This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

By Dr. Louise Grogan, Department of Economics and Finance

The lack of food security in Afghanistan may soon become a threat to the stability of many other countries.

Without a radical change of western policy towards the Taliban, millions of people will make their way to anywhere they can find food. The arrival of the poorest of the poor in neighbouring countries and the European Union threatens to fuel further political polarization at a moment in which many governments are already under severe strain.

Domestic tax and benefits scandals, Brexit, yo-yo COVID-19 policies and failure to deter migrants from crossing the English Channel have already eroded trust in British and European politicians.

Both accepting and rejecting refugees may be very costly in these countries, economically and politically.

Meanwhile in Afghanistan, the Taliban remain in power. Even in the absence of a moral motive to alleviate famine, there is a strong rationale for the West to do whatever it takes to feed Afghanistan this winter.

Women have been the focus

For 20 years, the fight against the Taliban has been framed as a fight against the Taliban has been framed in NATO countries as a fight for women’s rights.

This is similar to how post-revolution fighting in central Asia in the 1920s was portrayed, and the 1980s occupation of Afghanistan by the Soviets.

As a child, young Sharbat Gula became the face of Soviet-occupied Afghanistan to citizens of the West. Her famed 1985 appearance on the cover of National Geographic magazine preceded by a year the American sale of Stinger missiles to the Mujahadeen, forerunners of the Taliban.

Other well-known photos taken in Afghanistan featured mini-skirted girls walking in 1970s Kabul before the Soviet invasion, women in burkas under the Taliban and various photos of girls in hijab attending school under the governments of Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani. Together these photos suggested dramatic swings in the status of Afghan women that coincided with changes in government.

There were real improvements during the 20 years of western presence in Afghanistan before the U.S. withdrawal in August 2021. More rural children, and more girls, went to school. Infant and maternal mortality rates fell. Still, improvements in living standards of rural populations aren’t sustainable if there’s no food security.

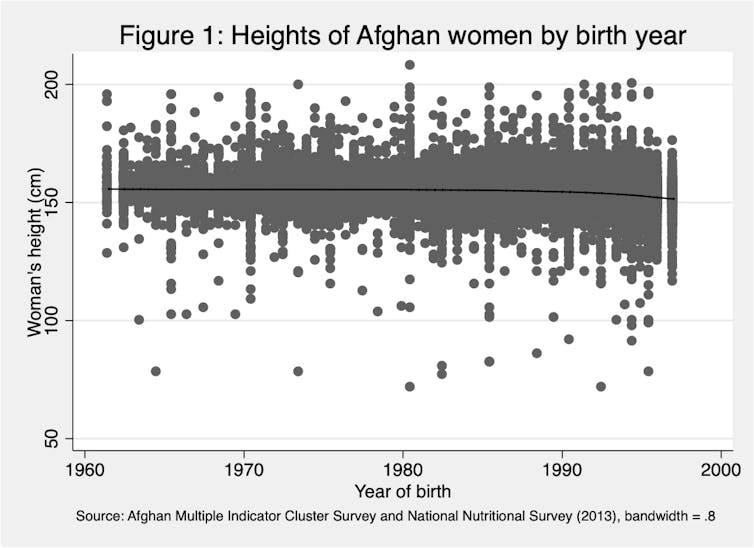

For women, height at the age of 15 is a summary measure of the nutrition and disease environment during childhood. National survey data from 2013 shows that women born before 1976 in the part of the historic province of Badakhshan — incorporated into the Soviet Union — were three to four centimetres taller than those in Afghan Badakhshan.

By this measure, there has been no real progress in food security during the childhoods of young Afghan women.

It’s much easier to count the number of schools and hospitals built, the number of female students or how many women presenters appear on television than it is to reliably measure the amount of food being consumed. Indeed, the failure to alleviate food insecurity during the NATO campaign may have been a harbinger for the Taliban’s ultimate victory.

Food is the No. 1 need

More hospitals and better highways also don’t do much to help people if they’re still hungry. Afghans have long needed a strong foundation of food and physical security, and still do. Past Soviet successes in education and increasing the status of women in Central Asia were founded on providing people with food to eat.

Geography may not help domestic food security in Central Asia. In Tajikistan, which shares a common border, language (Dari) and culture with northern Afghanistan, the main income source of families is remittances from family members working in Russia. But seasonal migration to Russia isn’t an option for Afghan families.

Data also show that women in Afghanistan had far more difficult lives, even 15 years after the NATO intervention, than women in neighbouring countries. Afghan women still marry far earlier, have more children and are much more accepting of spousal violence than are those in neighbouring Tajikistan.

News reports from Afghanistan are increasingly focused on food shortages. There is widespread recognition that millions could starve this winter without massive food aid.

American aid may have been the main factor averting famine in recent years, when lack of rain and lack of security constrained the harvesting of food crops.

Amid dismay in NATO countries about the rapid collapse of the Afghan army in August 2021, and the US$2 trillion cost of the failed war, there’s been little evidence of any consensus among NATO allies about what to do. More than three months after the Taliban takeover, U.S.-held Afghan government funds remain frozen. There is no NATO or EU representation in the country.

Many more Sharbat Gulas

Iris-recognition software allowed the West to rediscover Sharbat Gula, of National Geographic fame, after her child marriage and the bearing of five children. In response to international news reports about her legal woes in Pakistan in 2017, former president Ghani offered her a large house in Kabul.

But there are millions more like her — and their husbands and children — who cannot be welcomed elsewhere.

NATO countries should deal urgently and co-operatively with the Taliban. If they don’t, nations ranging from China to the United Kingdom face the spectre of hundreds of thousands of destitute refugees at their borders.

The domestic political implications for these countries, including fuelling support for anti-immigration, anti-EU parties, should not be underestimated.

The only answer is to make life in Afghanistan slightly less difficult by facilitating the large-scale import of food this winter. That means accepting the reality of Taliban rule, immediately unblocking at least some of the international accounts frozen since August 2021 and financing humanitarian aid. The rest will have to wait.