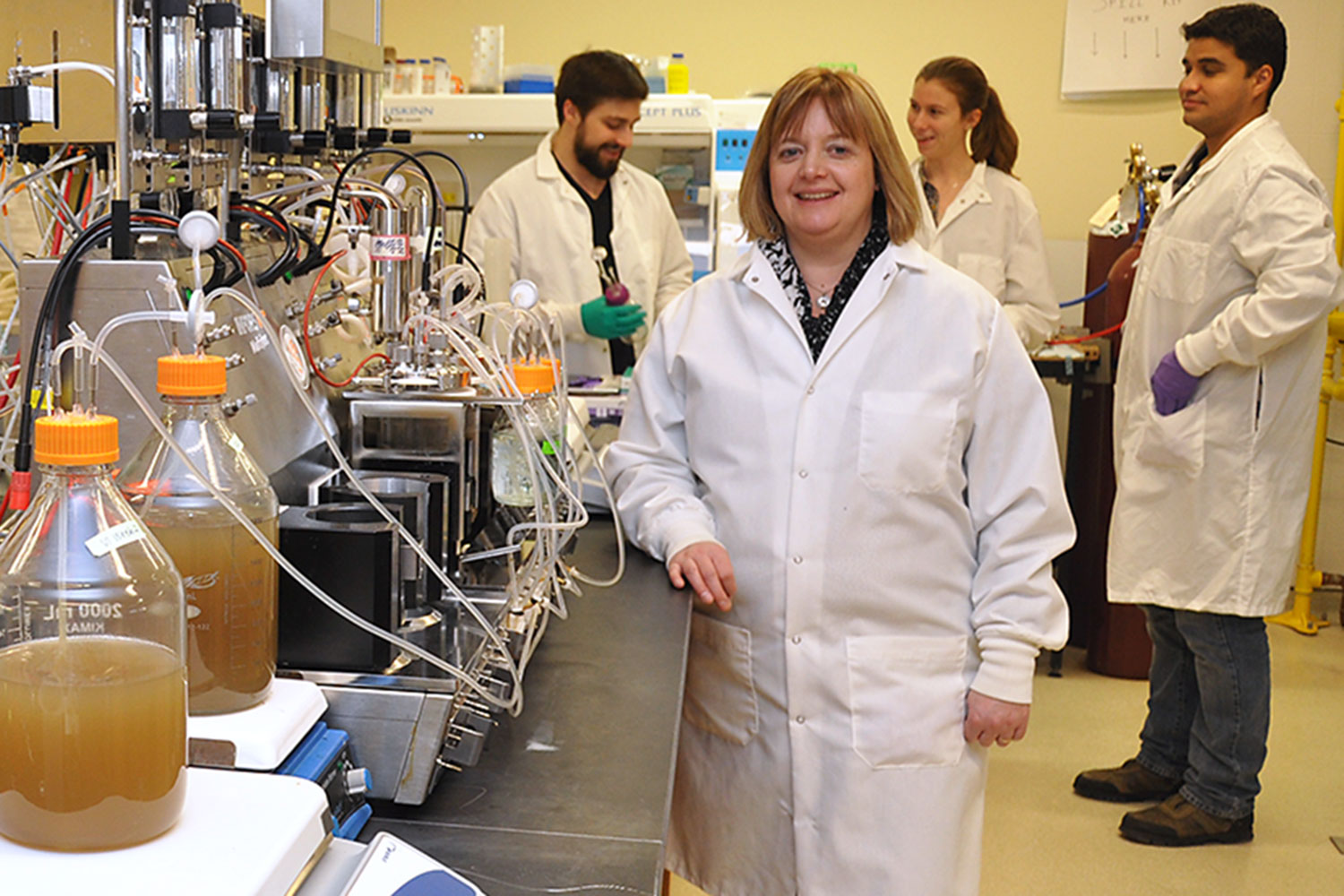

Prof. Emma Allen-Vercoe inhales deeply as she enters her lab. “It’s not too bad today,” she says of the smell, but those who have never been to her lab before would probably plug their noses at the first whiff of her research subjects: fecal microorganisms. The odour is also why her lab is located at the end of a hall in the Summerlee Science Complex.

The lab is best known for developing artificial fecal transplants for C. difficile patients, but it also works on projects that benefit animal health. One of the lab’s current projects is aimed at improving pork production.

“Antibiotics have been used as growth promoters but there is now pressure for farmers to remove antibiotics from their herds altogether,” says Allen-Vercoe. “This leaves the animals open to diseases that can be a huge problem for production.”

Antibiotics also reduce the diversity of gut microbiota, which can weaken the immune system, making pigs — and people — more susceptible to disease. Her lab is developing probiotics that could enhance the pigs’ microbial population by replacing missing bacteria that are beneficial to their immunity.

The researchers decided to study “wild” boars on a farm in Stratford, Ont., to see how their gut microbes compared to those of farmed pigs. The boars are raised as naturally as possible without the use of antibiotics or vaccines. “I was excited because of the lack of antibiotic use and the fact they’re allowed to forage in the soil as they would do in the wild,” says Allen-Vercoe. “I was looking for soil-associated microbes in pig guts.”

She sent her lab manager to collect fecal samples from the farm. “They need to be as fresh as possible because the bacteria are very sensitive,” she says.

The lab cultured the samples to make a probiotic for pigs. Only certain types of microbial species have been approved for use as food additives. The microbes the lab is growing are quite sensitive, says Allen-Vercoe, and have never been grown artificially before, so the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) hasn’t approved them as feed supplements. The lab plans to release a probiotic that meets CFIA regulations and then develop new species for approval.

“In general my lab works on human health,” she says. “We look at microbes from very healthy individuals and put them together into ecosystems to treat disease. We feel that it’s a new wave of medicine. There’s nothing like this on the market but there will be soon.” Her lab is one of several that are working on microbial-based solutions to human health problems.

Probiotics for people are currently marketed as food supplements. The lab’s primary product contains 39 strains of microbes from the human gut, which Health Canada has labeled a biologic drug. Getting it approved takes much longer than a food supplement because it must go through clinical trials to prove its safety and efficacy. “I actually think that’s a good thing because we need to do this in a very safe way,” she says.

She will discuss her research as part of the Food Forum on Gut Health, taking place on campus Feb. 18. The forum brings together experts to discuss if the gut microbiome holds the key to improving our health and productivity.

The lab is currently testing its new “microbial ecosystem therapeutic” on various types of diseases, such as C. difficile, ulcerative colitis, type 1 and type 2 diabetes, obesity, autism, depression and colorectal cancer to see how gut microbes affect disease and vice versa. “This research is all united by working on the human gut,” says Allen-Vercoe. “I can see that there’s a lot of commonality between some of these diseases whereas on the surface it may not seem that way.”