In the battle between weeds and crops, weeds are winning. Weeds are resilient and adaptable and can damage crop yields. A new theory developed by a University of Guelph researcher suggests why. For the first time, plant scientists have shown that weeds can alter crop plant growth from a distance by affecting light signals used by the crop plants to communicate.

For the past 20 years, Dr. Clarence Swanton, a weed scientist in the Department of Plant Agriculture at the Ontario Agricultural College, has sought to answer why crop yields still decline when weeds no longer pose a threat.

Current understanding of plant competition is based on the limitation of resources of light, water and nutrients available to plants.

Swanton doesn’t dispute that aspect, but he and colleagues at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) bring something new to the table. In the presence of weeds, crop plants become so stressed out that they change their chemical and physical behaviour, the researchers write in Trends in Plant Science.

The paper introduces a new paradigm of plant competition, one that could increase crop tolerance to weeds while producing more food and reducing agriculture’s environmental footprint, and hints at the next steps needed to transform the theory into practice.

“We’ve discovered that when a plant detects a weed species, it’s asked to either grow or die. It only has a certain amount of resources it can sacrifice to defend itself,” said Swanton.

“There’s a trade-off, and that’s all new. It’s an entirely new mechanism of plant competition.”

Rapid yield loss

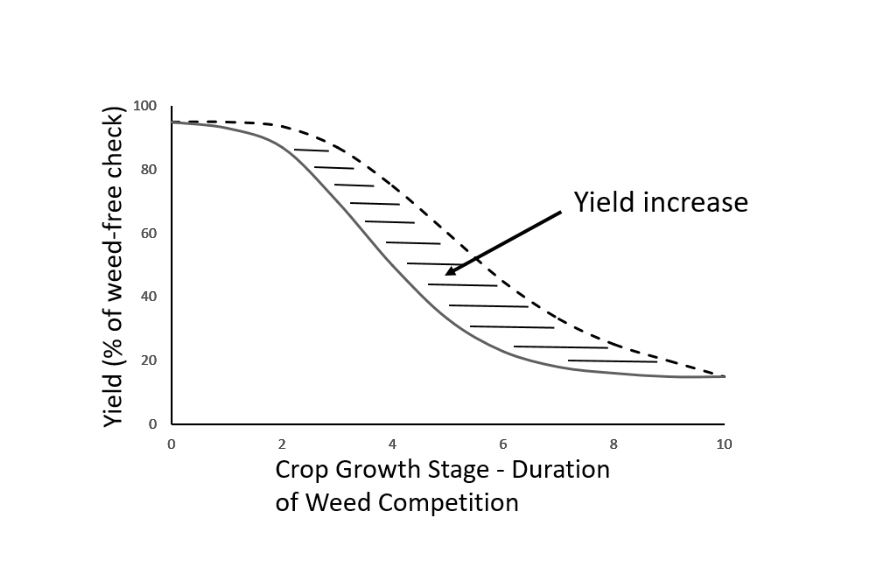

Plant scientists can chart the growth and yield of a crop in the presence of weeds.

“Early emerging weeds that are not controlled can result in a rapid loss in crop yield potential,” said Swanton.

Referring to the way in which crop plant growth is measured, he said, that in general, if weeds emerge at the first leaf stage of crop growth, yield loss can range between 10 and 20 per cent. However, if weeds emerge two or three leaf stages later, yield loss is more likely to be between three and five per cent.

“We started to develop this idea that the yield loss was actually occurring in the seedling stage, that something was changing the physiology of the plant and affecting its long-term growth,” he said.

Stressful neighbours

That something, Swanton discovered, is interference by weeds with the crop’s light signals. It can happen even before the crop emerges from the soil.

Plants depend on light to soak up vital nutrients, grow and photosynthesize. Swanton argues they also use light to communicate, a medium known as photobiology, and to detect whether they’re surrounded by siblings or competitors. Plant competition begins when crop plants detect light signals from weeds.

“We can put a corn plant in a pot and put a weed beside it, and that corn plant will detect that a neighbour is there,” said Swanton. “When the corn plant realizes its neighbour is a competitor, it’s going to change its physiology in response to that stress.”

The changes the crop makes in response to that stress harm its developmental and physiological growth, ultimately impacting its yield.

To demonstrate, Swanton referred to a PowerPoint presentation with two potted tobacco plants. The pots were concentric, with each tobacco plant growing in a central pot, ringed by an outer pot. In one case, the outer pot contained grass; the other outer pot was left empty.

“The only difference between these two plants is one is having a conversation with a neighbouring weed,” Swanton said, flipping through slides showing side-by-side images of the physiological changes to the plants over 12 to 48 hours.

At the six-day mark, the isolated tobacco plant was thriving. The other was dead.

“That’s six days,” Swanton said. “Nobody touched this plant. This is the first time in the biological world that we have evidence of one plant having the ability to kill another.”

Change the signals, increase the yield

To mitigate yield loss, Swanton and his colleagues are investigating ways to stop crop plants from responding to the signals from weeds altogether. If the crop plant’s light signals and other physiological aspects are altered, said Swanton, it may become more tolerant to weeds, stemming yield loss.

By understanding these new mechanisms of plant competition, the researchers hope to provide plant breeders with new knowledge on plant competition, which may also allow for the development of crop plants that are more tolerant to weeds.

The possibilities are endless, added Swanton. “You’d have greater diversity in the cropping system, better control of erosion, perhaps better nutrient supply, or ways to reduce the environmental footprint of agriculture.”

But further research is needed, he said, specifically on the genetic and molecular level to properly understand the light signals.

And the research presents some challenges of its own, said Swanton: “Can you achieve that tolerance without altering other things that make the plant more susceptible to something else?”

This research was funded by Food from Thought at the University of Guelph.

Contact:

Dr. Clarence Swanton

cswanton@uoguelph.ca