This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, decision-makers around the world have grappled with the question of whether to reopen counties and cities all at the same time or allow less affected places to reopen first. Our research suggests that with sufficient testing and co-ordination, reopening schools and businesses in areas of Ontario without active outbreaks can be as effective as a lengthy provincewide lockdown in minimizing total infections while also reducing closures.

It may surprise many readers that we came at this project from the study of climate change negotiations and underwater giant kelp forests.

Inspired by this, we asked whether local activism or global negotiations form the fastest path to reducing greenhouse gas emissions worldwide. The answer turned out to lie in between: switch from regional climate coalitions to enforceable global agreements once several — but not yet all — regions commit to reducing emissions. We found the same principle applied when the spring COVID-19 outbreak began to recede in Ontario and launched debates over reopening.Famously, lush kelp stands can be rapidly grazed down into rocky barrens by sea urchins — animals little more than spine-covered balls with a mouth. Yet we found that collective urchin behaviour is all-important: sometimes urchins stay close to their shelters and maintain only small barren patches, while at other times urchins swarm and quickly bulldoze kelp forests into barrens over large swaths of the coastline.

Some argued that areas with lower case counts should be allowed to open sooner, while others argued that a patchwork of opened and closed areas would only cause individuals to travel from closed areas to open areas in order to access services, thereby spreading the virus to areas that had it more under control.

Further, travellers could spread the virus out from large cities, which were hotspots of travel and COVID-19 cases. Therefore, we decided to tackle this question with a mathematical model that is not unlike the models we use to study kelp forests and climate change, all of which are concerned with populations distributed across patches.

This kind of accidental insight, where researchers working on one problem can see applications of their methods or concepts in some other apparently unconnected area, happens all the time in the mathematical sciences. And perhaps it is not so accidental, after all, because mathematical modelling can provide a unifying framework to discover commonalities in apparently different systems.

What we found

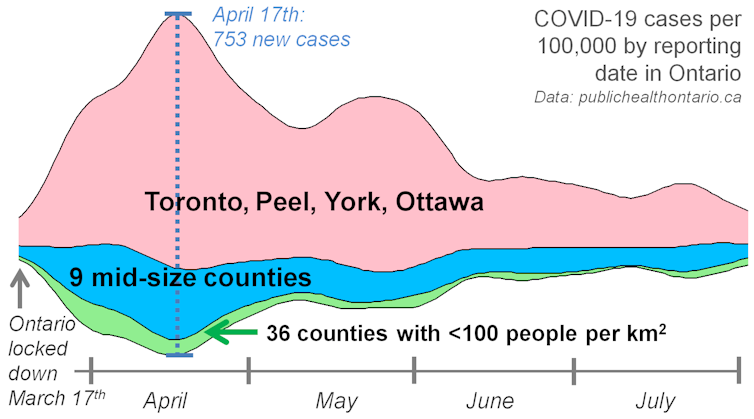

Our study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences used actual commuting patterns to account for daily travel among census divisions and modelled county-to-county differences in travel and in COVID-19 transmission, the presence of symptoms and recovery time. We also used daily case counts for each public health unit to estimate how COVID-19 transmission rate increases in more densely populated areas. These data show that in Ontario’s four largest urban areas COVID-19 spreads quickly, is hard to eliminate and is 250 per cent more prevalent compared to the province overall.

But in many less-populated counties, we found that outbreaks are less intense and subside faster once schools and workplaces close. By closing on an as-needed basis when local cases begin to spike, municipalities in our model stay on top of the epidemic and cases imported by travellers — even when we doubled rates of travel from previous years.

Accordingly, the local strategy also affords flexibility to prolong closures in areas with continuing active outbreaks — primarily more populous counties with higher epidemic spread rates — without keeping the rest of the province in lockdown.

Act fast and act locally, co-ordinate globally

For this local approach to work, however, sufficient testing capacity and fast test turnaround times are needed to catch local outbreaks in time. In addition, acting decisively by closing schools and workplaces as soon as detected cases per 100,000 exceed a critical threshold reduces the total number of days in lockdown. These two things were difficult to achieve in Canada early in the epidemic (March-May), and hence a province-wide lockdown was the best approach at that time.

These results don’t mean that individual counties can go it alone. In the United States, we have seen how poor federal co-ordination led to very late closures or premature reopenings in some states, which then became a source of COVID-19 cases country-wide.

Accordingly, within Ontario, our model shows that county-by-county closures are most beneficial when testing and closing/reopening criteria are co-ordinated by the province. Otherwise, travellers from counties that open prematurely spread cases to opened areas, forcing them to re-enter lockdown.

What about re-closing?

COVID-19 cases have been rising steadily since summer 2020. The trend will likely accelerate exponentially now that schools have reopened and temperatures are dropping, causing people to spend more time indoors.

Our model projections for the current phase show that local re-closing of counties and cities will continue to work better than a province-wide closure, subject to our provisos on co-ordinating and fast testing. As we enter the fall and winter, greater testing capacity, prompt action and a flexible county-by-county approach will continue to be the keys to reducing the economic and social impacts of the pandemic while minimizing COVID-19 infection.

Vadim Karatayev, postdoctoral fellow, School of Environmental Sciences; Prof. Madhur Anand, SES, and director of Global Ecological Change & Sustainability Laboratory; Prof. Chris Bauch, Applied Mathematics, University of Waterloo