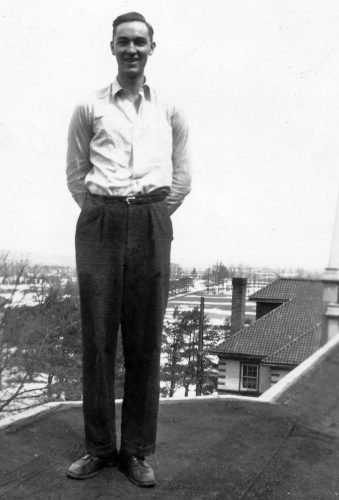

Now “almost 99” years of age, Henry “Hank” Orr, a retired University of Guelph professor, was an Ontario Agricultural College (OAC) student during one of the most tumultuous times on the Guelph campus and in the world.

“I started at OAC in ’39, the year the war broke out,” says Orr, a ’43 OAC alumnus who, as far as he knows, is the last surviving member of his graduating class.

“We didn’t know what to expect or what would happen.”

As the world became embroiled in a war that spread rapidly around the globe, post-secondary life in Guelph carried on normally, he says. There were nourishing meals served in Creelman Hall and all the milk you could drink. There were plenty of activities on campus to get involved in, and Orr led an active student life both on and off campus grounds.

But as his second year at OAC ended, the campus – consisting of the agricultural college, the Macdonald Institute and the Ontario Veterinary College – was repurposed for war.

“We had two years in residence and then the Royal Canadian Air Force moved in and we had to move out and find an apartment off campus for the last two years,” says Orr.

The air force requisitioned a large portion of the campus, turning it into the RCAF Station Guelph, part of the Second World War British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Among the station’s schools were one to train airmen and airwomen as chefs and a larger one to train wireless operators.

It was a temporary wartime measure, but a historic one. Orr recalls how the campus was dramatically transformed from a pastoral college environment to one teeming with military trainees.

The central hub of the campus was fenced off and tight security was imposed. The grounds and buildings became crowded, but classes continued.

Orr was required to take military training in his final two years of study. “We were in uniform about three or four days a week.”

Throughout his time at OAC, Orr was affected by the war deeply and personally.

“Every year we lost fellas who had joined up in the war,” he says, reflecting on his memories of that troubling time while sitting in a comfy chair in his small apartment in a Guelph retirement residence.

“I lost some good pals who were killed before it was over.”

There was a tradition each fall during the war years, Orr recounts, of students volunteering to go west to help with the harvest. The need for farm labour on the prairies was great during the war, with so many young men off fighting and so many having died.

“A few days after we returned for the fall semester in ’42, 49 of us Aggies went west for two weeks,” he says. “We took the train across the country. When the trains stopped, if we saw a store nearby we would all rush over to get a few things for the trip. It was a lot of fun.”

The work on the prairie farms was hard and the hours long.

“You got up bright and early in the morning, had a breakfast and then you had to go out and harness your team, hook it up to the wagon and out you went into the fields with your fork,” he says. “You forked the sheaves of wheat onto the wagon and when you had a load you went to the threshing machine and forked them into the thresher.”

Orr studied crop science at OAC but was encouraged by a beloved professor to take a one-year poultry specialist program after he graduated and completed his military service. At that time, the science of poultry nutrition, health and management was in the early stages of development.

Orr grew up around chickens on the family farm in southwestern Ontario. Feeding his mother’s flock of hundreds of hens was one of his many boyhood chores.

“My mother always had laying hens,” says Orr. “I think she got up to three or four hundred or more.”

The hens and their eggs, he says, helped put him through university.

With that special connection, it was not a great leap for him to study poultry.

After graduating from OAC, and serving in the military in Saint John, New Brunswick, and Goose Bay, Labrador, Orr returned to OAC to complete the poultry program, then earned a master’s degree in poultry products in Pennsylvania. He would return to Guelph as an OAC professor.

For the next roughly 45 years, he investigated poultry processing and studied ways to improve the yield of poultry meat and methods of ensuring egg quality.

The humble chicken and egg have long been dietary staples, but nothing like the industry of today, says Orr. “The changes in technology today sort of boggle my mind. Things we did by hand in the past are now all done by machine.”

While he is happy to have contributed to and witnessed the changing industry, Orr says, the years he spent teaching were his most rewarding.

“I really enjoyed the students,” he says, adding that seeing them mature, listening to them and helping them along in their development, and then watching them graduate, were the most rewarding aspects of his professional life.