New U of G research investigates how dance and other creative arts could fill major gaps in Canada’s health care

Science hasn’t fully explored it. But dancing may have the power to slow down the fastest-growing neurodegenerative disease in the world.

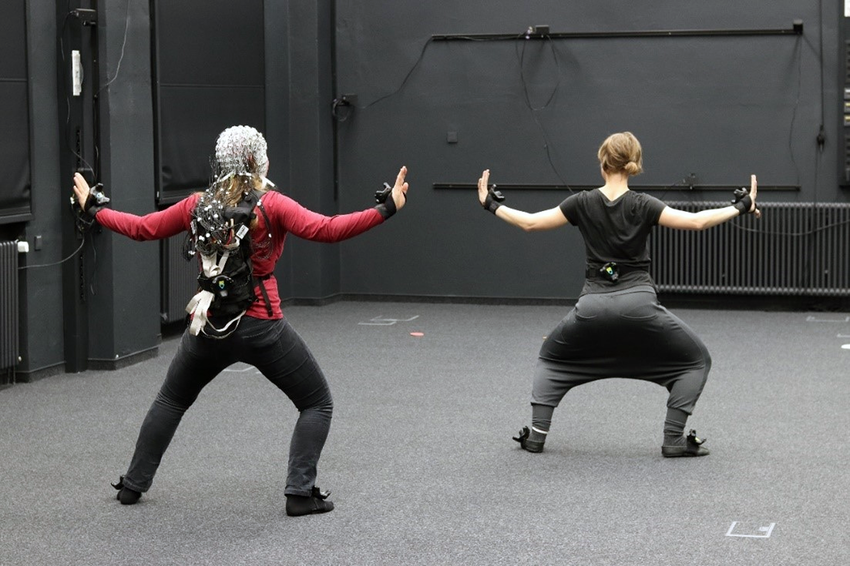

“It seems simple, but it’s actually very rich to move with someone else,” says Dr. Rebecca Barnstaple, a University of Guelph professor in the College of Arts.

With a PhD in dance studies and neuroscience, trained in dance/movement therapy, Barnstaple has been involved in dance programs and research with clinical populations for over a decade, witnessing profound moments of connection along with changes in movement quality.

Dancing activates attention, memory and coordination, Barnstaple says, stimulating new neural connections and potential benefits that linger far beyond a single session.

Many of their participants walk away feeling lighter, freer.

“I think the easiest thing that you can see is that dancing makes people happy. Having a neurodegenerative condition like Parkinson’s can be very isolating, but connecting with others through movement has this positive, holistic effect on the body.”

Now, Barnstaple is taking these insights further, leading a new research project that investigates connections between participation in creative arts activities — such as dance, mime or singing — and Parkinson’s disease (PD).

PD currently affects more than 110,000 people in Canada, a figure expected to grow to 150,000 Canadians by 2034. Yet access to diagnosis and treatment remains slow. The average wait time for a PD diagnosis in Canada is 11 months and, in some regions, over two years.

“During that time, people are not receiving treatment, or maybe not the correct treatment, and they’re left with a lot of questions and anxiety. Could arts-based resources address this gap in the health care system? I think so.”

Social prescribing connects Parkinson’s patients to resources

Entitled “If Art Were a Drug,” Barnstaple’s project will develop the first national arts resource hub for people with Parkinson’s, connecting them to community resources and facilitating “arts prescribing” for health care professionals.

Encouraging people with Parkinson’s to retain or increase their level of activity is well-known to slow disease progression. So while the arts may not replace drug treatments, Barnstaple says, they may offer meaningful support when receiving a new diagnosis.

“Could these programs help people make it through until they see their neurologist?” Barnstaple asks. “Could they be in better shape than if they did nothing?”

To investigate, the project will employ social prescribing, in which medical professionals connect people to non-medical services, such as art programs, to reduce isolation, foster social connections and increase quality of life.

It is a health care framework growing in popularity. A recent report found that every dollar spent on social prescribing saves the health care system $4.

“It’s a shift from ‘what’s the matter with you’ to ‘what matters to you?’”

Social prescribing typically involves a link worker, someone who helps patients navigate community resources. Physicians often lack the time or knowledge to make these community connections themselves, so link workers fill that crucial gap.

The new project will create a virtual link worker, an online equivalent that can refer people with Parkinson’s to specific arts-based programs and help health care professionals explore “prescribing” arts-based supports for people with Parkinson’s.

In collaboration with Canadian Open Parkinson’s Network (C-OPN), this project will also give researchers the ability to access clinical outcomes for consenting participants. This addresses a current gap in medical knowledge about the impacts of dance and other creative activities on standardized health outcomes.

This first-of-its-kind model could also be applied to other diseases, Barnstaple says, who calls for the arts to be more integrated into Canadian health care.

Unique science research brings out the artist within

Over multiple years, the project will bring together people with PD and researchers across disciplines – biomechanics, neuroscience, sociology, creative arts and more. The team aims to track mobility, emotional well-being and social connection, as well as other metrics science has traditionally overlooked.

“How are we going to measure the whole picture?” Barnstaple says, explaining the difficulty in quantifying the effects of creative experiences. “And do we even need to? If people are smiling, feeling better, and there are no adverse effects, why shouldn’t we be recommending this?”

The research process is also unique for pairing clinical data with lived experiences.

“We’re inviting people into a creative process,” Barnstaple says, “empowering people with Parkinson’s to find the artist within themselves.”

Interdisciplinary team aims to track mobility, emotional well-being and social connection

Interdisciplinary research inspires new U of G program

Barnstaple’s research is further inspiring students in a new U of G program, the Bachelor of Creative Arts, Health and Wellness (BCAHW). The first program of its kind in Canada, the BCAHW bridges students’ passion for music, studio art, creative writing and theatre with health care.

“I talk about this in first-year classes: When you work with people experiencing health challenges, you cannot come in with a rigid protocol you’re going to implement no matter what,” Barnstaple says. “You have to be equipped with creativity: ideas, tools and techniques that will allow you to respond to people in the moment.”

This insight emerged from Barnstaple’s postdoctoral work at U of G’s International Institute for Critical Studies in Improvisation, now passed on to the next generation:

“You have to be willing to improvise and co-create. There is an art to health practice.”

This project is supported by the Government of Canada’s New Frontiers in Research Fund Exploration stream in collaboration with Drs. Kimberly Francis and Lori Ann Vallis who serve as research associates.

“I have seen first-hand the life-changing effects of this research,” says Francis, director of the School of Fine Art and Music. “This award reinforces Dr. Barnstaple’s place as a global thought leader in arts and health and will result in a transformative, highly sought-after resource for people living with Parkinson’s disease.”

“Dr. Barnstaple brings an incredible wealth of experience and expertise in addition to creative energy to this project,” says Vallis, professor in the College of Biological Science. “I am so excited to see where this research takes us in the coming months and years ahead and hope that our work improves quality of life and long-term patient care in those living with PD.”