Cities are likely to get hotter under global warming. But by countering the intense radiant heat given off by sidewalks, buildings and other infrastructure, urban landscaping and construction can make pedestrian spaces feel 10 degrees Celsius cooler or more, says a University of Guelph atmospheric scientist and co-author of a pioneering study.

Published recently in Science of the Total Environment, the study provides the first urban micrometeorological measurements of pedestrian “thermal exposure” during extreme heat in a dry climate, said Prof. Scott Krayenhoff, School of Environmental Sciences.

How extreme?

For their one-day study, Krayenhoff and Ariane Middel, a professor at Arizona State University (ASU), picked a record-breaking heat day: June 19, 2016, in Tempe, Arizona, when the thermometer reached a high of 48 C. The highest temperature recorded in Canada was 45 C on July 5, 1937, in southern Saskatchewan.

“We had a gruelling day,” said Krayenhoff, who helped conduct the study and analyze the data as a post-doc at ASU in 2016-17. “To stay hydrated, we drank all the available sports drinks from a nearby vending machine.”

Between 10 a.m. and 9 p.m. that day, the duo measured mean radiant temperature (MRT) at 22 locations on the ASU campus. MRT consists of shortwave radiation such as sunlight and longwave radiation emitted by hot surfaces such as concrete or asphalt.

Because MRT combines all the radiation hitting a pedestrian from all angles, it helps provide a better measure of the human thermal experience than measuring air temperature alone, said Krayenhoff.

“What matters for your thermal experience is much more than the air temperature,” he said.

While air temperature may stay relatively constant across a city, how hot you feel may vary by up to 15 C depending on whether you are standing on an asphalt parking lot or under a tree, he added.

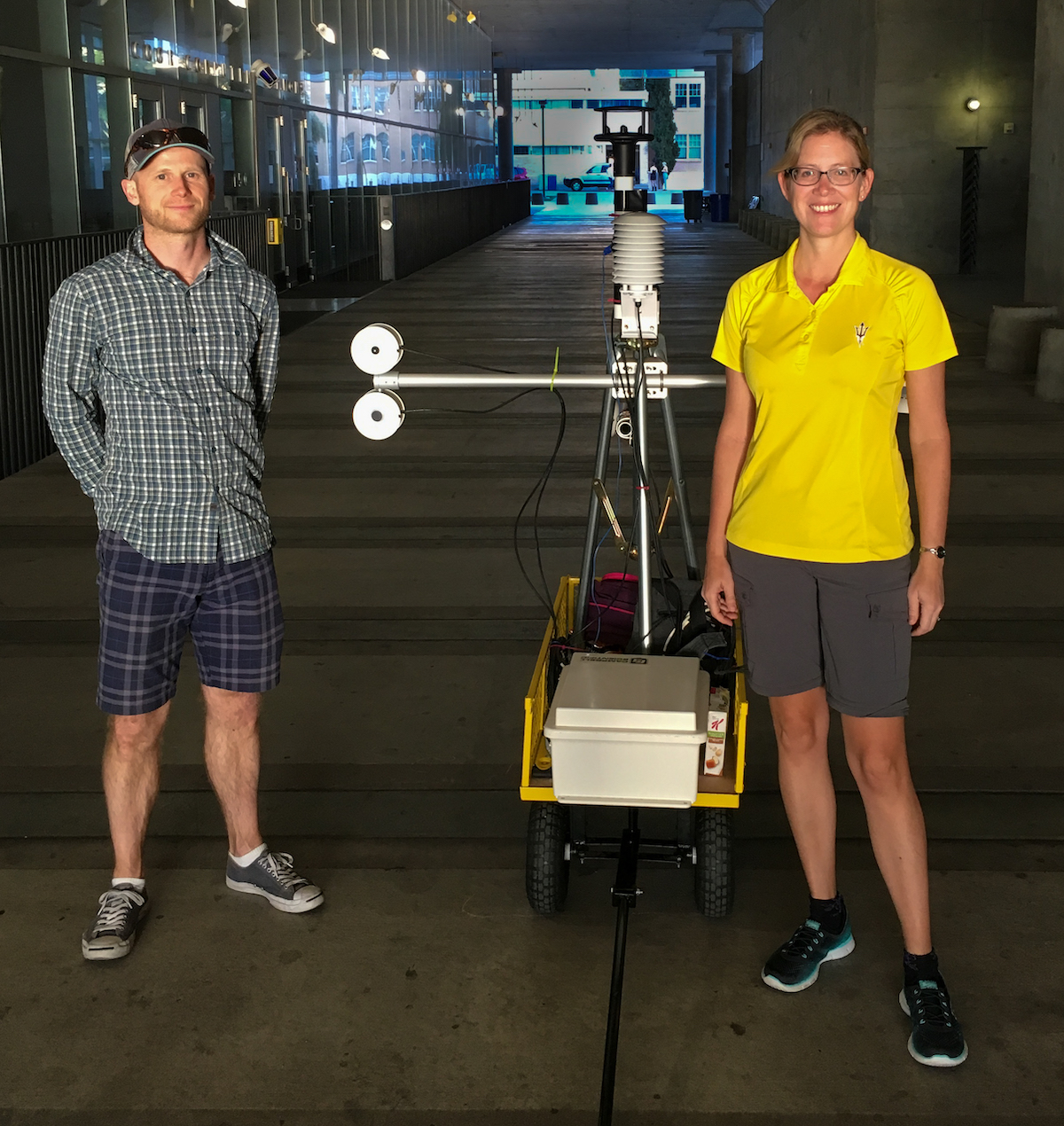

The researchers used Middel’s specially designed mobile cart – dubbed MaRTy – equipped with radiometers as well as instruments for measuring air temperature, humidity, and wind speed and direction. They also photographed the surroundings to match up radiant heat with its sources. They tested sun-exposed and shaded areas as well as ground covers – grass, concrete, asphalt – and an area under solar panels.

Besides verifying the importance of MRT, they found shade was the best way to cool pedestrians, followed by cooling ground surfaces such as grass. The hottest location was a sun-exposed “concrete jungle,” while other hot locations were next to walls reflecting radiation.

“Shade is key to reduce pedestrian thermal exposure during the hot summer months in Phoenix, but ground surfaces and vertical surfaces matter, too,” said Middel. “Sun-exposed walls and impervious surfaces such as roads and parking lots negatively impact pedestrian comfort because they emit heat.”

Tree-shaded lawns were among the most comfortable outdoor spaces, but they require irrigation. Krayenhoff was surprised to find that trees impede nighttime cooling by effectively trapping longwave radiation being emitted from the ground overnight. However, he said that slight warming effect was far outweighed by the daytime benefits afforded by trees, including shading and carbon capture.

The results from this study may help with determining optimum planting for city streets, including where to locate trees, how big and how far apart, said Krayenhoff. This information may also underline for urban planners the need to consider adaptive designs for hotter cities, he added.

Their findings might also be included in green building codes and urban forestry plans, said Middel.

During a planned repeat study in Guelph, Krayenhoff hopes to test the effects of higher humidity in southern Ontario. He is also combining MaRTy’s measurements with a mathematical model that allows researchers to test the effects of street designs on pedestrians’ heat exposure.

“Thermal comfort of pedestrians does not always appear to be the first priority for planners, understandably,” said Krayenhoff. “However, if we want urban space to remain livable during summertime as things get hotter, this work is going to have more impact. We want to engage with planners and designers.”

Contact:

Prof. Scott Krayenhoff

skrayenh@uoguelph.ca