By Karen Mantel

When it comes to managing the impacts of antimicrobial use in animals and the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance, Canada could learn a thing or two from its Olympic athletes, says Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) professor John Prescott, Department of Pathobiology. He sees parallels between the issues surrounding antimicrobial resistance and the take-home message from cross-country skiing gold medalist Beckie Scott, who spoke at a conference he helped organize in 2011.

Scott said reaching your goals takes time and continuous improvement and refinement of seemingly small details to perfect techniques.

Prescott says continuous improvement is also key in the ongoing issue of antibiotic resistance. He’ll outline how Canada is faring in this area during a presentation today at the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association’s annual meeting in St. John’s, Nfld. The program includes a full day of talks devoted to the theme “Antimicrobial Stewardship: A New World Order.”

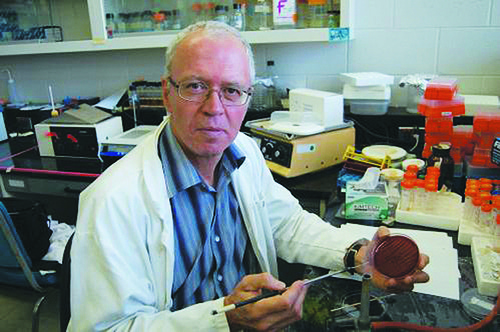

“We need to identify the problems, address the issues and move on so that Canada can achieve gold in this area,” says Prescott, who retired this spring after a 39-year career as a bacteriologist at OVC.

He says there are many areas where continuous improvements need to be made, including “how we use antibiotics, how we dose them, the diagnostic side of things, how we regulate them, who uses them, creating new antibiotics. There are dozens of things we can do to stabilize the resistance problem.”

The concept of stewardship is an important one, adds Prescott. “It’s the idea of taking responsibility for long-term management and care of something of enormous value.”

Prescott and other OVC scientists, including Profs. Scott McEwen in the Department of Population Medicine and Patrick Boerlin and Scott Weese in pathobiology, have helped make OVC a leader in the field. For many years, they have been involved in research on antibiotics, the epidemiology and movement of resistant bacteria, and how antibiotics are used by veterinarians, as well as the development of guidelines for practitioners and input into public policy.

McEwen chaired a 2002 national investigation into the impacts of antimicrobial use in animals and its relationship to antimicrobial resistance. The resulting report provided 38 recommendations to Health Canada to better protect the health and interests of Canadians in relation to antibiotic use in food animals.

One of those recommendations supported the development of a Canadian antimicrobial surveillance system. The Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS) is co-ordinated by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), with the animal component located in the Laboratory for Foodborne Zoonoses in Guelph. It looks at both antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial use.

Part of the CIPARS surveillance program involves collecting retail and abattoir meat samples and comparing resistance in selected intestinal bacteria to resistance in selected intestinal bacterial pathogens in Canadians.

There is a great synergy between CIPARS and the University of Guelph, says Prescott, and the CIPARS program has funded numerous graduate students at OVC. “I think it’s been a great example of a federal government agency synergizing with a university on an important problem. I’m quite in awe of what CIPARS has achieved.”

Prescott has co-chaired three national conferences on antimicrobial drug use in animals in Canada, all involving OVC faculty as well as collaborators from PHAC; industry; national farm organizations; the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs; and consumers. A subsequent committee dealing with antimicrobial stewardship in agriculture and veterinary medicine has continued to teleconference bi-monthly since 2011 to keep a national dialogue going.

Recently the group prioritized what needs to be done in this area, identifying 17 recommendations and ranking Canada’s work in this area against the World Health Organization, World Organization for Animal Health, Health Canada’s 2002 report and proposed changes in food animal antibiotic use from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The top nine recommendations relate to regulation, says Prescott.

“Overall, the group gave Canada a C minus as a ranking because we fall below international standards and the recommendations in the 2002 report to Health Canada. This means we think that, overall, we have somewhere between an adequate and barely satisfactory understanding of the issues, and require somewhere between improvement and marked improvement to meet modern standards.”

While the European Union made changes to stop the development and movement of antibiotic resistance a long time ago, change has been slower here, says Prescott. However, he says Health Canada recently announced it will be developing options to strengthen veterinary oversight of antibiotic use in animals and removing the use of antibiotics as growth promoters, similar to measures that are being implemented in the United States.

Prescott adds that resistant bacteria and resistance genes can move around easily, and improved stewardship of antibiotics in companion animals is equally if not more important as improved stewardship in food animals.

Changes need to happen at regulatory levels in Canada, he says, “but we need to have an integrated view of things.” Stewardship is about far more than regulations: it has multiple dimensions. Stewardship is about a culture of continuous improvement in every aspect of the use of antibiotics, an effort as hard and focused as that involved in winning gold in the Olympics. Ultimately, Prescott says, Canada needs to be on the podium.