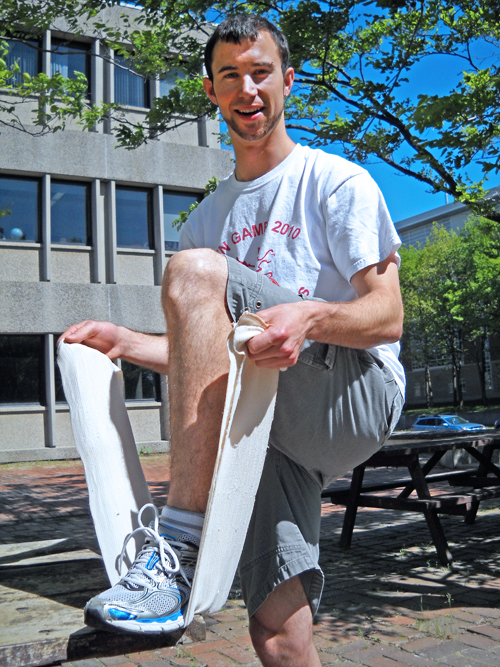

Spraining his ankle early in 2010 kept Will Mitchell off the basketball court for the rest of that winter semester. But his mishap gave him a perfect topic for his master’s thesis in human kinetics.

This summer, the graduate student in the Department of Human Health and Nutritional Sciences (HHNS) will run a study intended to learn more about ankle injuries among recreational players and athletes in varied sports.

Spraining an ankle on the field or court hardly draws as many headlines as suffering a concussion or breaking a limb. Innocuous or not, ankle injuries happen much more often to professionals and amateurs alike.

“The ankle is the most widely injured joint in sports,” says Mitchell, who began his master’s last fall after completing his undergrad here in human kinetics. “I’m sure every professional basketball player has gone through at least one ankle sprain like mine.”

That’s especially true in sports with frequent, sudden turns in direction or a lot of jumping. Think basketball, volleyball, football or soccer.

But even recreational runners – hitting roads and trails in ever-increasing numbers – may have to veer suddenly to avoid obstacles. Turn the wrong way, and you may end up hobbling into a clinic or emergency room.

According to sports medicine statistics from the United States, about 1.5 million people arrive with ankle injuries in emergency rooms every year. Marco Lozej, a chiropractor at U of G’s Health and Performance Centre (HPC), says, “It’s the most common injury in soccer and very common in sports like basketball and volleyball.”

Also a Guelph human kinetics grad, he has worked at the HPC since 2002.

This summer, Mitchell will test what happens to the ankle during sudden turns. Using special equipment in the gait biomechanics lab of his supervisor, HHNS professor Lori Vallis, he’ll collect information about forces on ankle biomechanics, muscle activity and body movement.

Vallis says abrupt cutting movements to change direction require complex limb control, including lots of sensory information from the ankle about leg position. The researchers hope to learn more about how the body’s nervous system changes after an injury, especially by delaying muscle activation to safely execute complex moves.

Mitchell will compare reactions of healthy subjects and people with previous ankle injuries to see how forces and movements change during these cutting turns. He expects to see greater variation in previously injured subjects.

He’s recruiting about 16 subjects, both male and female, ages 18 to 28.

Mitchell says his new study might help in refining return-to-play guidelines for health-care practitioners and patients. Often people recovering from injuries take up their sport or exercise regimen too soon, increasing the chances of another injury or related problem. The study might also help refine or validate treatment and rehab options.

Early last year, he wound up visiting Lozej in HPC after spraining his left ankle during a pickup basketball game in the athletics centre. “I jumped for a rebound and landed on someone’s foot, and my ankle rolled.”

Recovery involved wearing a walking cast for two weeks and rehabilitation exercises to regain range of motion and strength. By last summer, he was back to his normal mix of intramural team sports as well as squash and swimming.

Mitchell also ended up volunteering last year and this year with Lozej and other HPC practitioners. In the fall he will attend New York Chiropractic College.