Looking for a down-to-earth scientific project for his students, Prof. Joe Ackerman went all the way to VENUS. That’s the Victoria Experimental Network Under the Sea, an ocean observatory for studying everything from tides to temperatures to marine life near Victoria, B.C.

Guelph students taking “Introduction to Aquatic Environments” with the Guelph integrative biology professor use real-time, online data from VENUS to learn about scientific inquiry.

Taken by students in several majors offered by the Department of Integrative Biology, including marine and freshwater biology, this third-year course has no lab or tutorial. Looking for a data source to help those roughly 100 undergrads hone smarts in developing and testing hypotheses, Ackerman hit upon the novel ocean-monitoring project on Canada’s west coast.

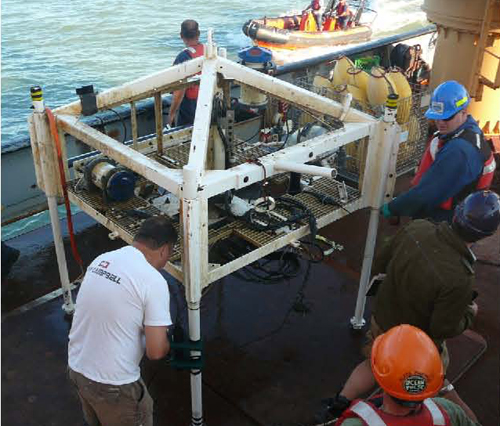

VENUS operates scientific instruments installed in Saanich Inlet, the Fraser River delta and the Strait of Georgia. Sensors track various environmental factors including seawater temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, ambient sounds (including whale “songs”), currents and tides.

Information collected by those devices has helped researchers looking at climate change effects, fishing impacts and even decomposition rates of bodies in water.

Among those scientists is Ackerman, who belonged to a VENUS research team studying factors such as dissolved oxygen about 100 metres down on the sea floor. He has also studied boundary layer dynamics at the bottom of lakes, rivers and the coastal ocean.

“People are looking at real-time data, not taking snapshots on board research vessels,” he says of the ocean project run by researchers at the University of Victoria (UVic). “It’s an innovative way of doing oceanography.”

Sent by fibre-optic cables to UVic, information is available on the Internet to ocean researchers and the general public at http://venus.uvic.ca/.

Ackerman’s students use the data to develop and test hypotheses relating dissolved oxygen with other factors such as water temperature, currents and conductivity. He says the assignment helps develop vocabulary – such as t-tests and linear regression – and skills in the scientific method among budding scientists.

Giulia Rossi, a third-year major in marine and freshwater biology, says VENUS data helped in understanding relationships between water temperature, salinity and other variables. “Without VENUS, there was no real way to get such accurate real-time data that would allow us to visualize relationships so clearly.”

Ackerman’s students have also used data from a surface buoy maintained by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Environment Canada.

In 2007, the University of Victoria established Ocean Networks Canada (ONC), which runs VENUS and another undersea observatory west of Vancouver Island called NEPTUNE Canada. Data from both projects have been used in school lessons and assignments across Canada and abroad, says Ellyn Davidson, post-secondary education co-ordinator for the ONC Centre for Enterprise and Engagement.