Custom-made field kits will allow University of Guelph students learning from home during the COVID-19 pandemic to conduct stream sampling this fall.

Custom-made field kits will allow University of Guelph students learning from home during the COVID-19 pandemic to conduct stream sampling this fall.

The novel kits being assembled this month will enable students in a fourth-year freshwater course to learn about water chemistry and effects of pollutants on aquatic health in local streams close to home.

And for the first time this fall, the materials will also enable students in “Limnology of Natural and Polluted Waters” to share their findings with an international citizen science project intended to assess and improve the health of streams and rivers more broadly.

Course planners in the Department of Integrative Biology hit upon the DIY kits as an alternative to Guelph-based, hands-on instruction during the pandemic. The kits will be provided along with virtual instruction including videos for up to 75 students in the course, said Sheri Hincks, lab coordinator.

“Usually we take students to streams and lakes, and they sample the water using different equipment. We’re changing our sampling protocols,” said Hincks.

Fieldwork normally involves wading knee-deep in Guelph’s Speed and Eramosa rivers to take physical and biological samples. Sampling typically happens upstream and downstream from municipal water treatment plants or corporate plants.

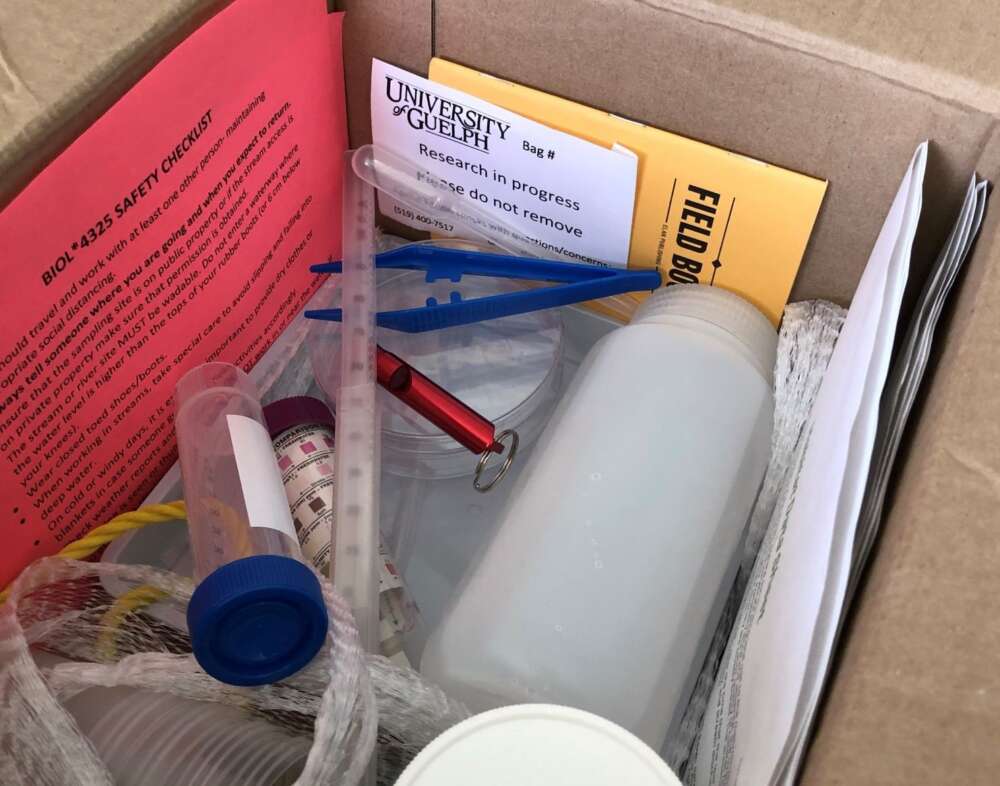

Early this fall, U of G will mail kits to students including everything from bags and sorting trays for collecting insects to live Daphnia (water fleas) used in freshwater toxicity testing.

This year, the class will also take part in the Leaf Pack Network (LPN), a project run by the Stroud Water Research Center based in Avondale, Pennsylvania, that enlists citizens and school groups to assess stream health. Established in 1967, the U.S. centre is intended to improve knowledge and stewardship of freshwater systems through research, education and watershed restoration.

The field kits will include packs to be filled with leaves from stream banks. Placed in the water for several weeks, the collected leaves decompose and attract aquatic insects such as mayflies and caddisflies.

Students will retrieve the packs to sort, identify and count the bugs, using a virtual insect ID resource. Standard calculations allow students to compute a diversity index that indicates whether the stream is relatively clean or polluted. (Types and numbers of aquatic invertebrates can indicate stream health.)

The students will use an interactive, online map developed by U of G’s OpenEd to share their results with classmates from home.

Data will also be shared with the Leaf Pack Network for its wider stream health monitoring project. “Students are contributing to a bigger database, and researchers have access to the information they collect,” said Hincks.

Begun almost 20 years ago, the LPN project involves institutions throughout the United States and in 12 countries worldwide. Tara Muenz, assistant director of education and LPN administrator, said, “As far as I know, we have not had a university in Canada in the Leaf Pack Network to this level before.”

She said the project gives individuals and groups a way to raise awareness of stream health and promote waterway stewardship globally.

“The Leaf Pack Network offers individuals a real-world experience in stream health assessment, empowering them to use the data they collect to protect these freshwater systems and to be more eyes and ears out there watching for potential pollution events.”

U of G students lacking safe and ready stream access will be able to work with information about samples collected by instructors in Guelph.

Using the new kits, Hincks said, “Students still get to experience fieldwork. This is real-life stuff that aquatic biologists would be doing. They can get into a local stream in their watershed and decide whether it’s being impacted and what’s causing it.”

In a separate DIY project, some 150 students in this fall’s introductory biology course offered by the departments of Integrative Biology and Molecular and Cellular Biology will receive seeds and materials to grow corn and beans at home. Students will work in virtual groups to study how fertilizer affects plant growth rates.

This curriculum lab unit normally occurs through the fall in the Science Complex greenhouse, said integrative biology Prof. Pat Wright, course coordinator. Wright said the course is intended for non-science majors.

“We’re trying to get students to understand how scientists collect data and actually provide evidence for or against a hypothesis,” she said. “This experiment allows students to understand challenges that come with collecting this primary data.”

To learn more about what the U of G student experience will look like this fall, visit the Virtual Campus page.

Contact:

Sheri Hincks

shincks@uoguelph.ca