault, who has experience in integrated pest management, photographed the weeds for the book and determined their identifying traits.

“Some weeds are poisonous, so it was important to pick weeds that didn’t have poisonous lookalikes,” says Arseneault. “The best way to identify a plant is the shape of its leaves. You are also looking for colour and how they grow, whether the plant is upright or close to the ground.”

Like all foods, weeds have an optimal harvest time, which is late spring to early summer, says Arseneault.

“Early summer is when the plants germinate and begin to grow, so that’s when they are most tender and are eventually a good size for eating. Once the plants produce seed in mid-summer and early fall, they are putting more energy into producing seeds and less into their own leaves and growth.”

These edible weeds can also be incorporated into gardens.

“Instead of pulling the weeds from the garden, people can actually let the edible weeds grow,” says Arseneault. “Not only are they another food source, but these edible weeds will take up space and prevent other weeds from taking over.”

By educating people about edible weeds, Carkner and Arseneault hope to make nutritious food more available and to encourage people to be more open-minded when it comes to what they put on their plate.

“People often think that they have to buy all their food at the grocery store and it has to be perfect looking,” says Carkner. “But if we can get people to eat weeds, then maybe they will look at food differently and be more willing to experiment.”

For more information, visit http://thegoodseason.com/home-2/.

The cookbook project was partially supported by U of G’s Undergraduate Student Experiential Learning Program, which is funded by the knowledge translation and transfer program created by the University’s partnership with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food and the Ministry of Rural Affairs.