This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Although international trade has long been affected by domestic politics, former U.S. president Donald Trump dramatically increased trade irritants between the United States and Canada. This was especially challenging in the agricultural sector where political interference in international trade is more prevalent than in the non-agricultural sector.

In our recent article in the Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics, we analyzed how Trump’s presidency affected agri-food trade between the two countries and how the situation might change under President Joe Biden.

We argue that Trump’s negative rhetoric and actions heightened trade uncertainty and undermined global trading rules, which tends to disrupt international trade. This was a major challenge for a small open economy like Canada that depends largely on the American market. In particular, the politically sensitive nature of the agri-food sector makes agricultural trade highly dependent on diplomatic ties between countries.

Canada more reliant on the U.S.

Canada’s relationship with the U.S. is important for the agri-food sector in both countries, but it’s somewhat one-sided in terms of Canadian reliance on the American market.

Canada is the top destination for American agricultural exports, accounting for 15 per cent of the country’s total agricultural exports in 2019. Conversely, the U.S. is the foremost buyer of Canadian agri-food products, accounting for 58 per cent of total Canadian agri-food exports. This isn’t surprising due to the countries’ close proximity and similar consumer tastes and values.

But the Canada-U.S. political relationship became hostile during the Trump presidency due to the former president’s erratic foreign policy decisions, tariff wars and his verbal attacks on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. The tense political relationship created an environment of uncertainty, adversely affecting the bilateral trading relationship.

Major trade disputes between the two countries at both the World Trade Organization (WTO) and within the former North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) have largely involved the agricultural sector. WTO trade disputes over softwood lumber, hard wheat and durum and the compulsory country-of-origin labelling requirements, for example, were all within the agricultural sector.

The long-standing softwood lumber dispute predates Trump, but was escalated during his presidency and could not be sorted out under NAFTA and WTO dispute settlement mechanisms. It was resolved only through political negotiations when both parties signed a memorandum of understanding.

Canada diversifying?

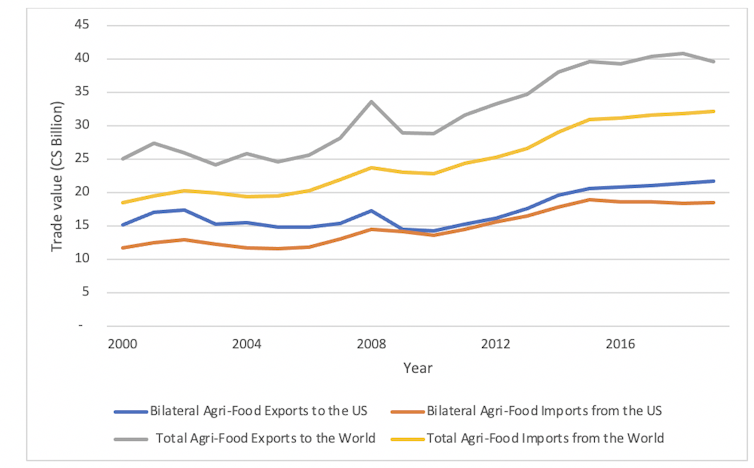

The graph below shows that although bilateral agri-food exports from Canada to the U.S. increased marginally from 2015 and 2019, Canadian agri-food imports from the U.S. remained flat.

The increasing number of agri-food imports to Canada from nations other than the U.S., and the flat-lining of imports from south of the border, shows the Canadian economy may be diversifying away from the U.S. and not relying solely on Americans to be the main suppliers of its food basket.

Continuing trade uncertainty with the U.S. could push Canada to pursue its market diversification agenda more aggressively. Canada has shown serious signs of market diversification through its membership in two major free-trade agreements — the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with the European Union and the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) with Pacific Rim countries.

Biden’s presidency

In his inaugural speech, Biden promised to immediately work to repair and renew relationships with U.S. allies and return America to a leadership role in the world. His first call to a foreign leader was made to Trudeau, and he assured the prime minister that “Buy American” policies weren’t aimed at Canada.

Biden is facing significant domestic political challenges, and it’s too soon to know how he’ll deal with trade irritants and address the harm done by the Trump administration. But it’s clear he’s intent on returning to multilateralism.

The American dissatisfaction with the World Trade Organization (WTO) predates Trump and runs deep in the U.S. Barack Obama’s administration also blocked appointments to the appellate body based on this dissatisfaction. However, Biden has been clear about supporting a strong multilateral trading system and isn’t expected to be obstructionist like the Trump administration, but instead will likely work with allies to address concerns with the WTO.

When it comes to trade deals, Biden has acknowledged the importance of deals like the CPTPP that Trump pulled out of on his third day in office. But he’s also promised to protect American workers.

Protectionist forces

Protectionist forces will continue to disrupt trade between the two countries, but we can expect a closer and more constructive relationship under Biden. Trade disputes won’t disappear, but the approach to them will change, and improved U.S.-Canada diplomatic relations will have a positive impact on Canada’s agri-food sector.

Canada’s prime minister and Biden are much closer in terms of ideology, policy objectives and leadership style than Trump and Trudeau were, and they share views on eliminating trade barriers instead of imposing them.

The past four years of trade tensions between the U.S. and Canada were largely politically motivated, especially Trump’s imposition of steel and aluminium tariffs in the name of national security, which Canada responded to by imposing retaliatory tariffs on a number of agri-food products from the United States.

Such unilateral decisions will probably be minimal under Biden. Bilateral trade flows between both countries are unlikely to be affected by the types of erratic trade actions favoured by Trump.

Closer political ties between the Biden administration and the Canadian prime minister means a more constructive and co-operative approach to solving challenges between the two countries in the agri-food sector. Trade disputes will undoubtedly continue, but diplomatic efforts will work to resolve these disputes. This is a positive development for the Canadian agri-food industry.

By Dr. Sylvanus Kwaku Afesorgbor, professor of agri-food trade and policy, University of Guelph; and Prof. Eugene Beaulieu, economics, University of Calgary