It’s a researcher’s dream come true: digitization is making rare books and historical records available and searchable online.

“Computers are changing the way we do pretty much everything,” says Stuart McCook, history professor and associate dean of research and graduate studies in the College of Arts.

Digitization and its impact on humanities research will be the subject of the Tri-University Digital Humanities Workshop from Sept. 30 to Oct. 1. Presented by the University of Guelph, the University of Waterloo and Wilfrid Laurier University, the conference will focus on digital applications and tools for humanities research.

From historians to philosophers, humanities scholars are using computers to do research in ways that weren’t possible before digitization. “It changes the way that we do our work,” says McCook, who uses digital resources for his own research on the history of crop diseases. When he needed to consult an original copy of a book that was only available in the British Library in London, he was able to find a digital copy on Google Books, sparing him the time and expense of travelling to London. He also assigns his students to read PDFs of texts that are hundreds of years old. “In some ways, these databases provide students with truer access to historical documents,” he says.

The vast amount of information available online is also making traditional research skills more important, adds McCook. “Some people will treat everything they see on the Internet equally, whether it’s written by an expert in the field or a nine-year-old in grade school.” That’s why students need to develop analytical skills to filter information and determine its value.

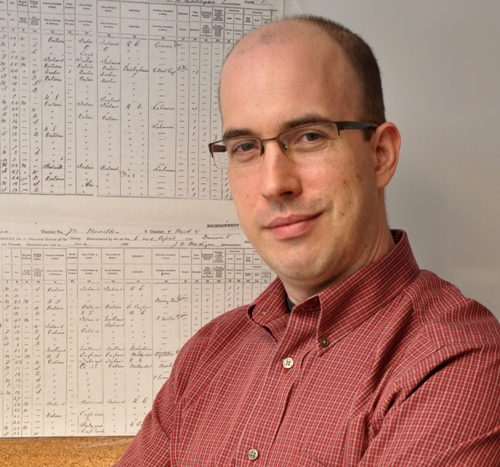

One example of digital humanities research at U of G is People in Motion, a project that tracks the migration of individuals from 1871 to 1911 using census records from Canada, the United States and Scotland. “Canada has a lot people moving in and out, so we don’t actually know if they’re the same people,” says Andrew Ross, a postdoctoral researcher working with Prof. Kris Inwood in the Department of Economics and Finance. “What we’re interested in doing is linking up the exact individuals from each decade.”

Instead of manually searching each census to see how people migrated between the three countries from one decade to the next, the researchers are using an algorithm to search millions of digitized census records to find matches based on the name, sex, age, birthplace and marital status of each individual.

“To do this, we need to teach a computer to automatically link these people because we can’t do it manually,” says Ross. Finding matches between millions of Canadian and American census records wouldn’t be possible without the computing power of Sharcnet, a consortium of Canadian academic institutions that share a network of high-performance computers. “We’re creating the infrastructure so people can do this research,” he adds. “We’re setting up a database of links for other scholars to use.”

Previously, using paper records to track the movements of people across time and geographic areas was tedious, if not impossible. Because of the scale, it just wasn’t possible to do the research manually, says Ross. The population of a township, for example, could drop from 100 per cent in 1871 to 70 per cent a decade later. Where did 30 per cent of the population go? Now, researchers can enter the names of people in the missing population and match them with names stored in a nationwide database to find out where they moved within Canada.

For more information about the Tri-University Digital Humanities Workshop, visit www.uoguelph.ca/arts/dhw2011.