A University of Guelph researcher’s photograph of the moment freshwater snail embryos first see the world is a finalist in Science Exposed, a photography contest organized by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Rebecca Osborne, a U of G environmental science and toxicology doctoral candidate supervised by Dr. Ryan Prosser in the Ontario Agricultural College, studies the multi-generational effects of pollution on freshwater ecosystems. She works with the eggs of freshwater snails, a sentinel species that provides an early warning of the effects an environmental contaminant can have on a waterway.

Her photograph of snail embryos is now vying for one of three juried prizes as well as the People’s Choice Award, which the public can vote for between now and Sept. 18.

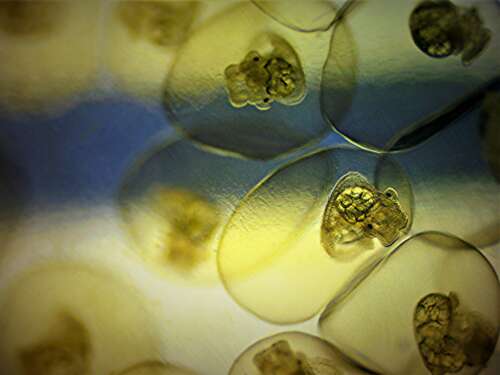

The photograph captures the moment when the embryos’ eyespots and eyestalks first appear. These tentacles allow snails to perceive light, pressure and chemical signals.

“One day you go into the lab, and the embryos have no eyes,” Osborne said. “The next day, they can see — it’s a significant and exciting moment in their development. That’s the moment I wanted to share.”

Photo used time-lapse macrophotography

Contaminants can affect an embryo’s ability to develop enough to hatch, she explained. She compares the hatching success of healthy control eggs, such as those in the photograph, to eggs laid by snails previously exposed to high levels of chemicals.

A mass of snail eggs measures only seven to eight millimetres across. Osborne started using time-lapse macrophotography out of curiosity, to provide a close-up view of snail egg development that she couldn’t see with the naked eye.

Photography has since become a tool she uses to map developmental milestones in healthy embryos and to track when and how contaminants interrupt normal development. When a generation is exposed, the offspring of subsequent generations are much more vulnerable to pollutants, she said.

“While existing guidelines about contaminants are protective, they are based on lethality,” she added. “Photography can give a more sensitive measure of how pollution impacts living organisms across generations, helping us to nuance policy recommendations for environmental health.”

About ‘Science Exposed’

Science Exposed showcases images of Canadian research in all fields of study but the arts. The contest promotes images as effective — and sometimes beautiful, emotional, or surprising — ways of sharing research knowledge and fostering curiosity about it.

Entries are judged on both the quality of the photograph and the clarity of text that explains the image and the research.

A jury will select three winners from among the 20 Science Exposed finalists, while the public will determine the winner of the People’s Choice Award. Each prize is worth $2,000.