Ellen Bolte couldn’t believe what she was hearing. This past winter, the 53-year-old mom of four from suburban Chicago was making her first-ever visit to the University of Guelph. And what she was learning from researchers here sounded like hope.

It had been nearly two decades since Bolte had begun investigating possible links between gut bacteria and autism, spurred by her son’s debilitating experience with the disease.

Over the years she’d encountered plenty of skeptical doctors and scientists in the United States who refused to countenance a gut-brain connection – let alone a theory being pushed by someone lacking a formal background in either medicine or research.

Now she was at Guelph, and she was hearing something that “blew me away.”

Speaking over the phone early this summer from her home in New Lenox, Illinois, she says, “I was finally at an academic environment that was not just tolerating this possible gut-brain connection with autism but was excited about the research. I almost couldn’t wrap my head around the excitement I felt.”

In turn, her visit last February has helped to spur on Guelph projects to develop a vaccine against a potentially nasty human gastrointestinal (GI) bug and to explore possible connections between gut bacteria and autism.

Autism cases have increased almost six-fold over the past 20 years, and scientists don’t know why. Although many experts point to environmental factors, others have focused on the human gut. About 70 per cent of children with autism also have severe gastrointestinal symptoms.

Until this year, U of G chemistry professor Mario Monteiro hadn’t been thinking about autism.

He has spent five years studying Clostridium difficile, a microbe that causes GI symptoms, including diarrhea. The superbug can infect patients after antibiotics kill healthy gut bacteria.

He is working with Stellar Biotechnologies Inc. in California to develop his C. diff. vaccine that would target complex polysaccharides, or sugars, on the surface of the bug.

Monteiro’s lab has now discovered the polysaccharide target for a carbohydrate-based vaccine against another gut bug called Clostridium bolteae.

“Based on our experience with our polysaccharide C. diff. vaccine, we are confident that we can apply the same approach to create a vaccine to control diarrhea caused by C. bolteae and perhaps control autism-related symptoms,” he says.

For his studies, he used bacteria grown by Guelph microbiologist Emma Allen-Vercoe and her PhD student Mike Toh.

As a professor in Molecular and Cellular Biology, Allen-Vercoe has become an expert in culturing hard-to-grow species of bugs. This past spring, she co-authored a paper about a global project to identify and catalogue the genetic material of all microbes on and in the human body.

Allen-Vercoe says there’s more to C. bolteae than its potential role in gastrointestinal disorders. Some researchers believe toxins produced by gut bacteria, including this species, may be associated with autism symptoms. C. bolteae often shows up in higher numbers in the GI tracts of autistic children than in those of healthy kids.

She cautions that no one has yet shown that specific GI bacteria cause mental disorders, although research has shown that gut microbiota can affect mood and behaviour.

“C. bolteae is associated with autism, but this is not the same as saying that it is a cause of autism,” she says. “Much more work will be needed to show any connection. The availability of a vaccine that could be used in animal studies, for example, will greatly help us to determine the importance of C. bolteae in disease.

She says researchers need to look more closely at these microbes and links among behaviour, diet and gut health.

She is now looking for the same signature bugs in a group of autistic children.

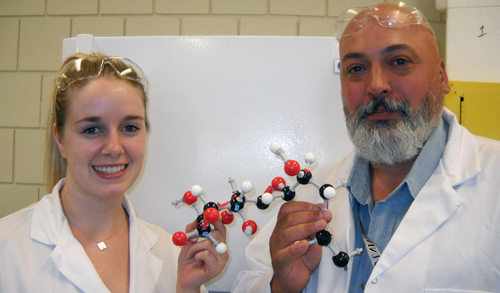

In Monteiro’s lab, master’s student Brittany Pequegnat says she’s excited about possible autism connections.

“I like the idea of improving people’s quality of life,” says Pequegnat, who studied applied pharmaceutical chemistry at Guelph for her undergrad. She hopes to pursue vaccine research that might help in fighting gastrointestinal symptoms in autistic kids.

Allen-Vercoe and Monteiro have also worked together on Desulfovibrio, another microbe associated with both gut disease and autism.

Among the proponents of the so-called “bacterial theory” of autism is Sydney Finegold, a medical researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles. Last year Allen-Vercoe attended his 90th birthday party, where she met Bolte.

By then, Bolte had worked with Finegold in an unlikely collaboration rooted in her youngest son’s experience with autism.

Andrew Bolte, now 20, was about 18 months old when he developed regressive autism, which accounts for about 25 to 30 per cent of cases of autism. Before that, he had developed normally.

For two months before developing autism, he had received numerous doses of antibiotics for recurrent ear infections. Along with the autism came severe GI symptoms.

His case spurred Bolte to investigate possible links between antibiotic-related disruptions to gut microflora and autism. A self-taught computer programmer, she had no medical or scientific training.

In 1998, she published a paper in the peer-reviewed journal Medical Hypotheses, proposing connections between regressive autism and neurotoxins produced by pathogenic Clostridium in the gut.

She has since co-authored two more papers, including one about a medical trial using oral vancomycin – an antibiotic used against gut Clostridium species – to treat autism symptoms in children, including her son. Her co-authors included Finegold and Richard Sandler, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Rush Children’s Hospital in Chicago.

In a 2003 paper, Finegold and other researchers named a new species of gut bug, Clostridium bolteae, to recognize Bolte’s insights.

Bolte had begun investigating probiotics and fecal transplants when she met Allen-Vercoe last year. The Guelph microbiologist talked about her own research interest in potential supplements and treatments to restore healthy gut bugs (http://atguelph.uoguelph.ca/2012/06/bacteria-hold-key-to-better-health/).

Recalling their conversation, Bolte says, “She started talking at Dr. Finegold’s party about what she was doing. It was everything I had dreamed of – a complex human probiotic. This is the groundbreaking research that needs to take place in order for a product like this to come to market.

Earlier this year, Bolte visited Guelph to meet with Allen-Vercoe, Monteiro and other researchers. She brought her daughter, Erin, 22, who this year completed a biochemistry degree at the University of Notre Dame.

Erin plans to become a doctor and medical researcher. Before that, she hopes to learn about microbiology as a grad student in Allen-Vercoe’s lab.

She’s applied to Guelph. But as of late June, she needed to find enough money to pay for international studies.

“I was completely blown away by how much everybody works together at Guelph,” says Erin.

Ultimately, she hopes to study the bacterial theory of autism herself. “Autism is the focus to me because I’ve grown up with it.”

Allen-Vercoe was among international scientists featured in a documentary called “The Autism Enigma,” aired last year on David Suzuki’s The Nature of Things. The show will re-air July 26 at 8 p.m. on CBC TV.