When you think of cows, you probably think of them as producers of milk, beef and leather. But there’s something else cows produce that makes them unique among the animal kingdom: they have longer antibodies than any other species. Longer antibodies are more effective at attacking bacteria and viruses, which has the potential for preventing and treating not only cattle diseases but human diseases as well.

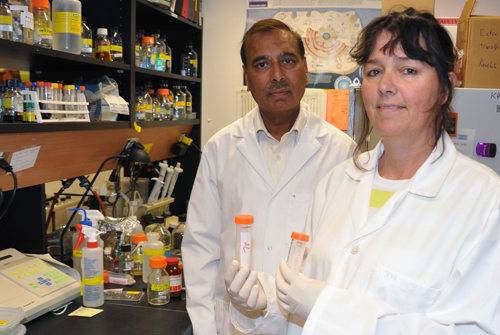

“It has great applications even for human therapeutic use,” says Prof. Azad Kaushik, an immunologist in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology. Together with PhD student Yfke Pasman, they are using cow antibodies to develop vaccines for bovine herpes virus type-1 (BoHV-1).

“This virus is a major problem in North America,” says Kaushik, adding that most Canadian cattle are exposed to the virus, costing the Canadian cattle industry up to $100 million a year. The economic impact also affects Canada’s beef and dairy trade with the European Union, where the disease has been eradicated in some countries. There are currently no vaccines that effectively protect cattle from the disease, says Kaushik.

The virus can remain dormant in the animal until it becomes stressed. By impairing the immune system, the virus makes cattle more vulnerable to other infections, such as bovine respiratory disease complex, commonly known as shipping fever.

“We engineered an antibody fragment, which we might use for therapeutic or diagnostic purposes,” says Pasman. “The fragment by itself is capable of neutralizing the virus, so it prevents attachment of the virus to the cell and subsequent replication of the virus.” In the lab, Pasman is expressing the antibody fragments in yeast cells, making it easier and cheaper to produce in large quantities.

The newly-designed antibodies to BoHV-1 would be administered through a nasal spray. Transmission of the virus often occurs during transportation when cattle are under stress. Close contact with other animals can increase stress levels and make transmission easier. The virus is often transmitted when cows lick each other’s noses or through artificial insemination, but contaminated semen could be treated with the antibody to prevent infection, says Kaushik.

He compares the interaction between antibodies and viruses to a handshake. “Through this handshake, the antibody neutralizes the virus,” he says. These antibodies, he adds, could be used to prevent and treat human afflictions like cancer, auto immune diseases and infectious diseases. “The future lies in designing these new antibodies. They would be coupled with drugs to create magic bullets to target a specific location of the body and destroy the disease-causing agent or diseased tissue.”

But more research needs to be done to determine how this handshake occurs differently in cattle. Pasman has manipulated the antibody fragment to improve its potency by increasing the number of “hands” in the handshake. More hands help the antibody latch onto the virus with a stronger handshake.

In recognition for her research, Pasman received two travel awards from the American Association of Immunologists and was invited to speak at their conference in 2010 and 2012. She also received an award from the Dairy Farmers of Ontario worth $20,000 a year for three years.