This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

The upcoming election in Spain will be different.

While the country has long been one of the few in western Europe without a populist anti-immigrant party, the legislative elections on April 28 will likely change that.

Vox, a party that looks very similar to the French Front National and the Austrian Freedom Party, will, according to current polls, garner about 10 per cent of the vote and rake up a sizeable number of seats in parliament.

If the experience in other countries offers any indication, that means anti-immigrant rhetoric will likely become a staple of Spanish politics in the indefinite future.

Vox was initially founded as a nationalist party opposing separatism and decentralization. Recently, however, it has become more vocal in criticizing immigration, multiculturalism, the European Union and Islam.

In its party manifesto, it advocates the deportation of undocumented and criminal migrants, restrictions in naturalization policies, a selective and arguably discriminatory admission process favouring immigrants from “friendly” countries and restrictions on the public expression of Islam.

Political scientists long predicted that this type of party could not gain a foothold in Spain. Because decentralization is a more central concern than immigration, and the mainstream right-of-centre party (the Partido Popular) already takes a restrictive position on immigration, so the argument goes, there is no place for an anti-immigrant party in Spain.

Why this election will be different

While this type of reasoning describes Spanish politics well in normal times, it does not today. With highly volatile election results in recent years (in 2015, the net change in seats amounted to more than 70 per cent) and an ongoing constitutional crisis regarding the status of Catalonia within the Spanish state, politics are marked by uncertainty.

After having climbed out of the economic abyss of the 2008 financial crisis, the Spanish economy has been in recession since 2015, and the aftermath of the Syrian refugee crisis has seen the annual intake of asylum-seekers in Spain skyrocket from less than 6,000 in 2014 to more than 30,000 in 2017.

In addition to all this economic and social turbulence, the current partisan context lends itself very well to the populist argument that there is a politically correct and self-serving elite that does not care about the concerns of “the people.”

The Partido Popular, usually the most obvious choice for a voter who opposes immigration, is embroiled in a massive corruption scandal that has been estimated to involve a loss of at least 120 million euros (about $180 million Canadian dollars) to the public treasury. Indeed, the very reason an election is taking place is that the scandal forced former prime minister Mariano Rajoy to resign.

The interim prime minister, social democrat Pedro Sánchez, is an anti-populist, pro-EU intellectual who tends to invoke humanitarian considerations rather than majority opinion when describing his views on immigration, and who has repeatedly offered a safe haven to migrant ships that were denied in other European countries.

In research that is currently under review, I demonstrate that most anti-immigrant parties in western Europe had their first electoral success under these kinds of unusual circumstances, but that they did not disappear once politics normalized afterwards.

When these parties break through, they are able to lock up a spot in the party system, gain credibility as a realistic political player, draw more attention to the issue of immigration and obtain the necessary resources to build their party organization. These are exactly the kinds of factors that previous research has shown to be crucial to anti-immigrant parties’ success.

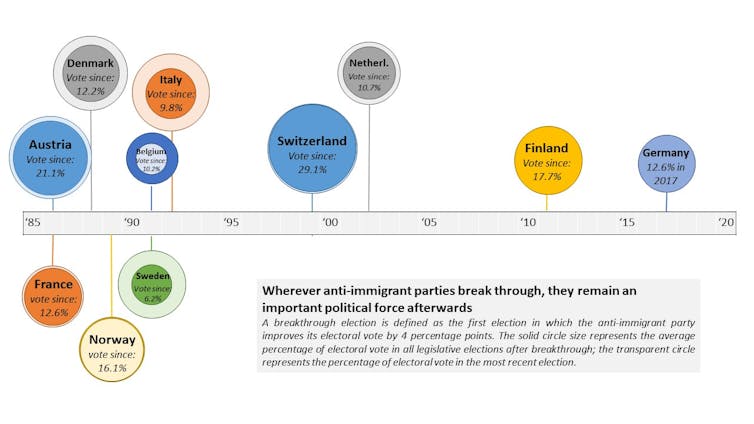

The following figure illustrates this pattern:

Because their electoral breakthrough depends on an unusual set of circumstances, the timing of anti-immigrant parties’ arrival has been quite different from one western European country to the next.

But once that unusual election occurs, anti-immigrant parties tend to stick around. In all countries, anti-immigrant parties have had considerable success after breaking through, and only in Belgium do we see a recent decline in their electoral fortunes.

It would be a grave mistake to assume these parties are inconsequential: across western Europe, they have affected public policy, incentivized mainstream parties to take a harsher stance on immigration and made anti-immigrant sentiment more politically consequential.

The election in Spain, therefore, is not only important because it changes the political landscape for the next legislative term. The success of Vox will likely secure a place for anti-immigrant parties in the Spanish party system for the indefinite future, with important implications for the future of immigration politics in the country.

(Prof. Koning was featured on the April 26 episode of CBC Radio’s Day 6, speaking of Spain’s far-right political shift. An excerpt of his interview appears on the program’s website).