Editorial bias, publication delays and prohibitive publishing costs are among a growing list of complaints levelled by researchers against the ages-old peer review process used by many scientific journals.

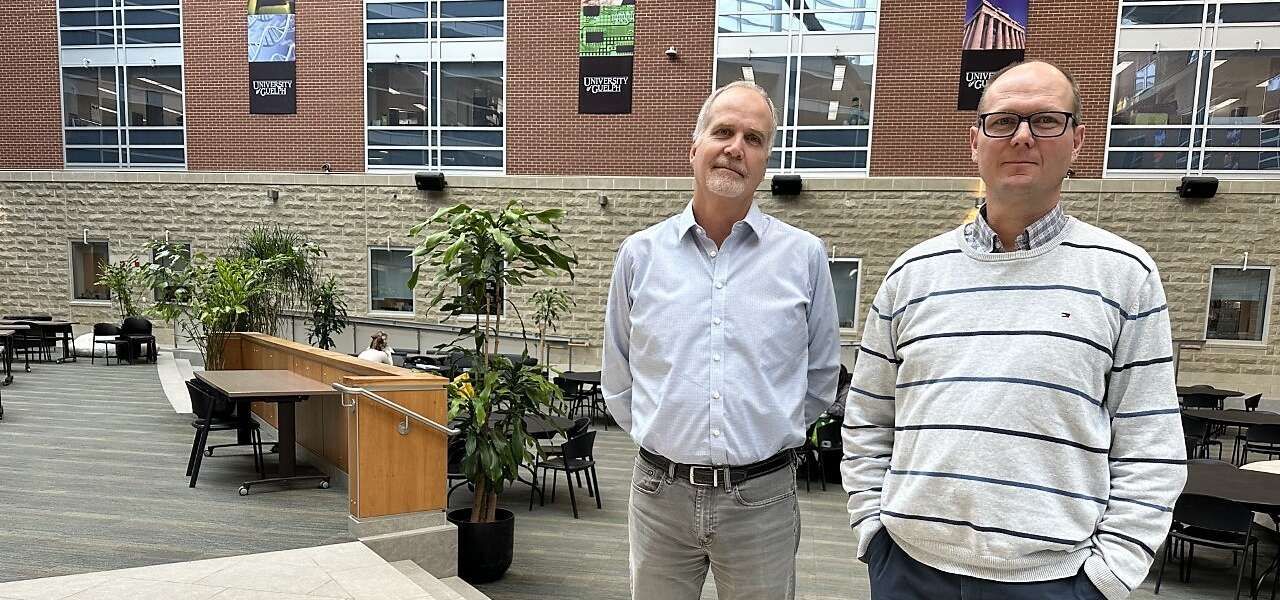

Helping authors worldwide avoid these and other problems is the goal of a new peer review service launched by University of Guelph biologists Dr. Terry Van Raay, a professor in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, and Dr. Andreas Heyland, Department of Integrative Biology, both within the College of Biological Science.

Peer Premier, incorporated as a private company in 2021, is intended to effectively separate the peer review process from journals and their publishers. The venture is the first-ever professional peer review service intended to be independent of any journal or publisher.

The service offers a new way to conduct critical peer scrutiny of papers intended for research journals while bypassing several major hurdles that the U of G researchers – and others – say have become endemic in academic publishing.

“The vast majority of scientists recognize various problems in the current publications system,” said Van Raay.

Offering lower costs and unbiased reviewer selection

By offering a faster and more transparent way to conduct this vital pre-publication step, the new venture provides an independent, double-blind review using a standardized and comprehensive rubric for assessing manuscripts, making the review more quantifiable and accessible than current practices.

Currently, journals oversee peer review – soliciting expert reviewers to vet manuscripts under consideration – as part of their overall publication process.

Getting a research article published can take as long as a year and cost thousands of dollars in fees, said Van Raay. Some big-name journals charge $10,000 or more, eating up a significant portion of scientists’ publicly funded research grants to pay for article processing charges. Those costs may also be a barrier to publishing for researchers lacking adequate funding.

The U of G duo said biased reviewer selection and the pertinent journal’s impact factor can also hinder an objective assessment of science. Reviewers typically receive no compensation for what is regarded as service work.

“But this free service has significant downsides, including lack of priority, bias in reviewing for only the high-impact-factor journals and lack of quality control. In essence, you get what you pay for,” said Van Raay.

“Appropriately compensating reviews potentially allows for a better match between manuscript and reviewers.”

Not only can the current model disadvantage individual scholars, but traditional peer review can also hinder science itself, said Heyland.

A way around ‘desk rejections’

can take as long as a year (Wikimedia / Vmenkov)

He said “desk rejections,” under which journal editors decide unilaterally whether manuscripts are worth publishing, can ultimately shape research agendas.

“All science should have the opportunity to get reviewed by appropriate reviewers in an unbiased way, and this is what we propose,” said Heyland.

Under Peer Premier, ownership of a manuscript’s review stays with the author or authors.

The author pays a fee of $1,100 to the organization. Of that, $300 goes to each of three reviewers. The remaining $200 pays for administrative costs.

Peer Premier aims to speed up the review process, with the goal of completing peer reviews within two weeks.

Reviewers are selected through an artificial intelligence algorithm. Developed in collaboration with a computer scientist, the algorithm serves as a scholarly matchmaker, picking qualified reviewers for a manuscript regardless of their institution or background. Rather than leave the process entirely to the algorithm, Heyland and Van Raay will check recommendations for reviewers.

To assess manuscripts, reviewers follow a standardized rubric also developed by the co-principals.

Authors maintain ownership of manuscripts

By holding ownership of manuscripts, researchers may use the review process to improve their paper before submission to a journal, or they might share the manuscript and review in public domain archives. Researchers can also update their manuscript with, say, additional experimental results.

“Ultimately, as a researcher, you want your paper disseminated with proper peer review and accessible to everyone,” said Van Raay. “The peer review belongs to you.”

The pair are currently testing Peer Premier.

Heyland said their venture reflects a wider push for changes to the peer review system. Many journals now make peer reviews publicly available.

One non-profit based in the United States called eLife, for instance, publishes peer-reviewed papers on its website as reviewed preprints. Authors can choose to revise manuscripts based on reviewers’ assessments; unlike other journals, eLife does not require revisions based on review comments.

Peer Premier’s founders said peer review changes effectively alter the journal publishing system.

“So, if a paper is peer reviewed and publicly available, what does it mean to be ‘published’? In a perfect world, the journal and its associated impact factor will be obsolete, the peer-reviewed paper will stand on its own merits,” Van Raay said. “That is our vision.”

The U of G biologists decided to develop their system after conversations about perceived shortcomings of conventional peer review. Van Raay and Heyland have published science papers for about 30 years.

In the process, they discussed their idea informally with colleagues. “Nobody said it was a bad idea,” said Van Raay. “They recognized the value of a standardized peer review process.”

Contact:

Dr. Andreas Heyland

aheyland@uoguelph.ca

Dr. Terry Van Raay

tvanraay@uoguelph.ca