We assume science is objective, uniquely isolated from politics. But as University of Guelph geography professor Dr. Jennifer Silver writes: “Science is not separate from or neutral to power.”

The questions researchers can ask, the funding that is granted and the methods that inform these decisions are all shaped by norms and values that often align with socio-economic interests.

But values and societies change over time, and the social sciences and humanities have a lot to tell us about the relationships between science and inequity.

Many disciplines show us that the goal of controlling people and settling territories – often discussed as “colonialism” — helped form many institutions with decision-making power today.

Silver brings this critique to her work in the College of Social and Applied Human Sciences, where she studies fisheries management and coastal communities, the history of fisheries science and the ways that management decisions can marginalize Indigenous and other coastal communities.

Recently, she was invited to discuss her work with a committee formed by The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to address the lack of diversity in ocean science and research and to offer tangible ways forward:

“Environmental decision-making, including fisheries management, privileges Western science as a knowledge system, which can exclude local observation, community goals and other ways of knowing.”

Science and institutions must account for their history

As a social scientist, Silver is frequently invited to work on the western coast of Vancouver Island, an important part of which is listening to concerns and experiences in communities. She’s seen how top-down choices ripple across peoples’ family histories and legacies, their profound sense of community, purpose and place.

Speaking before the committee to “increase diversity in oceans research,” she was pleased that she could move their conversation past commonly stated solutions like, Make sure there is good workplace training. Invest in more mentors.

“Making the workplace comfortable and accessible, all of that is important,” Silver says. “But my main point was that institutions of environmental science that hold decision-making power need to be recognizing and accounting for their histories.”

Silver and a diverse team of authors came together to outline one such history in a 2022 essay “Fish, People and Systems of Power” published in the journal The American Naturalist. Among other themes, they describe how the end of the Second World War saw a surge in fisheries commercialization and the criminalization of Indigenous fishing practices.

Examining Pacific herring specifically, the team traced how subsidized industrial fisheries catalyzed the collapse of herring stocks. Indigenous peoples, who had sustainably managed these stocks for generations, were marginalized, their traditional practices outlawed and their knowledge dismissed.

Today, this has led to a complex market-based licensing system. As Silver has written in The Conversation Canada, governments on the West Coast grant fish licences and limit the right to harvest in certain places. In practice, licences can accumulate in the hands of wealthy investors and powerful firms, who can in turn sell and lease them to earn revenue and build control.

As waters are subject to licensing, they’re also statistically parsed by Western science, and the models treat fish as biomass to be fine-tuned and optimized.

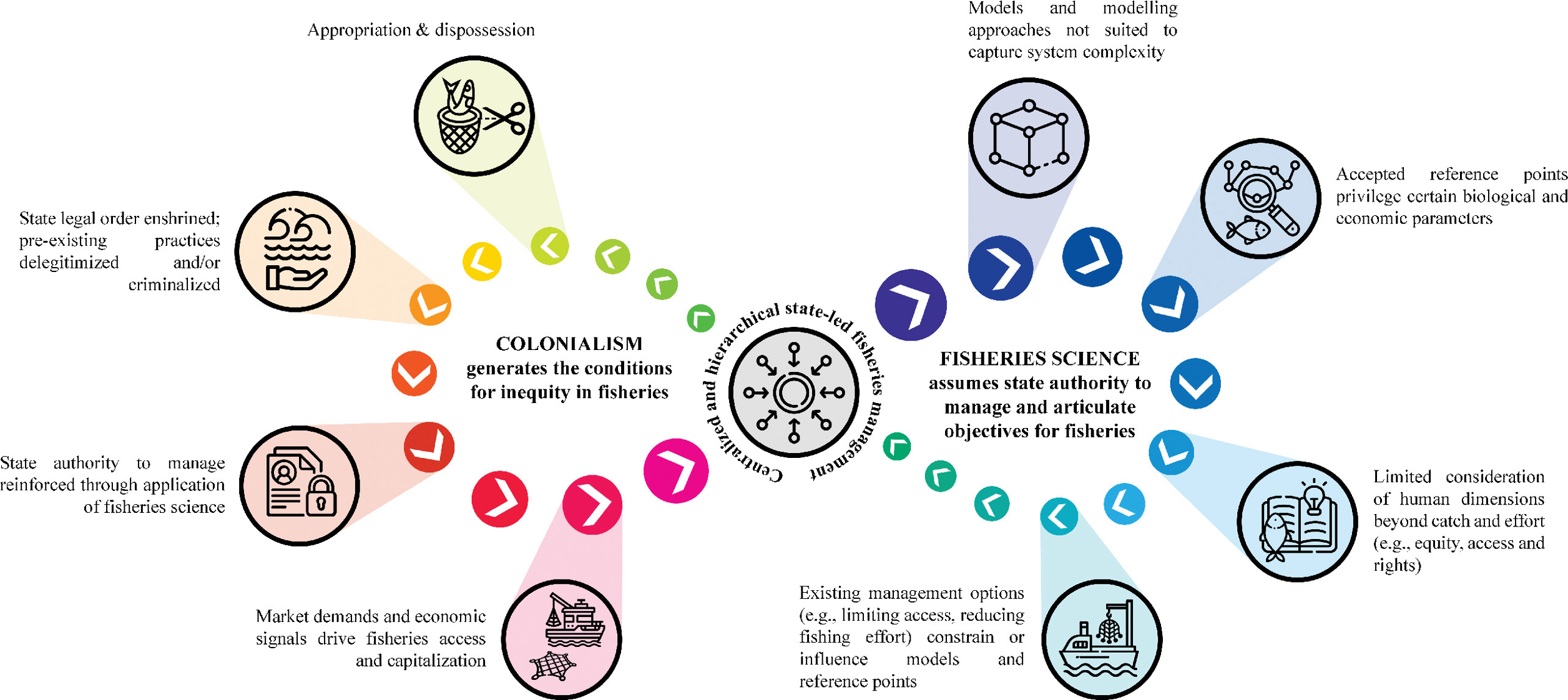

Linking this back to the history helps us appreciate the “intertwining” of science, institutions and colonialism that Silver and others emphasize.

“A place in the ocean adjacent to someone’s community becomes a single data point, used to make a scaled-up or generalizable conclusion,” Silver says. “I constantly hear that the way decisions are made doesn’t feel like it’s connected to what people experience in their everyday lives.”

In other words, the large scale of Western science can, ironically, yield a sense of tunnel vision.

“When you’re only making decisions about one type of fish, you miss the broader web of ecological and social connections,” Silver says. “A person living there can see the implications of the smallest changes for the other species around.”

Feedback between colonialism and fisheries science (source: The American Naturalist).

The more people of different backgrounds, the more creative the solutions

For Silver, the more people of different backgrounds who can be in positions of leadership, the better institutions can come up with creative solutions. Otherwise, she says, it’s not likely anything will be done differently.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will create a report based on Silver and others’ recommendations that outlines actionable strategies. Silver hopes the agencies that have convened — powerful U.S. organizations that can effect change if they account for their histories – will take these lessons forward.

Silver has also recently won a Partnership Development grant with the University of Waterloo, Ecotrust Canada and T. Buck Suzuki Foundation to address Canadian commercial fisheries and their impact on fishing people and West Coast communities.

Contact:

Dr. Jennifer Silver

j.silver@uoguelph.ca