If you accurately follow the food safety instructions in some of the new popular Canadian cookbooks, you could make yourself sick, according to a new University of Guelph study.

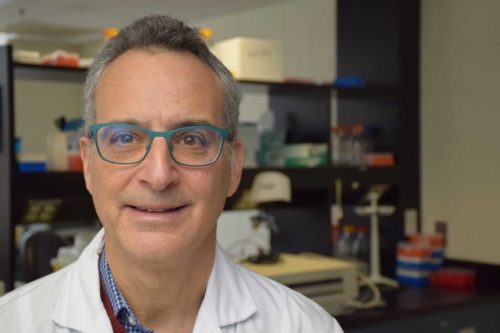

Prof. Jeffrey Farber and his students analyzed the food safety instructions in 770 recipes involving meat or seafood from 19 popular Canadian cookbooks and found they were missing important information or providing inaccurate information.

In fact, 96 per cent of the cookbooks studied provided incorrect temperatures or failed to include a minimum internal temperature to determine if food was safely cooked.

This study was featured in the Toronto Star , the National Post as well as CBC News Online.

“The household kitchen is often the last line of defence in the prevention of food-borne illnesses, of which there are about four million cases annually in Canada,” said Farber, director of U of G’s Canadian Research Institute for Food Safety. “For that reason, it is vital that the cookbooks Canadians use at home make every effort to protect users from illness.”

According to estimates, around 50 per cent of food-borne illness can result from unsafe food handling in the home, he added.

“A kitchen in the home can harbour and spread food-borne pathogens just as much or more than one outside the home.”

Published in Food Control, the study included cookbooks selected from a list of 30 published between 2015 and 2017 and deemed to be the best in the country.

To be considered unsafe, the recipes analyzed had to be lacking in accurate information needed to prevent illness derived from food-borne pathogens.

The researchers found less than 0.3 per cent of the recipes reviewed advised readers to wash their hands prior to starting meal preparation and after touching raw materials.

Only 2.7 per cent of recipes advised readers to begin work on a clean surface or work area and/or use clean utensils.

Seven food categories were defined in the study including seafood, eggs, fresh pork, poultry, fresh meat, ground meat and meat mixes. Recipes in all categories were scrutinized for safe or unsafe food preparations instructions related to thawing and washing, internal cooking temperature, food-handling practices, steps taken to prevent cross-contamination and post-cooking instructions such as serving and storage.

When it came to unsafe thawing and washing, recipes involving the preparation of pork had the highest prevalence of unsafe instructions at 24.6 per cent. Seafood recipes were unsafe 12.3 per cent of the time, and recipes with ground meat were unsafe 8.7 per cent of the time.

Researchers also found recipes in cookbooks often include subjective indicators, rather than scientific ones, to describe the degree of doneness, especially as it relates to the time frame, colour and texture of the dish, added Farber.

“When the cookbooks are providing misleading or inaccurate information, or don’t promote basic practices like thermometer use, that is an issue,” said Farber, who worked with post-doctoral student Kavita Walia and graduate student Maleeka Singh on the study. “For example, sometimes the recipe did provide a minimum internal temperature, but gave the incorrect temperature.”

Food-borne illness is a serious health concern in Canada, he added. The authors of cookbooks may leave out appropriate safety guidance because they are unaware of the full extent of the problem, he said.

“But they could be helping to prevent food-borne illness. They could include information for preventing cross-contamination, guidance on how long to keep meat and seafood out at room temperature and encourage the use of thermometers to measure the endpoint temperature of food, instead of subjective indicators. They have a role to play in providing food safety information and in not providing misleading or inaccurate information, which could lead to full-blown illness.”

Contact:

Prof. Jeffrey Farber

jfarber@uoguelph.ca